In 1997, Aerosmith released an ode to the female anatomy, simply titled Pink, in which Steven Tyler famously brayed about his tremendous love of a woman’s vagina. Every line began with the declaration “Piiiink…”, followed by a cheeseball rhyme scheme describing a variety of sexual situations. Subtle it was not.

Fortunately, more than two decades later, R&B-soul luminary Janelle Monáe has rescued us from a lifetime of negative Aerosmith-word associations by taking back the song title, teaming up with art-pop nymph Grimes and swapping out the I for a Y. In 2018, we get Pynk, a silky, joyful, funk-fused gem that, like the Aerosmith track, is about the vagina and also starts each line with the word “pink”. But where Tyler was blunt and blundering, Monáe is slick and sophisticated.

Like the alternative spelling of “womyn”, Pynk finds Monáe keen to explore a world free from male influence. In the song’s vibrant music video, the star, who has never officially defined her sexuality except to deem herself “sexually liberated”, dances in triangular, ruffled “pussy” pants, throws a ladies-only house party, shows off unshaven pubic hair and nuzzles actor Tessa Thompson. She praises the female form and the nirvana between her legs (“Pink like the paradise found”). Men don’t figure into the song’s equation, unless it’s to dismissively point out that they’ve “got blue”. Which is fine, because “we’ve got the pink”.

Critics have hailed the song as a must-hear girl power anthem, while the lesbian community has praised its accompanying video for beingdeeply erotic and artistically groundbreaking.

Celebrating female sexuality in pop music is nothing new, of course. But has it ever been this For Women’s Eyes Only?

Madonna set a new bar for mainstream erotic expression in the early 80s when she famously humped the 1986 VMA stage in white lace, singing about how she’d found a lover so good that it made her feel like – well, you remember. In the next decade, she morphed from a newly liberated “virgin” to a proud dominatrix, publicly experimenting with then-taboo subjects like sadomasochism and BDSM on her fifth studio album, Erotica, and her carnal-noir 1992 coffee-table book, Sex.

Later, in the pop music boom of the late 90s and early 00s, legions of stars and would-be stars followed in Madonna’s stead, though they arguably took the “sexy virgin” thing a lot more literally than their 80s idol. In 1999, a teenage Britney Spears popularized short schoolgirl skirts and pigtails with her debut video for … Baby One More Time and posed for the cover of Rolling Stone in skimpy PJs with a plush Teletubby in one hand and a phone receiver in the other.

On her third album, though, a now twentysomething Spears showed off her sexually empowered side, opting for breathy, moaning vocals on 2001 single I’m A Slave 4 U and open-mouth kissing Madonna herself in 2003 at the VMAs alongside another newly “dirrty” pop performer (and fellow Disney Mouseketeer) Christina Aguilera.

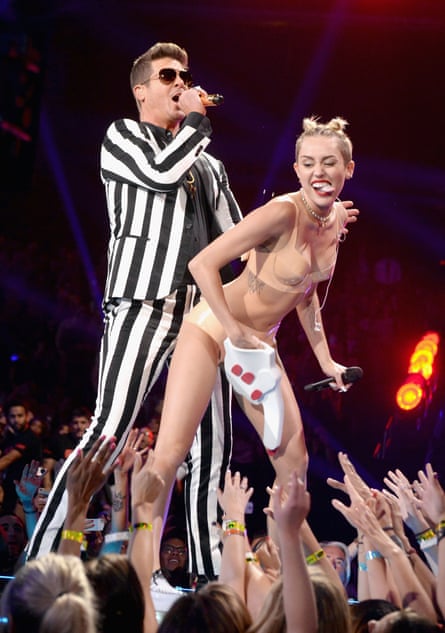

It’d be nice to think that the virgin-discovers-sex pop music narrative had worn itself out in recent years, but still, they persisted, with the once family-friendly Miley Cyrus bursting out of a child’s toy (a teddy bear) at the 2013 VMAs and rubbing up against Robin Thicke (among other things, like posing for alleged sexual predator Terry Richardson).

Or how about Selena Gomez, who, after years of Barney and Disney, declared herself a proudly sexual being in 2013 by donning a black lace corset and cooing that “when you’re ready, come and get it (na, na, na, na)”.

Frustratingly, as cliche as the story is, it’s clearly still a money-maker. And as much as you’d want to congratulate those singers on taking ownership of their sexuality, it’s hard to forget that their awakenings are conveniently designed for male enjoyment and objectification.

In other instances, pop singers eschewed the chaste image entirely, sometimes appearing to explore bisexuality and lesbianism, like Katy Perry, making her grand entrance in the late aughts by declaring that she kissed a girl, and she liked it. (Though, of course, she hopes her boyfriend don’t mind it.) Six years earlier, female Russian duo Tatu titillated audiences by touching tongues in soaked-through schoolgirl outfits in the video for their one-hit wonder All The Things She Said.

Though on the surface mainstream pop’s dalliance with bisexuality and lesbianism appears progressive, a second look reveals tracks like Perry’s and Tatu’s as shallow – like drunken college-age girls kissing on a dare from their boyfriends. Or like lesbian porn created by and for men, or even Blue Is The Warmest Color director Abdellatif Kechiche encouraging lengthy and later deemed unrealistic lesbian sex scenes that left the film’s stars feeling exploited.

Pynk, however, is totally unconcerned with male titillation and builds on the theme from Monáe’s earlier single, bisexual anthem Make Me Feel, which essentially declares its singer’s attraction to humans, not genders. Against crisp finger snaps and skittering synth, Monáe takes her appreciation of the female form a step further by pointing out the color of a woman’s anatomy, referencing the vulva, vagina, the brain, tongue and eyelids, and she recites the ways her color of choice symbolizes sexual passion and revelry (“I wanna fall through the stars / Getting lost in the dark is my favorite part”).

Think of the possibilities that Pynk provides: perhaps, thanks to Monáe, young women will have a more realistic portrait of what being queer means. On the other hand, maybe they’ll be more assertive in telling their partners what they like. Maybe they’ll feel more at ease with exploring or simply looking at themselves with a compact. Most important, though, hopefully they’ll stop seeking validation in men’s approval. Because they’ll know that they are enough.

Like Madonna three decades ago, Monáe’s set a new bar for owning and extolling female sexuality. Only this time, it’s not meant to shock, objectify or ensure that the label makes its money back. It’s just for her. And you. As it should be.