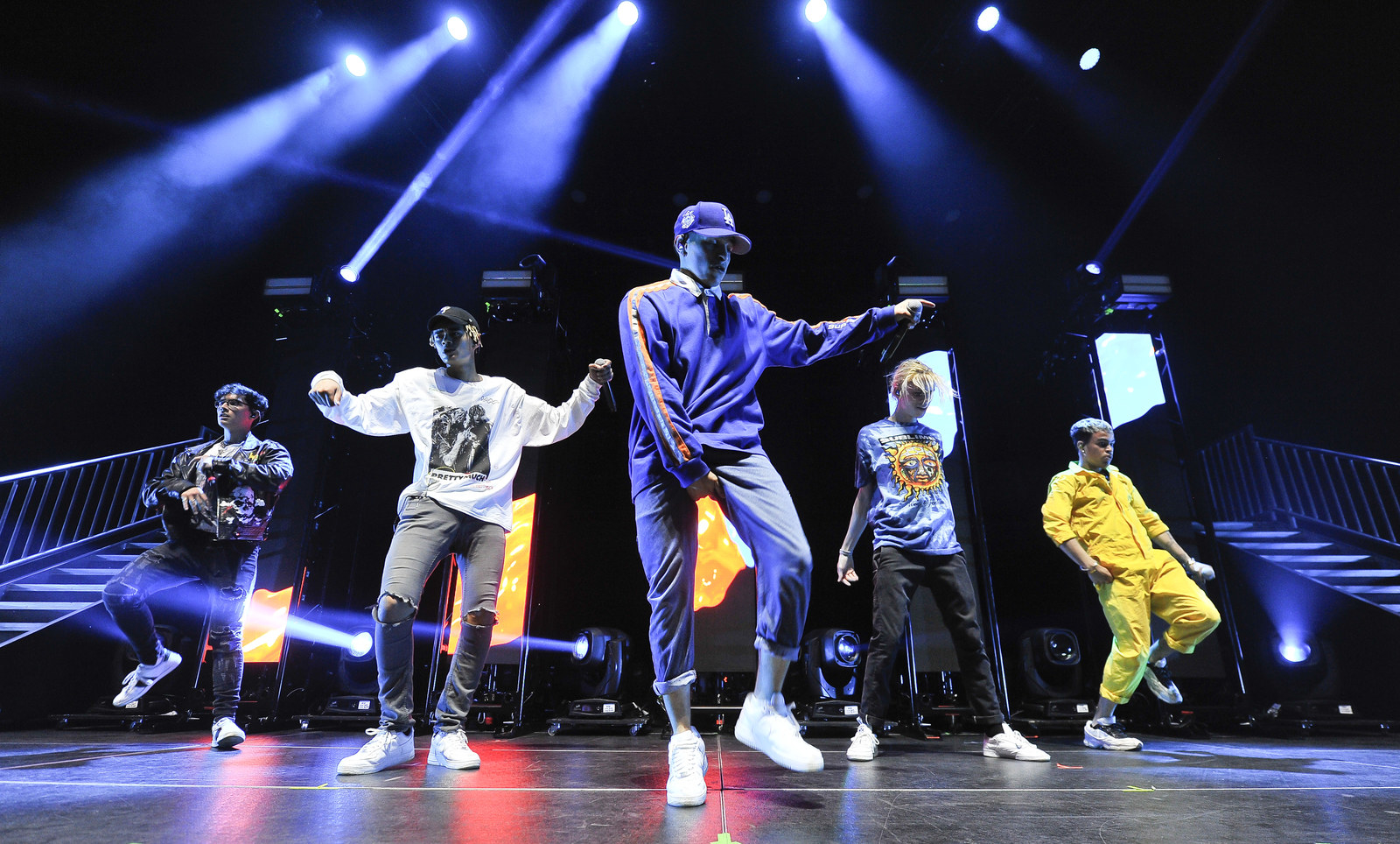

On an overcast, drizzly morning in March, five stylish boys and a man in a swole Tony the Tiger costume draw stares in Manhattan’s Union Square Park, across from Kellogg’s NYC cafe. The boys’ names are Zion Kuwonu, Nick Mara, Edwin Honoret, Brandon Arreaga, and Austin Porter, and together they are PrettyMuch, one of Simon Cowell’s newest music projects, and — it probably goes without saying — very, very cute. A photographer kneels before them as they mug for the camera, posing with a cereal box and a “vinyl” record made out of chocolate cereal.

The scene is bizarre, almost hallucinogenic, especially to commuters on their way to work. A curious passerby asks, “Who are you?”

Without missing a beat, they exclaim: “We’re a boy band!”

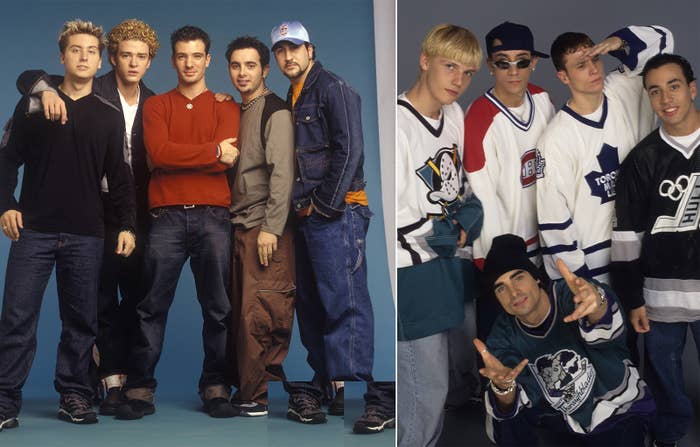

Not too long ago, a group of male singers would’ve been loath to identify themselves this way. Despite being voted the best boy band of all time, the Backstreet Boys denied being one for years (though they later came around) because the term was considered “very derogatory” and they wanted to be taken seriously as a vocal group. In a bid to seem more artistically legit, Aussie act 5 Seconds of Summer maintain they’re a rock band, not a boy band, though many media outlets think the punk-lite brochachos doth protest too much. Meanwhile, other groups have tried to distance themselves from the moniker and its forefathers. In a 2013 interview with Glamour, Zayn Malik suggested One Direction’s refusal to dance was their way of bucking the boy-band formula. Meanwhile, the Wanted, another group of that era, playfully mocked their pop predecessors (Backstreet Boys and NSYNC) in a 2013 music video.

But instead of balking at the boy-band label, PrettyMuch has reclaimed it. And they’re not the only ones. Brockhampton, a fellow California-based group, has also proudly claimed the moniker (even starring in a Viceland documentary series called American Boyband), while independently releasing a dizzying array of infectiously sweet pop songs, emotional ballads, frenzied bangers, and more. But outlets stubbornly deem the 14-person collective — made of rappers, singers, producers, and other creatives — a hip-hop or rap group, to their annoyance. “We’re just a boy band,” Ameer Vann, one of the group’s songwriters and rappers, told the Yellow Wall in January. “People tack other shit onto it like ‘self-proclaimed’ and ‘internet’ and that’s bullshit. You’re robbing me. Let me be Zayn, what the fuck.”

Overseas, bands have had no problem embracing the label: The K-pop world has long been taking the American boy-band formula and consistently blowing it up beyond imagination. Meanwhile, Fanxyred (until recently, FFC-Acrush) is a Chinese girl group touted by media outlets as an “all-girl boy band” thanks to its androgynous styling and crotch-grabbing choreography. (For the record, the band prefers using genderless terms — meishaonian, meaning handsome youths — but its fans refer to the group as lao gang, which translates to “husbands.”)

So why are American groups adopting the title now? “Boy bands, I feel matter, because, one, going back to the Beatles. It's just such an iconic thing and girls love it,” PrettyMuch’s Brandon explains to me with an ever-ready grin during their appearance in Union Square. “What's better than a girl falling in love with one guy is a girl falling in love with five guys. It's just better. You get to fall in love with each individual personality and see what each one of us brings to the table and it's cool, ‘cause on our side, we can rely on each other to carry each other’s weight.”

Meanwhile, Brockhampton not only embraces the boy-band label, but uses it tactically. “You can only get so far as a rap collective,” Ameer told radio documentary show Yours Truly. “Just by putting the name ‘rap’ on yourself, you’ve set a limit. But a pop star can do anything.” (It turns out not exactly anything; the 21-year-old rapper was recently accused by multiple women on Twitter of being emotionally abusive and having sex with a minor. He later tweeted that he had “disrespected” and cheated on past partners, but denied any criminal misconduct).

Historically, of course, there have been pretty strict limits set on who's anointed as a pop star and who gets to be in a boy band. The boy bands with the most massive success have been highly curated through the help of scouts, auditions, and even reality shows. This kind of curation has inevitably led to boy bands having trademark qualities — youth, attractiveness, and cheesy charm — but also looking and behaving a certain way. And that’s why groups like PrettyMuch and Brockhampton might just be the perfect inheritors of the boy-band title; they’re simultaneously embracing the label and expanding the potential for what it can mean.

“You know what’s really funny? A lot of times when people ask me what I do and I say I’m in a boy band, they ask me what instruments we play first,” says Austin of PrettyMuch, sandwiched between his bandmates on an umber-colored couch. “They don’t get the immediate concept of, like, we’re like NSYNC and Backstreet Boys kinda, where we dance, everything like that.”

Austin’s referencing what we can call the boy-band blueprint — which is helpful to review. Take three or more fresh-faced guys — five’s been the magic number — in their teens or twenties. Each fits a “type” (parodic MTV group 2Gether defined theirs as: the cute one, shy one, heartthrob, bad boy, and the older brother), so fans can pick and swoon over faves. The boys sing vulnerably about how their love is all they have to give with sprinkles of innuendo (“Gonna make you come tonight / Over to my house”) and bizarre references (“Like Doctor Zhivago / All my love I’ll be sending”). These songs serenade a nameless “girl” or “baby” (and sometimes even a “baby girl”), while the boys wear pained, pleading expressions.

Do they dance? Sometimes, especially if it involves body rolls, pelvic thrusts, and anything that a preteen imagines sex might look like. (Rolling Stone once called a New Kids on the Block tour “one of the most sexually charged shows on the road, a happy marriage of the Chi-Lites and the Chippendale dancers.”) And, if you look closely, a music Svengali or mastermind like Lou Pearlman typically lurks behind the scenes — a phantom of the pop-era — helping the group become as marketable as possible.

For fans, boy bands become a puberty-themed playground for expression, fantasy, and desire. Their youthfulness feels nonthreatening — especially compared to adult solo artists — and earnest. (In the early NKOTB track, “I Wanna Be Loved by You,” a prepubescent Joey McIntyre croons, “I might be young, but I’m not too young to let you know how I feel / I’m Joe, and I’m a Capricorn.” These guys are open books.) A means for one-sided exploration and self-discovery, boy bands are a step up from imaginary boyfriends since they, well, exist, and dating them is highly unlikely, but still sort of possible.

And then there are the lyrics. Their words routinely reassure girls of their worth and desirability as they are: NSYNC cooed about how “God must have spent a little more time on you”; Backstreet Boys claimed “what makes you different makes you beautiful”; and O-Town sang an anthem for shy girls. For teens, it’s a welcome respite from the unattainable perfection permeating media, magazines, and, more recently, Instagram feeds.

A final element in the long history of boy bands is their tendency to be very, very white. Which is why PrettyMuch is kind of revolutionary; between the five of them, there’s West African, Dominican, Mexican, Italian, Irish, and Scottish blood. They might not look like other boy bands, but they induce that familiar giddy, fun feeling. Similarly, their music (like boy bands in general) can be a nostalgia trap while still feeling modern.

PrettyMuch’s first single, “Would You Mind,” sounds like a sleeker New Kids on the Block hit through its retro-feeling swing beats, while two of their other songs — “10,000 Hours” and “Open Arms” — pay homage to '90s R&B quartet Shai by lifting their tapestry of harmonies, boosting their appeal to both teen and adult listeners. And what’s more, PrettyMuch’s diversity brings an authenticity to their different music styles, instead of aping them like previous groups sometimes did. “It’s nice, now we have more to bring to the table,” says Edwin, who’s Dominican and the group’s most fashion-adventurous trendsetter. “We can do Latin-flavored songs because I come from a background like that.”

It feels like a necessary and obvious progression to make in the boy-band world. But it might actually be more of a resurrection: The origins of modern boy bands had more color to them than most people remember.

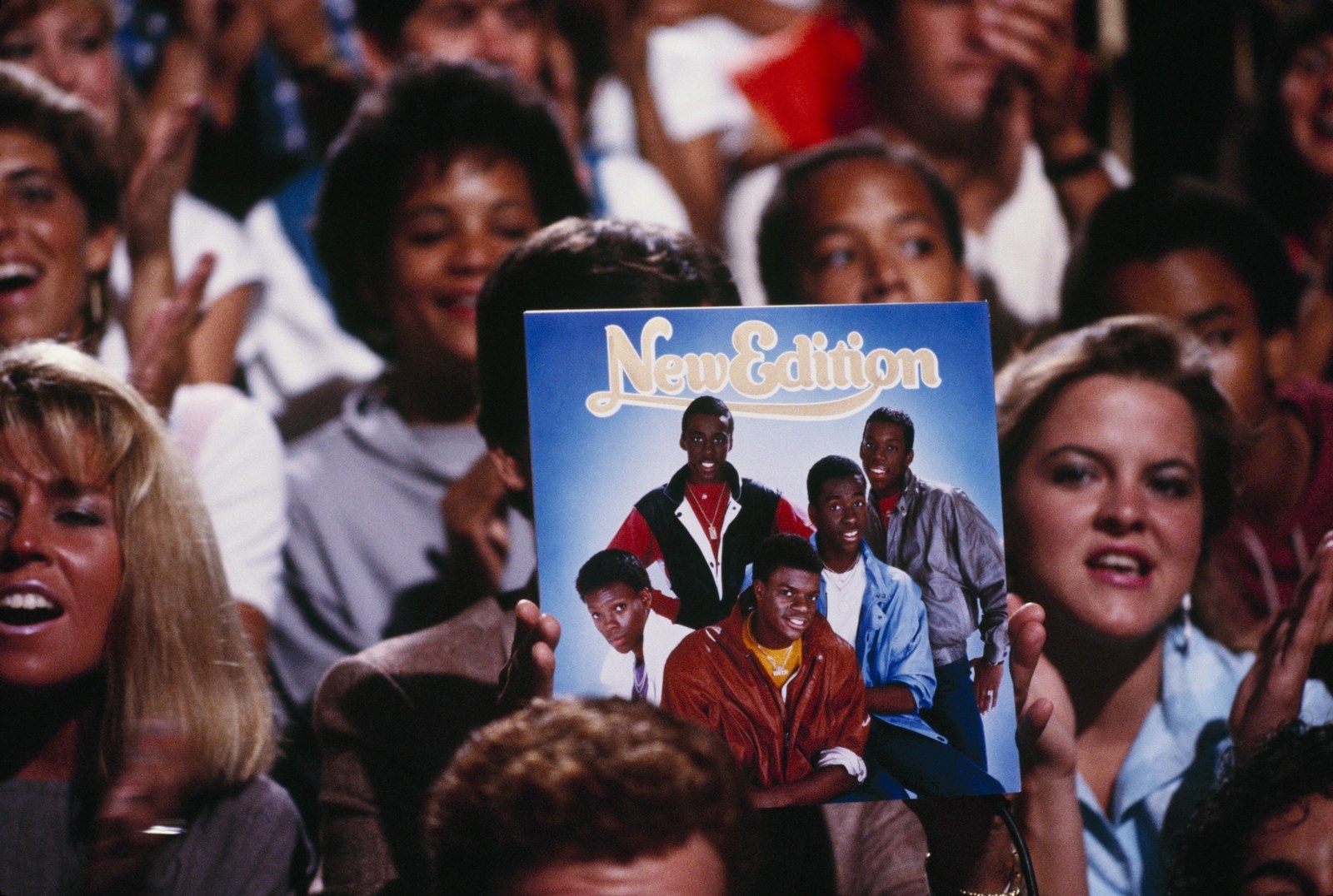

The most popular modern-day boy bands have been overwhelmingly white, but the prototypes that bore them, Menudo and New Edition, weren’t. Besides launching the musical careers of Ricky Martin and Bobby Brown, respectively, both groups were the rage in their own cultural communities. Menudomania — which naturally drew comparisons to Beatlemania — was an international phenomenon, taking “hold of Hispanic hearts” (according to a 1983 New York Times headline) across the globe and selling out four consecutive shows in Madison Square Garden. Another 1983 article recounted the pushing, fainting, and shrieking of their fans, which sounded like “metal scraping on metal.” When the group toured in San Salvador, the country ceased their civil war specifically for a two-hour concert (“MENUDO STOPS THE WAR” ran headlines).

Meanwhile, New Edition, founded in 1978 (a year after Menudo released their first album), built the modern boy-band format we’re most familiar with. The iconic R&B group, formed by five black kids from the Orchard Park Projects of Roxbury (the “heart of Black culture in Boston”), burst onto the scene with bouncy, bubblegum pop and evolved into a smoother, more mature sound buoyed by new jack swing. Though their name implied they were the “New Edition” of the Jackson 5, they never earned the same success with white audiences as the Motown family act. While Jackson 5 shows were mostly populated by young, black girls, breathless with desire — a 1970 Jackson 5 tour review recounts the calculated perfection of 10-year-old Michael’s crotch thrusts, to which “girls dissolved in blissful screams” — their white fans helped them cross over and rise up the pop charts. New Edition might have thrived on R&B charts, but the pop world was less friendly.

Like New Edition, Menudo met with challenges when trying to appeal to a wider American audience. Merv Griffin joked at one member’s expense over the language barrier between them. And in a 1998 issue of Vibe, former member Ray Reyes described how Johnny Carson treated them on The Tonight Show: “He started making jokes at our expense, dissing our language and our culture, talking in nonsense words.” A man beloved for his congeniality, Carson’s behavior was perplexing. Reyes suggested that Carson “didn’t know what to make of all the screaming we were getting from the audience.” One of the country’s most famous men was mocking something he didn’t understand or perhaps even felt threatened by: a dancing group of preteen and teen Boricuas.

It speaks to what seems like a greater and genuine insecurity: nonwhite men taking white men’s jobs away, even when the job is to simply be an object of attention (and therefore desire). Still, male fragility aside, Menudo and New Edition also had difficulty tapping into the white female audience to the same overwhelming degree as they achieved within their own race.

At the time (and maybe somewhat still), it was taboo for white girls to desire black or brown boys. And then there’s what these boys were incorrectly seen to represent: “In the context of the US, obviously there’s a long history in which to be a black man or a Latino man is to always already automatically be threatening,” said NPR journalist Jason King in a segment about the history of boy bands.

When New Edition parted ways with Maurice Starr, who helped helm their first album, Starr’s vindication would inadvertently set the (skin) tone of boy bands for the next two decades. “I said, 'Let me show them how smart I am,” Starr told Rolling Stone in 1989. “I'm coming back with a white teen group.'” That group was New Kids on the Block and, thanks to their massive merchandising campaign, they eventually topped Forbes’ list of richest entertainers for 1990 and 1991, beating high rollers like Oprah Winfrey and Michael Jackson. Girls bought NKOTB pillowcases so they could sleep with them, as well as NKOTB underwear; their obsessed fans wanted to be as intimate as possible with the group, even if they’d never meet.

Members of New Edition were incredulous watching the success of the NKOTB: “$800 million in T-shirts and stuff, man,” recalled Michael Bivins. “Damn, doll babies, and underwears, and blankets, and shit. Like, damn, man. Why we don’t got none of that?” It’s important to not overstress boy-band marketing at the cost of what they mean to fans, but in the case of NKOTB, they may owe their existence to it; Starr says he got the idea for NKOTB once he “noticed that the merchandise for New Edition wasn’t really selling to white kids, but it was selling to black [kids].” In a later interview, Starr reiterated, “I think if New Edition was white, they would have been just as big if not bigger than New Kids on the Block.”

Before long, the late and predacious Lou Pearlman sought to put together a group rocking a “New Kids on the Block look with a Boyz II Men sound,” and the Backstreet Boys answered the call. At the time, Boyz II Men were winning Grammys and breaking Billboard chart records left and right; Pearlman, seeing dollar signs, wanted that (i.e., undeniable singing talent) but whiter. Though the Backstreet Boys aren’t all white — AJ McLean and Howie Dorough are of Latin American descent — and they often paid tribute to black vocal groups they admired (such as Shai, Jodeci, and Boyz II Men), their complexions didn’t hurt in appealing to a wider teen audience.

The Backstreet Boys (whom PrettyMuch cites as an inspiration) achieved overwhelming success — selling over 130 million albums worldwide — which allowed other groups to tailgate their momentum. Some spawned from TV shows (O-Town), some came from across the pond (Westlife, 5ive) or up north (SoulDecision, the Moffatts), and its biggest rivals, the record-setting NSYNC, were from the same studio. They were all cute, all talented, all fun. And they were all primarily white. So when One Direction burst onto the scene well after this golden era of boy bands, they not only proved the timelessness of boy bands but also unknowingly tested the waters for their evolution.

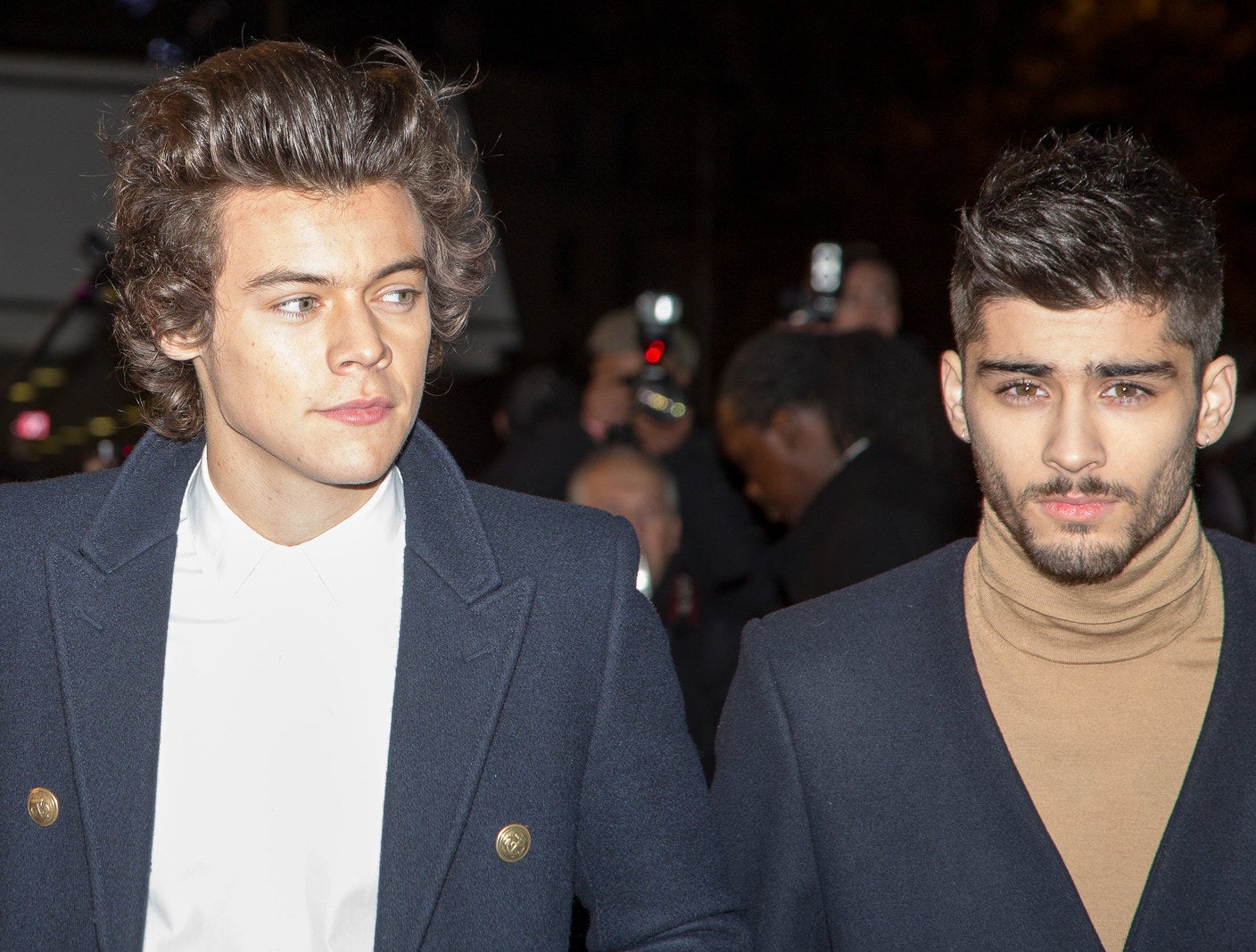

One Direction brought boy-bandom back into the UK and US mainstream in 2011, singing about being overwhelmed by hair flips, loving imperfections, as well as less chaste fare (“If you don’t wanna take it slow / And you just wanna take me home / Baby say yeah”) masked by handclaps and na-na-nas. But it was the devolution of the British Irish group that actually might’ve signaled the next step of their genre’s evolution. When Zayn Malik, who’s British Pakistani and One Direction’s only member of color, quit the band, fans went into hysterics, some requesting compassionate leave from work.

Zayn fared exceptionally well as a solo artist despite his shyness and anxiety: His 2016 debut album Mind of Mine and lead single “Pillowtalk” both landed at No.1 on the US and UK charts. Outside of music, he graced the covers of Fader and Vogue, collaborated on a fashion line with Donatella Versace, authored a New York Times best-seller, signed on to cocreate a TV show, and has a love life that continues to make headlines. His popularity remains steady (and relative to his former bandmates, only arguably surpassed by Harry Styles), hinting at how the face of boy bands could — and should — finally be different.

Brockhampton namecheck both Zayn and Harry as icons (and the former as a makeout partner) in certain songs, while calling themselves the “Southside One Direction.” They seem to love boy bands genuinely, but see the potential for them to be more. “The American idea of a boy band is, like, five straight, conventionally attractive white dudes. I come from a South Asian background, and I’m not supposed to be doing any of this,” said Romil Hemnani, the group’s DJ and producer, in an interview with the Guardian. “I’m supposed to be a doctor, or work at [a] 7-Eleven, or be an engineer. So, even the boy band thing, doing something out of the norm for my culture is big to me.”

A mix of young men who are black, brown, and white with varying looks and identities, the group — whose first major-label album comes out in June — seems unprecedented in mainstream music. But they’re determined to be seen as part of the boy-band lineage. In a tweet from August 2017, Kevin Abstract (née Ian Simpson), Brockhampton’s intrepid founding member who’s openly gay, put it plainly: “just cause we’re not white and some of us rap and like dick and dye our hair and make good music doesn’t mean we’re not a boyband.” The label can stay — it’s just the formula that needs updating.

Boy bands’ songs are changing too. The romantic ones are still there, but the mild negging (“Does the man even know you’re alive?”) has thankfully faded. While the group hasn’t released a full-length album yet, PrettyMuch’s material fits today’s social climate as well. In “Teacher,” the group sings about willingly having girls take the reins in a relationship. The single “10,000 Hours” nods indirectly to Malcolm Gladwell as they invest the time needed to make a relationship work. And “Would You Mind” has the boys wanting to pull their girl closer on the dance floor, but knowing they need consent first. (They also score points for offering a lift to said girl’s friends.)

Brockhampton’s lyrics push the envelope further. The band has songs about love and other sweet things, but also racism, anti-gay sentiment, mental health, and rape culture. It sounds stark for a boy band to address those topics — a bursting of a bubble — but considering the group’s growing fanbase, it clearly resonates with teens. In the documentary series, Kevin describes the audience and the reception: “It’s like 13–19-year-old girls and kids of color. Some of them are queer kids, some of them are just, like, angsty kids who hate their school and shit. And they’re just young and having fun.”

One thing that’s apparent once you spend time with PrettyMuch or watch Brockhampton content is their own joy and camaraderie. They’re also having fun. Boy bands of the past have used the theme of brotherhood as a selling point, something to charm fans, but in a way that looks and sounds increasingly artificial in retrospect. If the goal used to be giving young girls what they wanted, today it feels like boy bands are serving their fans and themselves at the same time. (That said, the allegations against Brockhampton’s Ameer are a reminder that every boy band is still, inevitably, made up of individual boys — and not every member’s actions in real life will always align with the ethos or image their group collectively projects.)

By embracing the boy-band label, these groups are inherently affirming the people who love them: girls and queer teens. They aren’t ashamed of their fanbase and don’t obsess over whether or not they’re taken seriously as “artists.” And as self-described fans of previous boy bands and other male music groups, they seem to recognize the power of fandom and what it can inspire. It’s this respect and understanding of the power of boy bands and their fans that might mean more than their music or lyrics ever could.

Ultimately, the new wave of boy bands feels fresh because of the way they seem to be taking ownership over their narrative, instead of having it dictated to them. “I'd rather tell somebody that I'm in a boy band and prove to them that we're dope, versus telling them I'm in a boy group and try to hide the weird stigma,” says Edwin. “It's like no, we're just making music the way we know.”

When I ask PrettyMuch why they so readily call themselves a boy band, a few of the boys respond in unison. They offer the same answer that Brockhampton’s Matt Champion once gave nonchalantly to the same question: “It’s just what we are.” ●

UPDATE

As of May 27, following allegations of his abusive behavior toward women, Ameer Vann is no longer a member of Brockhampton.