One of the first things I thought about when I heard that Glenn Branca had died from throat cancer at the age of 69 earlier this week, is the sound that the electric guitar makes when feeding back uncontrollably — and about what the person cradling that screaming guitar may be liable to do next.

Many people, when confronted with the metallic squall of an electrical signal making its boisterous return back from the point of amplification, try to extinguish it. Back when America was supposedly great, this desire to reestablish a quieter, more organized sound space was commonly regarded as “normal.” But much of the last five decades in music — popular, definitely; art, more than most high-brow institutions admit — has been determined by subverting technology. And one of the remaining, defining soundtracks of the so-called American century is the incomplete survey of such unholy dins made by the products of once-legendary manufacturers such as Fender and Marshall squaring off in deafening, high-pitched battles.

Which is why the image that cracked open my head was not that of a hand reaching for a volume control, but of numerous bodies rushing toward the amp to further instigate the cacophony — or maybe to control it, not for the purpose of suppression, but of deliverance. The identity of the perpetrators changing continuously — the noise setting them all free.

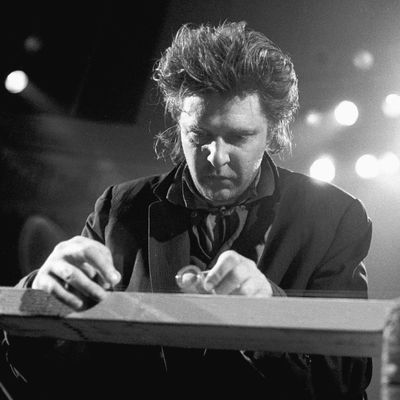

It is my understanding that Glenn Branca — one of the handsomely scruffy members of New York’s legendary art downtown of the 1970s and ’80s, child of two musical liberation theologies (John Cage minimalism and CBGB’s punk rock), who wrote his name in the canon by composing symphonies which featured anywhere from a “few” to a “shitload” of amplified six-string instruments — recoiled at the idea of being known as the “guitar guy.” He had a point.

Instead, Branca was an ideas guy with a sense of charismatic, puritanical independence formed not only by the fires of the creative revolts he immersed himself in, but by the social and economic constraints that guided the increasingly colossal act of his creation. The dramatic scale of the work kept building, and his stature as chain-smoking champion sage of the city’s experimental music codified into an essential New York story, but Branca’s anti-Establishment streak never allowed him to climax uptown.

Though guitars feature prominently in every single one of his works — from the fuel-injected Ramones-like romp of the short-lived rock group, Theoretical Girls, to the 16th and last (?) symphony he premiered during his lifetime (subtitled, “Orgasm”) — they were merely conduits, not meant to be played either unaccompanied or with virtuosity. As with many works of 20th-century art that embraced the reductive notion that less could be much much more — even when “less” meant a hundred guitars — Branca’s blowouts contained the appearance of ragged democracy, a sense of collectivism, advocating a lack of technique that seemed to evolve into a kind of technique itself.

When experienced live, his long pieces especially became a kind of fever dream come to life, in which the right progression, if executed with enough force and volume, by enough people, could indeed work to lift you out of the bodily confines and set you free. “You start hearing choirs singing,” Branca told Robert Barry at The Quietus a few years ago, “and that’s kind of what I’m after.” Of course that sort of spiritual definition is too limiting; and so, somewhat wisely, he added, “Actually, depending on where you put your attention … everybody in the audience is really hearing something very different.”

The expression of that sort of freedom is a powerful narcotic. Even if you are not an immigrant kid whose formative art years were overseen by a materfamilias rooted in the musicological and literary wings of a totalitarian state with a cultural legacy that pitted proletarian social realism against the classical romanticism of the overeducated. Both equally hopeless; I was/am.

The America I found myself slouching towards in 1976 contained the promise of another way forward — as well as a set of myths I’ve been struggling to unspool ever since. At the time, it didn’t matter that I had no idea I was landing in a New York seized by revolution; my attention to possibility was already becoming radicalized from seeing the size of a Cadillac and of the World Trade Center, from watching Julius Erving fly through the air, from tasting a kiwi fruit, and from hearing Saturday Night Fever and Chuck Berry pump out of the radio. All real-life monuments to the imagination.

Of the senses, it was sound that best helped map this imagined future, providing kinship in navigating the journey that began at “freedom from” and headed towards “freedom to.” After an ensuing decade-plus of crisscrossing daydream nations and traversing diamond seas — because, of course, I only learned about Glenn’s work from interviews with Sonic Youth members who’d met in his Ensemble in the early ’80s (Neutral, Branca’s label, also put out their first records, as well as the first Swans album) — arriving at one of his performances (sometime around ’95 or ’96, at the Kitchen) seemed like the most obvious thing in the world. Which now, considering all the circumstantial pomp, amplified drang and living mass that goes into bringing one together, seems a little odd. I plugged right in. Its largesse and scope returned me right back to the 7-year-old who’d just seen his first skyscrapers — the very towers Branca would bring a hundred guitars to for a performance in the summer of 2001, before planes knocked them down.

Aging has required extricating the liberties I’d once attributed to America in Branca’s work from it. Without a doubt, they’re still in the DNA of all his pieces, but the luster’s worn off America’s contribution; the purpose and the process of her dreams are more shadowy. Certainly America doesn’t imagine as big as she used to. In fact, the whole notion of grand thinking has changed as well — should we even bother, with the planet dying and all? So have the tools with which to try to make them come true.

Branca seems to have intuited this. In 2016, before a Red Bull Music Academy gig that staged three of his symphonies, he gave a somewhat grumpy interview, declaring that, “the Grand Epic is over.” At first, he seemed only to be burying New York’s cultural heyday, but he soon widened the casket — “there will never be another John Coltrane. There will never be another Allen Ginsberg” — even getting in a dig about the “people [who] just want to go to discos.” The quote had a “lion in winter” quality to it, yet the funeral he was describing was of the cult of the “great man,” not of a culture-at-large, a culture he helped create and whose progress he continues to inspire. It may never have been as democratic as advertised, but the power and range of its feedback has only grown.