A Partial History of Headphones

Modern headphones have their origin in opera houses, military bases and a kitchen table in Utah

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/83/86/83863bc6-4760-41a6-9c6c-2e90d3648852/koss-sp3.jpg)

It’s nearly impossible to walk around a city or college campus or shopping mall, or really anywhere these days, without seeing at least a few dozen people wearing little earbuds stuffed into their ears, or even huge headphones that look like something a 747 pilot might wear. The ubiquity of modern headphones could perhaps be attributed to the Sony Walkman, which debuted in 1979 and almost immediately became a pop culture icon. As the first affordable, portable music player, the Walkman became such an prominent characteristic of the young urban professional that it was even featured on the cover of The Yuppie Handbook. But of course, the history of headphones dates back further than the 1980s. Like many commercial electronics, modern headphones (and stereo sound) originated, in part, in the military. However, there’s not a singular figure or company who “invented” the headphones, but a few key players who brought them from military bases and switchboards into the home and out to the street.

In the 1890s, a British company called Electrophone created a system allowing their customers to connect into live feeds of performances at theaters and opera houses across London. Subscribers to the service could listen to the performance through a pair of massive earphones that connected below the chin, held by a long rod . The form and craftsmanship of these early headphones make them a sort of remote, audio equivalent of opera glasses. It was revolutionary, and even offered a sort of primitive stereo sound. However, the earliest headphones had nothing to do with music, but were used for radio communication and telephone operators in the late 19th century.

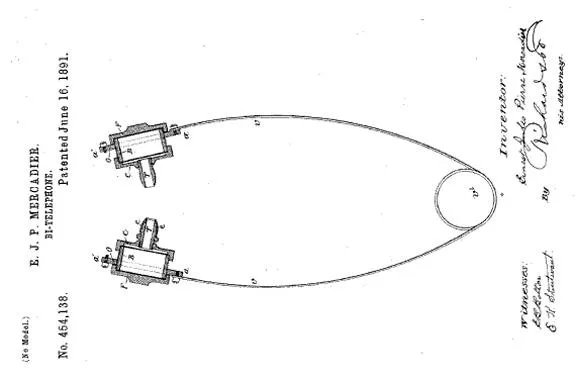

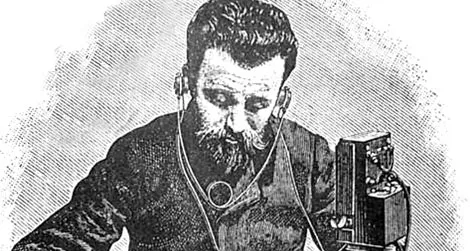

Before the Electrophone, French engineer Ernest Mercadier patented a set of in-ear headphones in 1891, as engineer Mark Schubin noted in an excellent article on the history of headphones. Mercadier was awarded U.S. Patent No. 454,138 for “improvements in telephone-receivers…which shall be light enough to be carried while in use on the head of the operator.” After extensive testing and optimization of telephone receivers, Mercadier was able to produce miniature receivers that weighed less than 1 3/4 ounces and were “adapted for insertion into the ear.” His design is an incredible feat of miniaturization and is remarkably similar to contemporary earbud headphones, down to the use of a rubber cover “to lessen the friction against the orifice of the ear… effectually close the ear to external sounds.”

Do telephone headsets go back further than Mercadier’s 1891 patent? Sort of, but they’re almost unrecognizable shoulder harness-like objects that barely meet the definition by today’s standard. So let’s flash forward to the birth of the modern headphones.

In the years leading up to WWI, it wasn’t uncommon for the Navy to receive letters from small businesses and inventors offering up their unique products and skills. In 1910, a particularly memorable letter written in purple ink on blue and pink paper came from Utah native Nathaniel Baldwin, whose missive arrived with a pair of prototype telephone headsets offered for military testing. While the request wasn’t immediately taken seriously, the headphones were eventually tested and found to be a drastic improvement over the model then being used by Naval radio operators. More telephones were requested for testing and Baldwin obliged at his own expense.

The Navy offered Baldwin some suggestions for a a few tweaks, which he promptly incorporated into a new design that, while still clunky, was comfortable enough for everyday use. The Navy placed an order for Baldwin’s headphones, only to learn that Baldwin was building them in his kitchen and could only produce 10 at a time. But because they were better than anything else that had been tested, the Navy accepted Baldwin’s limited production capabilities. After producing a few dozen headphones, the head harness was further improved as its design was reduced to only two leather-covered, adjustable wire rods attached at each end to a receiver that supposedly contained a mile of copper wire. The new headset proved to be an immediate success and the Navy advised Baldwin to patent this new model of headphone. Baldwin, however, refused on the grounds that it was a trivial innovation. In order to increase production, the Navy wanted to move Baldwin out of his Utah kitchen and into much larger East Coast facility. But Nathaniel Baldwin was a polygamist and couldn’t leave Utah. Another manufacturer, the Wireless Specialty Apparatus Co., got wind of the situation and worked with the inventor to build a factory in Utah and manufacture the headphones. The agreement with Wireless Specialty came with one enormous caveat: the company could never raise the price of headsets sold to the U.S. Navy.

The next big innovation in headphone design came after the second World War, with the onset of stereophonics and the popular commercialization of the technology. Record label EMI pioneered stereo recordings in 1957 and the first commercial stereo headphones were created a year later by musician and entrepreneur John Koss, founder of the Koss Corporation. Koss heard about a “binaural audio tape” from a friend and was thrilled to hear how it sounded through a pair of military grade headphones. Determined to bring this sound to the public, Koss developed an entire “private listening system,” the Koss Model 390 phonograph, for enjoying music that included a phonograph, speaker and headphone jacks all in one small package. The only problem was that there were no commercially available headphones that were compatible with his new phonograph. They were all made for communication or warplanes. Koss talked with an audio engineer about this and they quickly rigged up a pair of makeshift prototype headphones. “It was a great sound,” Koss remembers. The design was refined built from two vacuum-formed brown plastic cups containing three-inch speakers protected by a perforated, light plastic cover and foam ear pads. These were connected by a bent metal rod and the Koss SP-3 headphones were born. “Now the whole thing was there,” remembers Koss. Music lovers embraced the stereophonic headphones due to their enhanced sound quality, which was made possible by the use of different signals in each ear that could closely approximate the sounds of a concert hall. The design was well received when it debuted at a hi-fi trade show in Milwaukee in 1958 and was almost immediately copied by other manufacturers, standardizing the design of headphones around the world for years to come.

An interesting footnote to this story is the suggestion from media theorist Friedrich Kittler that, while Koss may have created the first truly stereo headphones, the first people to actually experience stereophonic sound through headphones were the members of the German Luftwaffe during World War II.

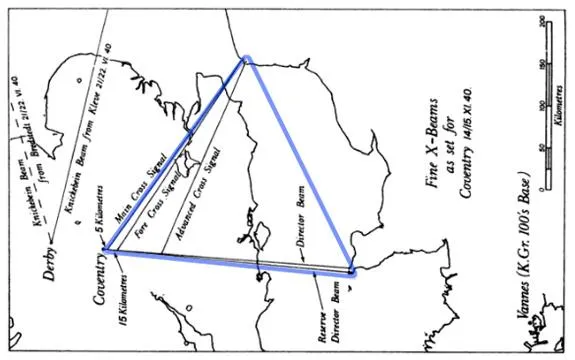

In his book Gramophone, Film, Typewriter, Kittler describes the innovative radar system used by the German Airforce during World War II, which allowed headphone-wearing pilots to reach the destinations and bombers to accurately drop payload without visually seeing their targets:

“Radio beams emitted from the coast facing Britain…formed the sides of an ethereal trailing the apex of which was located precisely above the targeted city. The right transmitter beamed a continuous series of Morse dashes into the pilot’s right headphone, while the left transmitter beamed an equally continuous seres of Morse dots–always exactly in between the dashes–into the left headphone. As a result, any deviation from the assigned course results in the most beautiful ping-pong stereophony.”

When the pilots reached their target, the two radio signals merged into one continuous note. As Kittler writers, “Historically, had become the first consumer of a headphone stereophony that today controls us all.”

The above mentioned designs are only a few of the more prominent developments in the history of personal audio. It’s likely that there are even earlier inventions and it’s certain that there are many, many other individuals who should be thanked for their contributions to the development of the modern headphones that let us shut out the roar of plane engines with music, listen to play-by-play analysis while watching a baseball game in person, and strut down the street to our own personal soundtracks.

Sources:

Captain Linwood S. Howeth, USN, “The Early Radio Industry and the United States Navy,” History of Communications-Electronics in the United States Navy (1963): 133-152; Peter John Povey and Reg A. J. Earl, Vintage Telephones of the World (London: Peter Peregrinus Ltd., 1988); Friedrich Kittler, Gramophone, Film, Typewriter, trans. by Geoffrey Winthop-Young and Michael Wutz (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1999); Virginia Hefferman, “Against Headphones,” The New York Times (January 7, 2011); Mark Schubin “Headphones, History, & Hysteria” (2011), http://www.schubincafe.com/2011/02/11/headphones-history-hysteria/; “Koss History,” http://www.koss.com/en/about/history; Google patents

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)