As her rented SUV loops through the rocky switchbacks outside Zahlé, the largest city in central Lebanon, Sonya Iverson looks across the wide, scarred basin of the Bekaa Valley. Decades into the worst drought in nine hundred years, scrubby cedars and shoebox apartment buildings give way to a crust of farmland so dry it looks shattered. Trucks rattle through military checkpoints in plumes of fine red dust. The smell of diesel hangs in the air, and in the hazy distance, the mountains of the Syrian border rise like a plea, or a warning.

Then there are the tarps—blue and white waves of plastic tarps and razor wire that wash over the hillsides. Under those tarps live nearly four hundred thousand displaced Syrians who have fled to the Bekaa Valley since 2011, when a cruel, brutal civil war began to render their homeland unlivable. Because the Lebanese government has banned the construction of permanent camps for Syrian families, asylum seekers patch together tents and sheds wherever sympathetic landowners will rent them space, often in exchange for manual labor. Into the sea of tents, she and a few dedicated friends will carry a truckload of wooden A-frames, metal stakes, and coils of nylon webbing. Over the course of two weeks they will seek out the children of the camps, and try to teach them the sport of slacklining, a safer and sillier version of tightrope-walking popularized by rock climbers forty years ago. With her gear and her tirelessness and her smile she will help the children forget their fears—or use their fears—for a few minutes or an hour, so that their fears might be transformed into confidence.

That’s the idea, anyway.

Edith Piaf warbles on the stereo of the rented Kia a little after noon. The driver is Bradley Duling, Sonya’s partner in Crossing Lines, the nonprofit she founded in 2013. It is a small but fiercely devoted crew that lugs their gear to the places where there are no playgrounds, using the sport to build bonds among people. Bradley, who is also Sonya’s boyfriend, steers into the driveway of an indoor soccer gym on the Beirut–Damascus highway, seven miles from Syria. At the far side of the lot, across another barren field, a cluster of weary tents hides in the shade of a nearby building.

Sonya hops out of the passenger seat. She is tall, lean, and muscular, with a dark curtain of hair that falls past her elbows, and a tendency to punctuate her sentences with a trill of laughter. Her friend Beat Baggenstos slides out of the back. In 2015, Beat (Bay-at), who is thirty-five, left his job as a business manager for Deutsche Bank and the following year founded ClimbAID, a rock-climbing nonprofit for refugees and underprivileged youth. Crossing Lines and ClimbAID will combine their efforts during this trip in order to reach as much of the local shabab (youth) as possible. Beat’s team has been in Lebanon for months already, building relationships with the local shawishes, or overseers, of the settlements, whose approval is necessary for any program like this to operate. Having been given the go-ahead, the only preparation left for Sonya and Beat is to scout locations for their joint teaching sessions.

At first, this site doesn’t look promising. It is wide and flat, which is good, but chalky, bare, and unforgiving, which is not. There are no trees or boulders to use for slackline anchors, and the hard ground will not yield for stakes. The open-air building itself is held up by metal columns, but pillars are designed to bear weight vertically, not horizontally.

Furrowing her brow, cocking her head, and squinting at the piles of donated gear in the back of the Kia, Sonya’s features look like abacus beads sliding into place. Part of what slacklining has taught her is how she can best use whatever is available, even when it’s not much.

After a few silent minutes: “It looks like we’re going to have to use the truck.” She is referring to the vehicle they call The Rock, ClimbAID’s modified 1997 Volkswagen T4 Eurovan encrusted with brightly colored bouldering holds. “We’ll park the truck and use the posts.”

Bradley, an engineering consultant who considers the proper rigging of a slackline something of an art, nods his approval. Beat agrees, and, plan in place, the trio checks their phones for directions to the next site. But before they can leave, the manager of the soccer club, a paunchy older gentleman named Nasser, waves the young Westerners into his office.

The room is laced with scented tobacco smoke from a shisha pipe stationed in the corner, and a small prayer rug is neatly folded under the television. Nasser ducks behind a doorway and returns with a manhole-cover-size platter of fresh dates, bananas, and guava perched on his arm. He pours his guests glass mugs of syrupy Lebanese coffee from an enameled pot before sitting down and puffing thoughtfully on his hookah.

Nasser does not speak English, and Sonya speaks only a little Arabic, but one of Nasser’s sons happens to be doing work around the facility. Through him, Nasser explains that he wants to do what he can to help local children, some of whom live in the small settlement just a few yards away. For today he is willing to let Crossing Lines and ClimbAID use his space for free. A few awkward minutes pass with everyone nodding appreciatively, before Nasser’s face lights up with an idea. He disappears again into the back room.

There is the sound of rustling, followed by clanks, and then a sustained whoosh of loud, mechanical hissing. Sonya gets up to go check on her host, only to find Nasser at the helm of an industrial air pump, his deeply lined face peeking out from behind a zorb, an enormous plastic bubble with a person-size doughnut hole in the middle. He motions for Sonya to crawl into the bubble, which she does, and he shows her how to grip two handholds inside it to keep herself steady. Then Nasser proceeds to roll Sonya around the room and she giggles while bouncing dizzily off the walls.

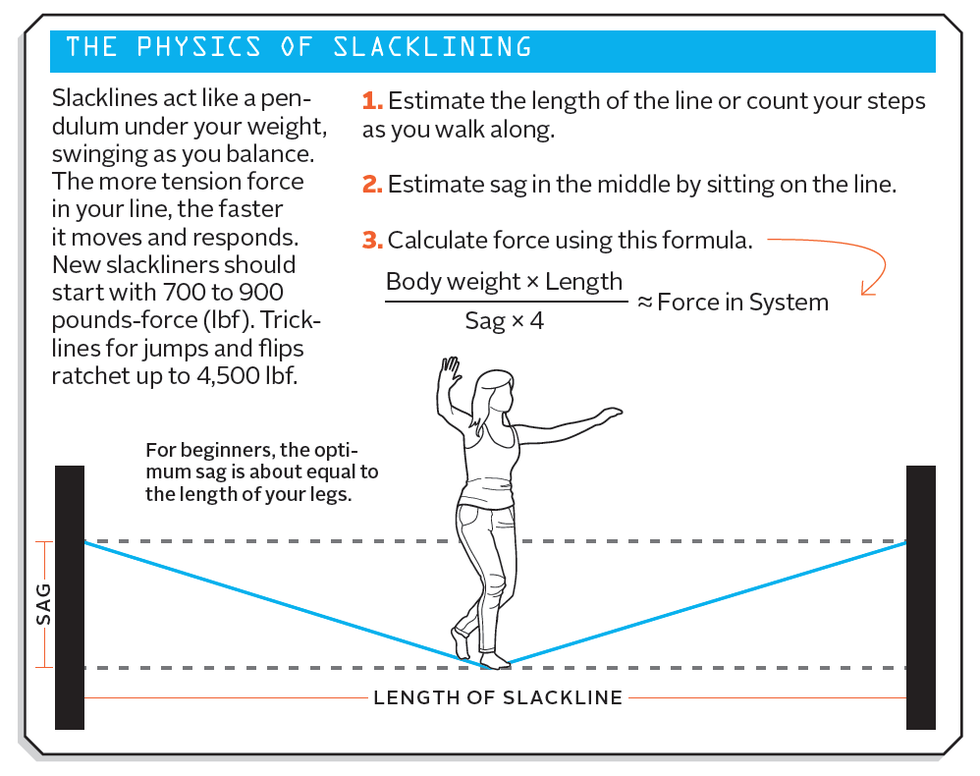

To cross a slackline—or try to—is to humble yourself before the laws of physics. Unlike tightrope walkers, who use high tensions, guy wires, and suspended weights to ensure that their steel cables move as little as possible, slackliners prefer the inherent instability of a bouncier, more flexible medium. The minute weight is put on it, the flat nylon slackline begins to move, bouncing underfoot and swinging back and forth at the same time. This freaks out the balance-loving human brain, which fights to bring the body back into equilibrium. Previously dormant leg muscles tremble or jerk to one side, creating waves in the webbing that travel down the line and back in milliseconds. A slackliner must anticipate those waves and resist the urge to amplify them. It takes weeks, months, sometimes years of practice to learn how to control your body the right way, but even the most experienced “slackers” fall all the time.

In some ways, that’s the point. If tightrope-walking, with all its sober elegance, is the classical violin, then slacklining is the country fiddle, full of mischief and improvisation. Though some do it competitively, for most enthusiasts there is nothing to summit or “win” in slacklining. The same line you crossed (or “sent”) yesterday could very well defeat you today. The aimlessness of it, the lack of scorekeeping, is part of its appeal. What’s more, it does not require fancy gear or exceptional fitness. It is a test of patience, not of strength. It is also a flawless barometer of the practitioner’s state of mind. “Fear and stress turn into muscle tension,” Sonya says, “which makes the line shake, which makes you shake, and it all comes back to you. It’s like talking to a mirror.”

Three hours after setting up in Nasser’s field, the Mediterranean sun hangs low in the sky, and the Crossing Lines team is ready to start teaching. Three twenty-foot lengths of one-inch-wide flat nylon webbing have been propped up on wooden A-frames, cinched into clove hitches, and tightened with heavy metal ratchets so that they can support weight, yet still have some give. Each line is suspended about twelve inches off the ground and radiates outward from The Rock. Encircled by color-blocked tumbling mats, the ClimbAID truck shines like a beacon in the dusty white rock-yard.

“I never know if anyone will show up,” Beat says, scratching nervously at his dark beard. The problem for him, and for Sonya, and for anyone hoping to organize diversions near the settlements is that in Lebanon, Syrian youth as young as ten are encouraged, sometimes forced, to find jobs as soon as they can physically handle them. Basic survival doesn’t leave much time for extracurriculars. “It’s very hard to plan ahead,” he says. “For these kids, there is only now. There is no tomorrow. There is no five minutes from now.”

A few minutes pass. The volunteers pace, stretch, pop their knuckles. Sonya puts up one hand to shield her eyes from the sun and then—hey, here they come! Two small boys shuffling up the drive, arm in arm. They are followed by another three, and then two more. Two sedans rumble off the road and eight teenagers spill out. In tight knots and large packs, the stream of new faces soon tops forty.

It has taken her months of planning to make the necessary contacts, scrape together the funds, recruit the volunteers, and court manufacturers for sponsorships in order to make this trip happen, and even then, Sonya worried that it wouldn’t. Many of the emails she sent seeking advice from other nonprofit groups went unanswered. Certain colleagues mistook her enthusiasm for naïveté. And right before she was set to board a plane for Beirut via Istanbul, the U.S. government suspended visa services in Turkey, and Turkey responded by refusing to allow U.S. citizens into its borders. It was a mess. But now—now, they are here.

“Aismi Sonya,” she begins, using the basic Arabic she taught herself after college using Rosetta Stone. “And this—” she reverts to English and points behind her—“is a . . . slackline.”

She climbs onto the line and sits on it cross-legged, suspended there as easily as if she were sitting down to lead story time in a classroom. Then she drives her body upward and begins gliding back and forth on the line in slow, balletic steps. With her eyes fixed straight ahead and her hands floating outward, she lunges forward like a fencer, before pivoting and swiftly balancing on one leg. From a certain angle, she seems to be hovering in midair.

The children’s mouths contract into astonished little o’s. Who is this woman, and how does she balance like this, without any help?

Sonya dismounts to urgent cries of “Ana! Ana! [Me! Me!]” as Bradley and Johan Sakr, a soft-spoken twenty-seven-year-old architect and one of Lebanon’s few slackliners, patiently sweep the kids into queues.

With Johan’s assistance, I ask some of the newcomers if any of them have tried something like this before. The boys shake their heads emphatically. Are they nervous about trying something new?

“No!” they shout in unison, flexing their biceps and making Superman poses. They wear the distinct toughness of children who are used to taking care of themselves.

An eleven-year-old boy named Yousef takes Sonya’s arm and begins his first shaky steps across the webbing. His free hand sculls the air, trying to grab onto something invisible, and he laughs hysterically at his wobbling knees. Offering her shoulder for steady support, Sonya matches the pace of his slow, hesitant feet. When Yousef reaches the end, he looks as though he has summited an Alp.

“Bravo!” Sonya shouts. She holds up her hand and Yousef slaps it.

Yousef’s friends Abdel-Rahman, Chady, and Wissam scurry over to see if they can best him. Abdel-Rahman, who is twelve, makes a pronouncement like he’s stamping a decree: “Beautiful!” As soon as he finishes his turn, he darts around to the back of the line, calling over his shoulder, “I’ll try again, but”—he jerks his chin at Sonya and Bradley—“I need someone to hold onto me.”

“Don’t worry,” Sonya calls back, her voice tumbling into that laugh. “No one crosses their first slackline!”

Even Nasser wants to try. With Bradley’s help, he hoists himself onto the line by one loafered foot and sways for a minute before cautiously stepping forward. Bradley all but carries him across, and Nasser claps his new friend on the back. “You have to understand,” Nasser says, turning to Johan, “I’m very old!” (In truth, he doesn’t look older than sixty.)

The teenage boys are the last to join. For an hour or so, the pack keeps to the perimeter, scrolling through their phones with cigarettes dangling from their lips. They have texts to send and selfies to snap, especially selfies with the female volunteers, whom the boys follow around like worshipful ducklings. But once they see their friends having a good time, they elbow their way to the front of the lines. The older kids grasp each other’s arms and help the smaller children find their balance, while others pass out glasses of tea from Nasser’s kitchen. When the sky finally fills with a bloody desert sunset, the teens flick on their cars’ headlights so that the group can keep playing. Everyone scrambles around in the sweeping wedges of brightness, silhouetted against the dark.

Like many Lebanese citizens, Johan Sakr used to be wary of refugees. For months, the country’s prime minister has decried the strain that a swelling tide of foreigners puts on the small country’s shaky electrical grid, dwindling water supplies, and anemic jobs market. But now that he is working with Syrian children up close, Johan thinks differently about the crisis. “When you see what people don’t have, it makes you appreciate what you do have,” he says, solemnly. “These kids aren’t thinking about their egos, or their shoes, or how they look to other people. They’re just . . . having fun.”

That fun can still exist in circumstances this dire seems so unlikely as to be impossible. Suicide among children in this population has been a persistent, horrifying problem. And yet here are a couple dozen kids enjoying—truly enjoying—the footloose, kinetic freedom of the moment.

I have been mostly hanging in the background, watching—the writer with the notebook. But I walk over to a seventeen-year-old named Mahmoud who is watching from the sidelines and ask, “What did you think of all this?” He crushes out a cigarette and I make a light joke about not being able to take one step on a slackline without falling off. “For you, was it hard?”

Mahmoud grins in a way that is too guarded, too old for someone his age. “For the Syrian people,” he says, “nothing is difficult.”

The next morning, on a threadbare sofa in ClimbAID’s Zahlé apartment, Sonya wriggles out of her sleeping bag, puts on her glasses, and pads down the hallway to take an icy shower. Armed with a cup of coffee, she plots the GPS coordinates of the day’s teaching session and checks a live map of Middle East conflict zones on her laptop. A dab of red shows some type of dustup in nearby Rayak, and twenty miles north, in Baalbek, a wide swath of pink indicates Hezbollah territory, but today’s section of Bekaa is generally calm.

Sonya closes her computer and begins stuffing her clothes into the 70-liter backpack she has lived out of for three years. Everything in it, from the cocktail dress she keeps on hand for unexpected party invites to the stud earring she wears to pop out her phone’s SIM card, is an artifact of her fastidious brand of self-sufficiency. “I have trouble letting other people do things,” she says into her coffee. But that is an understatement. In addition to managing her own biotech consulting company, she runs three nonprofits (Crossing Lines, Slackline U.S., and the International Slackline Association, of which she is president), and she taught herself web design to market those projects. She earned her doctorate in molecular biology and biochemistry from Boston University in 2016. She is a human Swiss Army knife of contingency plans.

“Most of what happens with these slackline projects comes from Sonya taking charge,” Bradley tells me later. He has kind eyes and a calm voice. The couple met at a highline festival in Turkey four years ago and have lived on the road together ever since. “She is so thoroughly determined to make things better for other people. But sometimes it’s quite sad. She doesn’t take any time to take care of herself. I have to put a lot of time into making sure she slows down.”

None of Sonya’s childhood friends live out of backpacks, and none of her backpacker friends travel with cocktail dresses, but something in Sonya has always rebelled against the restrictive boxes that society tends to put people in. She grew up near the Canadian border in a tiny outpost called Sunburst, Montana (population 332), where the high school didn’t teach calculus and nearly everybody, especially women, stuck close to home. Unlike the other girls in her graduating class of twenty-three students, Sonya was a science nerd who loved sports.

“I was on skates as soon as I could stand,” she says, still proud of her injury scars and the way her elbow pops when she extends it. “I spun circles on my rollerblades on the kitchen floor until I broke my arm in a bad landing. Then I did it again with the cast.”

Sonya didn’t grow up afraid of much in Sunburst, at least not until she was seventeen and 9/11 happened. It wasn’t the threat of terrorism that frightened her. It was the anti-Muslim bigotry that popped up in surprising places around her hometown. “We should just bomb them all,” she remembers a friend’s stepfather saying about the Middle East, to her confusion and horror. How could anyone want to kill millions of people he’d never met?

That encounter, and several more like it, fueled Sonya’s desire not only to travel and study the history of the Islamic world but also to help others connect with people different from themselves. “People are people everywhere,” she says. “That’s one thing I trust.”

After receiving her bachelor’s in biotechnology from Montana State University in 2007, she saved up a year and a half’s worth of bartending tips to finance a three-month solo trip to the Middle East, most of which she spent working at an agricultural research center in Aleppo, which was then the largest city in Syria. She found Syria to be a warmer, more diverse, and more cosmopolitan place than the media headlines about the country’s political tumult had led her to believe. In fact, she felt so comfortable there, she almost didn’t come back to the U.S.

Most of what she learned about confronting fear, and about herself, came afterward, when her then-boyfriend introduced her to slacklining in a Bozeman park. As a lifelong jock (swimming, baseball, volleyball, basketball, track), Sonya was surprised, even frustrated, that she could not pick up the skill easily. It took her a solid month of regular practice before she could consistently cross, or “send,” a thirty-foot-long line, and even then, every step presented a new challenge.

Not wanting to be outdone by her male friends, who were tackling longer and higher slacklines, Sonya soon decided to try the sub-specialty of highlining, which involves rigging the line across a canyon or between mountains and wearing a climbing harness on a backup line for safety. It did not go well. Gazing into a chasm south of Bozeman, she found her body literally paralyzed by fear, unable to will her legs forward. This time, no matter how much she tried, she couldn’t rationalize her feelings into nonexistence.

Sonya refused to let the instinctive terror she felt while highlining keep her from trying to improve. She reminded herself that if other people could do this (and she was seeing them do it, right in front of her), then eventually she could do it, too. But every time a thought crept into her mind, even a thought about where to place her feet, she fell. And every time she ended up dangling by her harness, her perfectionist ego was sent through a shredder.

Still, she kept trying. Sonya learned that intense focus was the best weapon for calming her body and fighting her fear. This deceptively simple practice was at its heart a form of meditation, and, like meditation, the peace she found on the slackline rippled outward. “At first, you’re focusing on muscle control, breathing, balancing,” she says. “But as you learn, you focus on how your emotions influence your body, how being angry makes it harder to walk on a slackline. Maybe you realize that if anger makes slacklining difficult, it might impact other parts of your life.”

Six months into her training, 150 feet above Montana’s Gallatin Canyon, Sonya sent her first highline and wept. All the emotions she had suppressed in order to concentrate came rushing out at once. That thin strip of nylon carried her to a new universe, one in which nothing, not even walking between mountains, seemed impossible anymore.

Sonya took herself, and life in general, both more seriously and less after that. Failures didn’t upset her as much as they used to. Stumbling was part of human growth. All that mattered was moving forward.

“You learn when to fight for control,” she says, “and when to let it go.”

On another blistering patch of concrete ringed by refugee shelters, the smell of cooking fires is mingling with exhaust fumes, and a new crop of kids are pushing their faces through the bars of a gate outside a small school. In front of them, Crossing Lines and ClimbAID have set up a colorful activity hub. The children look at it as they get closer. They may not know what it is, but they seem pretty certain it is intended for fun.

The sound of Bekaa is the sound of children: crying, laughing, calling to one another in the maze of flimsy structures that some have lived in all their lives. Over half of the refugees in Lebanon are under the age of eighteen, and the majority of them have no access to a school, let alone a playground or a park. Their voices cling to the valley the way dust clings to the skin.

Thirty-five boys and girls, most between the ages of nine and twelve, have been invited here by the staff at Sawa for Development & Aid, a Lebanese non-governmental organization that operates a resource center nearby for refugee families. One of Sawa’s primary objectives is providing counseling and other holistic services for Syrian women and children who have experienced trauma, an approach broadly known as psychosocial support. “Young people need activities to get them out of the atmosphere of the camps,” Ziad Ghneim, the programs manager at an educational nonprofit called the Sonbola Learning Center, had explained to me the day before, when Sonya and Bradley met to discuss setting up a slackline behind the center. “Very few NGOs provide games. We would love a playground, but”—he turned his palms upward apologetically—“we would need a lot of money.”

Slacklines are portable, cheap, and easy to assemble from everyday materials, which is why Sonya thinks they could be a good fit for places like Sonbola and Sawa.

“Yalla, shabab! [Come on, kids!]” a smiling Sawa staff member calls out, jangling his keys. He opens the gate, and nearly three dozen youngsters vault through, bouncing off each other like atoms, shouting “Aiwa! AIWA! [Yeah! YEAH!]” Dressed in spangled jeans and delicate silver jewelry, some of the girls resemble glittering meteors shooting across the sky. Without hesitation, they throw their arms around the Crossing Lines volunteers and plant fluttery kisses on their cheeks.

“What is your name?” the kids ask Sonya, softly rolling their r’s in polite, near-perfect English. “Where are you from?”

She answers, and a slow, rhythmic clap ignites in the crowd. “Son-ya!” the children begin chanting. “Son-ya! SON-YA!”

Sonya and Bradley both perform short demonstrations to a cresting swell of applause, Sonya with a few yoga poses and Bradley balancing on one shoulder in a half-handstand. When they finish, once again every kid wants to be first.

It is a cheery cyclone of chaos, this yard. Every child has a question, every child wants a hug, every child has a joke or a song that simply cannot wait. The boys want to play hide-and-seek; the girls want hearts and flowers drawn on their hands. One of the adults from Sawa plugs in a radio, and the kids gyrate to fizzy Lebanese pop.

Out on the slacklines, however, the rollicking vaudeville slows down, if only for short, placid pauses. Faces twist into looks of deep concentration, and bodies elongate to balance themselves. For these few hours, these kids in this small rectangle of the Bekaa Valley don’t have to think about the wreckage of their home city of Homs. Today, their minds are free to explore the world outside the barbed wire, even if their bodies can’t.

Crossing Lines’ third day in the Bekaa Valley takes them just five miles from the Syrian border to a small family settlement and school flanked on one side by a parched field and on the other by a sheep pasture. They are joined again by Johan Sakr, and also by Nassib El Khoury, thirty, the cofounder of a Lebanese capoeira school. As the ClimbAID team sets up the bouldering station, Sonya motions to the growing crowd of children and teenagers to gather round. She tells them who she is, what she’s doing here, what fun they’re about to have. At first, there are about a dozen boys and girls of all ages, but soon more flow in from neighboring settlements across the field.

The families here are having a harder time. A few of the toddlers tug on the volunteers’ shirts and mouth the word mai, tipping their thumbs back toward their throats. They are asking for water, which is too costly for the adults in this settlement to give away to kids who live down the road. With a handful of Lebanese pounds, Bradley and Johan drive to the nearest gas station and come back with as many two-gallon water jugs as they can fit in the car. The kids are notably more reserved, especially the girls, many of whom are old enough to cover their heads with hijabs. Nassib squints across the field, and sighs. “Girls of fifteen, sixteen are not expected to do sports,” he says. “They’re expected to get married. But sometimes, if you encourage them to challenge one thing, they begin to question other things, too.”

Some of them already are. In every group, there is always that one child who is just a bit more outspoken, or who asks one more question, or who pushes back a little harder against the rules, and Sonya tries to give that student more of her time. She knows what it’s like to be hemmed in by others’ narrow expectations, and she knows what it’s like to step outside of them.

At this settlement, that kid is a girl of maybe twelve who wears black polka-dotted leggings and a defiant, hands-on-hips attitude. She is a prom queen or board chairman in the making, with confidence that would strike fear in the hearts of boys on any middle-school playground in the world. She does not wait for instructions, she does not ask for permission. Instead, she narrows her eyes and sets her jaw.

The girl hops onto the line, waves away Sonya’s help, and marches ahead—only to have her legs buckle and her torso lurch forward. Her face flushes and falls. Her head jerks toward her chest. This is so much harder than it looks.

“It’s okay,” Sonya says, grasping the girl’s arm and steadying her with a soft hand on her back. “Feel the line. Hands up. Look at one point in front of you.” The girl focuses and slows, still teetering, but centered. More relaxed. She raises her head and smiles again. One foot in front of the other. Sonya dances her across to the end, giving her a high-five and down-low, then wraps her in a hug.

Sonya knows that not every child she meets will eventually make it home. Sharing the sport she loves can’t change that—or end droughts, or stop bullets, or rebuild cities—but she hopes that giving kids a few hours to explore the possibilities of their movements, she can help some of them build the confidence they’ll need to someday live a normal life.

“If all we do is give refugees food and water and a tent to live in, we haven’t solved a problem,” Sonya says. “We’re going to have a generation of kids who didn’t grow up learning how to play, didn’t grow up learning how to socialize. These kids need to feel like kids. They need opportunities and connections to the world beyond their settlements.”

By the end of the afternoon, there are foot races and backflips and somersaults and handstand contests. Several of the older girls tuck their scarves into their collars, hook their ankles onto one of the slacklines, and use it for push-ups. Another boy grabs a discarded piece of cord and turns it into a jump rope. With a few pieces of plywood and some nylon webbing, an unremarkable driveway has been transformed into its own tiny land ruled by creativity and invention, awash in dust and laughter.

This appears in the April 2018 issue.