Not so long ago, I was waiting for my order in a Chinese takeaway when I Believe I Can Fly by R Kelly came on the radio. No one paid a blind bit of notice. The DJ didn’t make any comment about Kelly. It was just another song, another five minutes to fill up the airwaves.

Would that happen now? Finally, after years of the stench of sexual misconduct following him around like a swarm of gnats, Kelly may have reached his tipping point. It is true he has never been convicted of anything, but he has settled out of court with women who have accused him of sexual offences, and almost no one, at this point, has come forward to defend him. That is thanks in huge part to the reporting of the Chicago journalist Jim De Rogatis, who has spoken to and – crucially – listened to so many of the women who wanted to talk about what Kelly did to them.

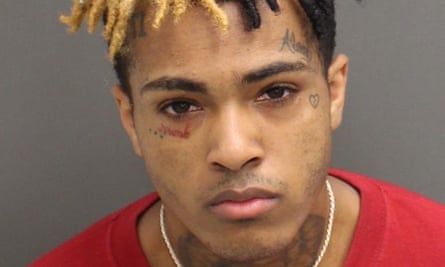

Yet despite the years of stories about Kelly, until last week the music industry had never taken action against him. Then, last Friday, Spotify announced that under the terms of its new policy on “hate content and hateful conduct” it would be removing Kelly’s music from its own playlists, alongside that of XXXTentacion, who is charged in Florida with aggravated battery of a pregnant woman and witness tampering. You can still find Kelly without much trouble – he still has his own artist page – but Spotify will no longer promote him. Rival streaming services Apple Music and Pandora followed Spotify in removing Kelly from promoted content.

“When we look at promotion, we look at issues around hateful conduct, where you have an artist or another creator who has done something off-platform that is so particularly out of line with our values, egregious, in a way that it becomes something that we don’t want to associate ourselves with,” Jonathan Prince, Spotify’s head of content and marketplace policy, said when the decision was made. (When I contacted Spotify to ask about the implementation of the new policy in future, I was told it had no further comment to make.)

Spotify’s decision followed the #MuteRKelly campaign, which has been calling for anyone profiting from his work – including ticket agencies, streaming platforms and his label, RCA – to sever ties with him. Women of Color of Time’s Up supported the cause (“We demand appropriate investigations and inquiries into the allegations of R Kelly’s abuse made by women of color and their families for over two decades now,” it said in a statement), as did celebrities including John Legend and Kerry Washington.

While you will struggle to find anyone – bar Kelly and XXXTentacion – who thinks Spotify has committed a grave injustice, it’s worth remembering that this is not a decision based on morality alone. As the philosopher Julian Baggini notes: “What’s kind of lamentable about things like this is that when companies like Spotify do make these choices, they’re driven not by consistent moral principle but by the need to react to the latest public outrage. Using ethical criteria [to make business decisions] is reasonable, but in practice this isn’t about ethics. Public outrage is very rarely accurately linked to moral seriousness.”

The same fear of public outrage drove the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences to expel Roman Polanski and Bill Cosby earlier this month. But while the decision concerning Cosby made sense, the one about Polanski was odder. Cosby was only recently convicted of sexual assault; Polanski pleaded guilty to unlawful sexual intercourse with a minor in 1978, fleeing the US when he believed the terms of his plea bargain were going to be ignored by the judge. His offence has not altered in seriousness since then, yet the Academy admired Polanski enough to award him the 2002 best director Oscar for The Pianist. Only now, with #MeToo in full swing, is he considered persona non grata, and despite scores of allegations against myriad Hollywood stars, directors and executives, only Cosby, Polanski and Harvey Weinstein have been expelled for sexual misconduct (the only other person expelled from the Academy was actor Carmine Caridi, after he was found to have shared a copyrighted DVD of a film with someone who uploaded it to the internet).

The apparent randomness of the Academy’s behaviour does not necessarily mean its actions are inadequate, though. Think of it as pour encourager les autres. As Baggini points out: “A large part of moral sanction is about modifying behaviour in the future. People are always products of their time, but you condemn things and take action with the purpose of affecting the future.”

One of the problems with policing morality – especially for Spotify, and for YouTube as it tries to clamp down on hate speech and fake news – is the scope of what is required if they are to be consistent. Which is why action seems to happen only when mass sentiment demands it. Earlier this year, after the Marjory Stoneman Douglas high school massacre, YouTube cracked down on the “alt-right” site InfoWars, which had been publishing videos suggesting survivors were “crisis actors” with a political agenda. Yet countless other conspiracist and fake news videos went untouched – including, as Wired noted, InfoWars videos claiming the Sandy Hook school massacre had been a hoax. For all YouTube’s boasts about increasing its number of moderators to 10,000, about how it assiduously removed 8.3m videos in the past three months of 2017 – 76% of them unviewed – the fact is that, as Wired observed: “The pattern of waiting until something is brought to YouTube’s attention to do anything meaningful will likely continue.” (YouTube did not respond to a request for comment.)

Volume is as much of an issue for music sites. XXXTentacion responded to Spotify’s action with a long list of other artists accused of assorted offences, including David Bowie, Miles Davis and James Brown, asking if Spotify would be removing them from its playlists. Kelly’s management issued a similar statement, asking if Spotify would continue promoting “numerous other artists who are convicted felons, others who have been arrested on charges of domestic violence and artists who sing lyrics that are violent and anti-women in nature”.

In fact, Spotify’s policy is far from ad hoc. It was drawn up in conjunction with a variety of US pressure groups, including the Southern Poverty Law Center, the Anti-Defamation League, Color of Change, Showing Up for Racial Justice, the LGBTQ group GLAAD, Muslim Advocates and the International Network Against Cyber Hate. The policy itself asserts the various transgressions that could see an artist removed from playlists (though not from the platform, on which Gary Glitter and Lostprophets remain, though without dedicated artist pages; the black metal artist Burzum, a convicted murderer, has his own artist page), but then reminds the reader: “It is impossible for us to manually review all of the content on Spotify,” and asks for users’ help in alerting it to offenders. In other words: the policy might not be ad hoc, but its implementation will be.

But behind all this is one other question: why doesn’t RCA drop him, as #MuteRKelly has suggested? The answer is simple, says Chris Brown, a solicitor at the specialist music business law firm Sheridans: there’s a contract. “I’ve not seen many moral turpitude clauses in record deals that include the idea of bringing the label into disrepute. And if labels don’t have that right in there they may leave themselves open to a claim from artists for potentially being in breach of the agreement.”

What about the possibility that Kelly is unable to fulfil his contractual duties? If he can’t get promoted on Spotify, might that not mean he is unable to perform his job as specified? “There’s a chance there would be a publicity clause whereby the artist is obliged to use his best endeavours to promote a record, which would involve doing TV and radio interviews, and if no one wanted to interview them, they might be in breach,” Brown says. “But it would depend on the wording of the clause, and it would be difficult to run.”

Brown does expect artists’ contracts with labels to change in the wake of Time’s Up. “I think it’s entirely likely that behaviour clauses will happen. I’ve had experience of labels being nervous of artists who behave outrageously and how that will reflect on the label. That’s only going to be amplified, given the change in attitudes.”

But without immediate outrage about specific incidents, it’s hard to imagine any great appetite to go purging the past. That’s not because no one takes seriously the offences that assorted artists are accused of, but more because of our own complicated relationship with art. The feminist writer Sarah Ditum notes her love of plenty of artists whose behaviour to women would be considered appalling, but observes that she can’t bring herself to write off Ike Turner’s Rocket 88, despite his violence towards Tina. “My dad’s a massive collector of blues and soul and early rock’n’roll. That’s hugely important to me, because it was my first entry into the world of music, and because of what it says about my relationship with my dad. I feel a reflexive kick against the part of me that would purge it all.” As someone who writes primarily about music, I’ve turned down the chance to interview artists whose behaviour I have found distasteful, but I’ve also interviewed Led Zeppelin’s Jimmy Page – whose girlfriend in the 1970s was the underage Lori Mattox – more than any other musician, because I love Led Zeppelin too much to cut them loose.

Even as a feminist, Ditum feels that in the case of R Kelly, Spotify has gone far enough – not promoted, but not expunged. “I think it’s weird when institutions make decisions for us about what we can hear or see. When everything was physical, even if a label or a publisher took something out of print, there were still copies in circulation. But if things are taken out of circulation online, they stop existing, and that takes away the possibility of us making our own decisions.”

For now, Spotify says it will make decisions about what music it promotes on a case-by-case basis. Which means, in practice, that the historic perpetrators of violence and abuse will probably remain untouched. Instead, wait for the next star to be called out in public, for the backlash to begin, and then for many in the music industry who have known the stories for years to jump into action. Same as it ever was.