In April of 2013, I called my friend Caroline Shaw with some wonderful news: She had just received the Pulitzer Prize for music. (Caroline wrote her piece, Partita for 8 Voices, for Roomful of Teeth, the vocal ensemble I help organize.) We laughed hysterically. How could Caroline, virtually unknown as a composer, have won? “They must not have had any choice!” I remember saying. Her piece was so good that when she had shown me the final version a few months prior, I had offered to submit it to the Pulitzer committee myself, just for fun. I never did. Much to my delight, however, Caroline had gone and done it herself. The committee saw the light. In that private moment before Caroline’s phone blew up (and it hasn’t stopped—she has since collaborated with everyone from Renée Fleming to Kanye West), we marveled at the circumstances. Somehow, we concluded, the process had worked.

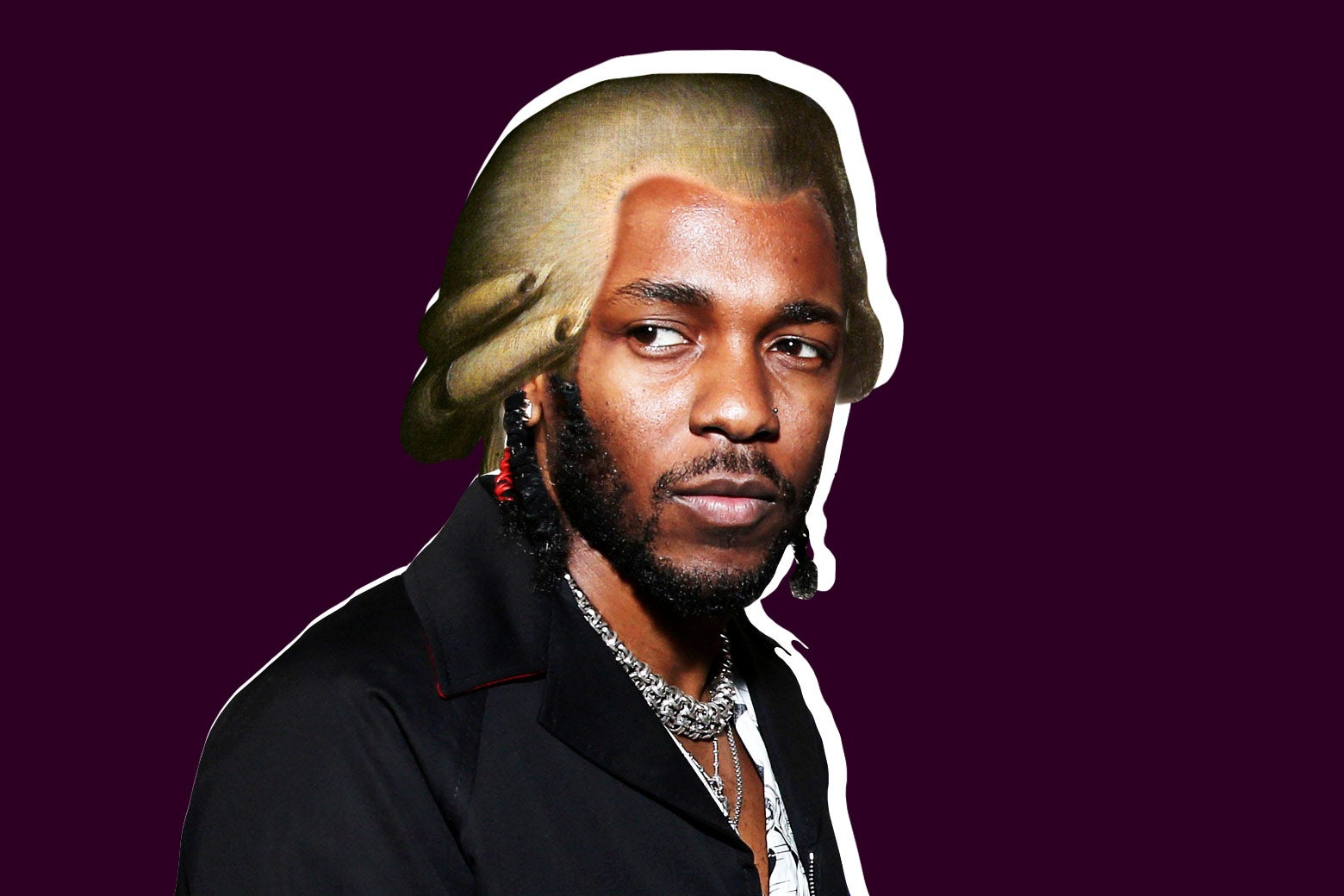

Many classical fans and musicians celebrated. The committee had lowered the barriers keeping everyone other than well-established academics and the occasional jazz musician out and had invited someone else in, because, simply, she had written the best piece in the applicant pool. (It has since become one of modern music’s most beloved classics, often topping lists of the best modern classical pieces of the 21st century.) There were some sour grapes too, but the acrimony pales in comparison to what we’ve seen this week after Kendrick Lamar’s Damn earned this year’s coveted prize, the first hip-hop album to so do. Yes, many, including the finalists who lost to Lamar, are cheering the award, hailing it as the tumbling down of another oppressive wall of musical segregation. But others are decrying it as the end of classical music—and, sure, civilization—as we know it.

I must confess I’d only listened to Lamar’s music casually until this week. But the Pulitzer changed that, which is precisely the point. It is not just that the jury declared Lamar’s music worthy of its prestige, though that certainly is momentous, but also that they would like me, and other classical musicians and devotees, to do what we so often demand of others: to broaden the scope of our listening, to recognize musical genius outside of our usual purview and comfort zone.

Why, I must now ask, did I not fully appreciate Lamar’s tight control of Sprechstimme, the stodgiest academic description one can imagine for his vocal style: spoken, yet almost sung, not dissimilar to efforts by composers from Leoš Janáček, to Arnold Schoenberg, to Luciano Berio, but also Eazy-E, Tupac Shakur, and Eminem? Why did I not enjoy his vocal lines as scrupulously controlled “cells” of repeating pitches, slowly evolving in much the same way as the best works by Steve Reich and Philip Glass? Why did I not notice cathartic metric modulations that would have made Elliott Carter, the father of this technique in classical music, swoon with jealousy? Why did I not notice that Lamar’s tightly controlled beats and instrumentals are not just platforms for his vocals but are, unto themselves, akin to expertly controlled musical plate tectonics, slowly but relentlessly shifting, creating subtle and yet epic movements—what we in the classical music world would hear as a sophisticated and successful form of post-minimalism?

The answer is that I had not heard Lamar’s album front to back, an exercise that permits such features to become superbly and supremely obvious. I had not approached his music with the focused attention that I bring to other music that I love, from Bach to Oscar Peterson. The difference is moving beyond simply hearing music and progressing toward the act of genuine, focused, active listening. Not hearing all of Damn in succession is no different than a casual listener trying to understand the full wonder of Handel’s Hallelujah chorus without having listened to the preceding two hours that lead up to that riveting moment. Yes, you can enjoy it out of context, but you simply cannot fathom its power and are thus deprived of its abiding emotional reverberations. Lamar’s Pulitzer implores serious and careful admirers of all music to contemplate hip-hop just as seriously as we engage with a baroque oratorio or a modern opera.

Many in the classical world are unmoved. Online, a debate flared up instantaneously, including some ugly takes. The usual “this isn’t serious music” cohort has predictably taken up shop in one corner. Historically, these types are usually soon forgotten, but they occasionally show up as the objects of ridicule in essays decades later when we are grappling with how it was that towering musical achievements were underappreciated in their own time. These are among the same people who are apt to bemoan the loss of prestige that will somehow befall the Pulitzer because the award has been bestowed upon someone who did not attend a music conservatory. (I assure you, next year’s winners won’t care.)

Among the stranger and related arguments against Lamar’s prize is that classical and jazz composers somehow need the Pulitzer Prize, because it remains one of the only universally understood accolades outside of fancy music circles. While a Pulitzer can enhance a career (or launch one, as it did for Caroline), I would argue that classical music—and to a lesser extent, jazz—needs to listen to Damn more than any one composer needs to have their career boosted by this year’s prize. A good Pulitzer causes me to expand my horizons, not confirm them. While it is fun when I personally know or have met the winner or some of the finalists, those years have not been ones in which my musical palette was particularly expanded by the award. Too many of my colleagues are wedded to the notion that prizes like the Pulitzer somehow validate the ascendancy of our particular kind of music over others—and that by proxy, that validation rubs off on them when someone they know, or even know of, wins the award. When the award strays from the predictable list of “major” composers, a scary message comes along with it: You don’t have your finger on the pulse of your own field. This too must be frightening. So many of my colleagues are scared to open their ears and their hearts to music that has not yet been deemed worthy of inclusion into our cherished concert halls or textbooks, especially when that music is not written down. To them, losing the Pulitzer—and not to just another composer but to another genre of music altogether—is an existential threat directed at classical music’s collective sense of superiority.

Those feelings might be right. But they are wrong to care. If other forms of music are pitted against ours, it is true that our music will not always win, even if we are the gatekeepers. (Each Pulitzer committee, including this year’s, is made up of jurists who are far more likely to know the music of Copland and Coltrane than Lamar.) But composers, if your music flows from within and manages to reach others, people will still commission music (and, yes, even pay to hear it) whether or not there are prizes associated with it. The privilege to make music for a living is one you will still have earned, and one that I am personally envious of—even though I love my day job. One of my composition teachers, Robert Suderburg, told my classmates and me that “Creating new music is the greatest gift we can ever give to people.” For classical composers, that is certainly true. But if we permit ourselves to draw on an ever-expanding palette of influences, those gifts will become even greater.