A Long, Strange Trip

With All Things Must Pass, his documentary chronicling the epic rise and fall of Tower Records, actor-director Colin Hanks brings the story of his hometown’s most famous, freewheeling brand to life on the big screen.

It was the best of times, it was the loudest of times.

It was an eruption of youth, a climb into middle age, a collapse and slump into repose. It was short stories crafted from long memories. It was haze and booze and sideshows, a front-row seat beneath popular culture’s sprawling, messy big top. It was upheaval and downsizing, a spectacular collision of women and men and words and music. It was six decades of flying before an eternity on the ground. It was gleaming yellow and red, a legend speckled with rust. It was a name, repeated and revered and whispered and hushed.

And then it came to this—the silence filling Russ Solomon’s house.

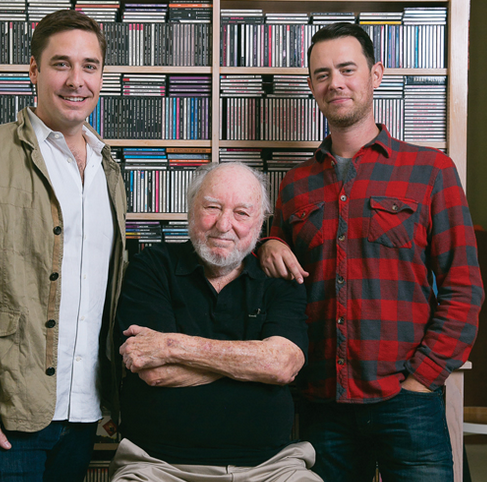

Solomon, 89, sits in his library, wordless and motionless between tales in a burnt orange chair. Thousands of books surround him from floor to ceiling, the space augmented by framed Bob Dylan lyrics, tiers of CD boxed sets, sculptures, sketches, photographs, and other artwork and ephemera. A microphone perches in a boom stand extended over his head, registering only the faint rustling of Colin Hanks reviewing papers in a chair to Solomon’s left. But Hanks, the actor-filmmaker who attended high school less than a mile from this low-slung Sierra Oaks edifice, directs a sound engineer seated on the floor behind him to stop recording. Now the microphone idles, too, while Hanks keeps his head down.

On a couch across from Solomon, Hanks’ producing partner (and fellow Sacramentan) Sean Stuart scoots toward the edge of his seat. He leans his elbows on his knees.

“That’s it?” Stuart asks.

The quiet resumes. Hanks looks up.

“Yeah, that’s it,” he says.

“Really?” Solomon asks.

“I know that’s really weird,” Hanks says.

“What’s weird is you’re weird,” Solomon jokes.

Stuart leads the way in a loud, knowing chuckle between the three of them, returning the house to a noise more in line with the empire of decibels for which Solomon is best known: Tower Records, the Sacramento-born global entertainment juggernaut that began when a teenaged Solomon commenced selling vinyl records out of his father’s drugstore on Broadway in 1941. Its ascendancy in the ’60s and ’70s both fueled and paralleled that of the music industry during the same time, when phenomena like the British Invasion and arena rock and disco burrowed into the consciousness (and wallets) of baby boomers along the West Coast. By the early ’80s, the retailer had expanded to points both east (downtown Manhattan) and Far East (the eight-story Tokyo centerpiece of a spun-off Tower chain that thrives to this day throughout Japan). By 1999, with more than 170 record and bookstores embedded in 20 countries, Tower was earning revenues of more than $1 billion annually.

By 2004, Tower had declared bankruptcy.

This fact serves as the startling epigram to All Things Must Pass, Hanks’ new documentary about Tower’s inexorable rise to worldwide prominence, swift plunge into oblivion and, finally, its enduring place in cultural mythology. Part joyride through a half-century of influence and part bittersweet record-shop postmortem, the film juxtaposes recollections from Solomon and his closest lieutenants with testimonials from high-profile customers like Sir Elton John, Bruce Springsteen, label chief David Geffen and Foo Fighters leader (and ex-Tower staffer) Dave Grohl. More than seven years after their initial interview with Solomon—and after weathering a succession of financing perils of their own—Hanks and Stuart debuted All Things Must Pass in March at the South by Southwest film festival in Austin, Texas.

Which is where the weirdness comes in, at least for Solomon. “When Colin and Sean came to see me about this in the first place, I said they were totally nuts,” he recalls. “[I asked them], ‘Who in the hell would care about something like that?’ But they persisted. So good for them. Let’s see what happens now.”

RELATED: See photos from the Sacramento premiere of All Things Must Pass

For Hanks and Stuart, the childhood friends who inaugurated their Los Angeles-based production firm Company Name with All Things Must Pass, “persisted” is one way of putting it. On the first day of shooting in 2008—at Tower Records’ former location on Watt Avenue—the camera overheated. A hit crowdfunding campaign in 2011 later triggered a fusillade of doubts from some backers who accused the beleaguered filmmakers of taking their money and running. Hanks, 37, co-starred in full seasons of three TV series—The Good Guys, Dexter and Fargo—while he and Stuart, 36, struggled to salvage their documentary labor of love. Another Russ Solomon-launched music venture—R5 Records, in the former site of Tower Records on 16th Street and Broadway—came and went before All Things Must Pass had cobbled together more than a few days’ worth of production footage. Hanks and his wife, Samantha, had two children, and Stuart and his wife, Margot, had three in the time it took the filmmakers to conceive and deliver one 100-minute movie.

When Hanks (center) and Stuart came to Solomon with the idea for All Things Must Pass, “I said they were totally nuts,” the Tower Records founder recalls. (Photo by Marc Thomas Kallweit)

So sitting with Solomon in his library last October, recording the last of the Tower mogul’s comments for All Things Must Pass, the significance of the moment—of the climactic silence just minutes away—is hardly lost on Hanks and Stuart. The end is near. First, though, some clarifications. Stuart wants to know when Solomon remembers hearing for the first time about Napster, the pioneering file-sharing service that all but nuked the music industry and record stores at the turn of the millennium. Meanwhile, Hanks has questions about Tower’s aggressive growth through the 1970s. He studies his list of Tower stores that opened in the West through that decade, beginning with the iconic Sunset Strip location in 1970, then rippling out to Seattle, San Diego and Phoenix and more than a dozen other cities before debuting in Japan in 1979. Even Solomon can’t believe that the company expanded that quickly; he reviews Hanks’ documentation for proof.

Just before wrapping production, Stuart asks Solomon for a specific line of voiceover to place over the documentary’s planned graphic of the western United States. “It helps people understand what happened between L.A. and [Tokyo], and what you guys were doing,” Stuart says. “Because it was a major expansion, and this is where you guys really—”

Solomon interrupts Stuart, cool and unbending and sharp as a hatchet blade. “If you really think I knew what the fuck I was doing,” he says, “you’re out of your mind.”

******

To the contrary, viewers of All Things Must Pass will likely come away with the certitude that Russ Solomon is nothing less than a genius. An accidental genius, perhaps—a businessman immune to the high temperatures of risk until it immolated him, or a devout believer in what he characterizes in the film as the “Tom Sawyer theory of management,” which gathered and entrusted others to “paint the fence.” Until the fence leaned and slumped and splintered apart, anyway. But still a genius nonetheless.

“The biggest thing I wanted to be able to do is make sure [the filmmakers] understood it wasn’t just me,” Solomon says. “That was important. The whole thing—the whole development of the company—was a project that was accomplished by a lot of people. Literally hundreds, when you think about it. If it wasn’t for all the things they did along the way, it would never have reached the level or scope of where it actually ended up. I kept saying over and over: It wasn’t me who did these things. I mean, I got to be the boss and all, but it was the ideas of so many people that we were able to take advantage of—which were good ideas. And as these ideas began to propagate throughout the company, that allowed the company to grow.”

Russ Solomon sold his first record out of his father’s drugstore on the ground floor of the Tower Theatre complex, pictured here in 1965. (Photo courtesy of Sean Stuart)

Solomon’s modesty about Tower Records goes back to the business’ origins as little more than a corner of his father Clayton Solomon’s drugstore on the ground floor of Sacramento’s Tower Theatre complex. The documentary unpacks some of the popular mythology around this period: As a teenager who would cut class at McClatchy High School to work at the drugstore (“I wasn’t hanging around the streets like a truant,” Solomon says. “The truant department was upset about the whole thing, but they couldn’t get too mad at me”), young Russ managed but didn’t quite launch the store’s record operation. As he witnessed his peers’ demand for buying and trading new 45 RPM singles, the existence of a larger music market in Sacramento took greater shape in his imagination. Clayton essentially spun the record section off to his son as a standalone enterprise inside the store, and overnight, with no entrepreneurial background or plan, Russ Solomon became the owner of a record-selling business he called Tower Record Mart. The enterprise closed briefly in 1960, when Solomon’s side business as a record wholesaler capsized. After borrowing $5,000 from his father to reopen a few days later, Russ Solomon and Tower were practically bulletproof. He opened an annex in Country Club Lanes in the fall of 1960, whose success gave way to Tower Records’ first official store just a few doors down Watt Avenue in 1961.

Hanks had been a fan of Tower since the days when he would buy cassette singles, his first round of CDs, and concert tickets at the empire’s outpost on 16th Street and Broadway as a kid. (“Tom Petty, Full Moon Fever tour,” Hanks says. “March 5, 1990. Lenny Kravitz opened up. That much I remember.”) Later, while attending college in Southern California, he applied for jobs at Tower stores in Santa Monica and Marina Del Rey. “I filled out my application and they said, ‘OK, thanks,’ ” he recalls. “And I saw them put it on a stack of applications.” He never heard back.

But Hanks hadn’t known about Russ Solomon’s mid-century Sacramento gambit until 2006. At the time, Hanks was living in New York City. On a walk one evening through Manhattan’s Upper West Side neighborhood, a friend visiting him from Sacramento mentioned having seen the giant “Going Out of Business” signs festooning Tower Records’ location near Lincoln Center.

“And to think it all started in the drugstore next to the Tower Theatre,” she told Hanks.

“What?” he replied.

The friend, older than Hanks, recalled to him her visits to buy records at the drugstore before Solomon transplanted the operation to its own store across the street.

Hanks was flabbergasted. “Wait a second,” he said. “You’re telling me this giant record chain started in a small drugstore?” His friend affirmed this. “Well,” Hanks said, “that’s the beginning of a documentary, and this is the end of a documentary. There’s something here.”

The idea germinated for several months until Stuart headed to New York as well to pay Hanks a visit. The two men first met while skateboarding around their East Sacramento environs as adolescents; they had remained friends through their college days and into their entertainment industry careers in Los Angeles. Stuart was working as a co-creative director and programming executive at DirecTV when, over dinner, Hanks told him about the crazy idea he had for a documentary about Tower Records. It would be neither sepia-toned nostalgia binge nor hometown navel-gaze, but rather a project that would showcase the dramatic rise and fall of a famous store where generations of Americans learned about music. And, while they were at it, tap their pride in Sacramento’s most iconic export.

Hanks knew it was a tough balance to strike. But as Sacramentans, he and Stuart also had an advantage: They could see and appreciate Tower’s unique narrative arc from their perspective at its origin. “Look,” says Hanks, referring to Solomon’s modest beginnings selling records out of his dad’s drugstore in the 1940s, “that is about as Americana as you can get.”

“It was lightning in a bottle,” Stuart says.

“And then he goes to San Francisco, and it goes from there,” Hanks continues. “Bigger cities and bigger cities, and then it’s worldwide.”

“And then the next thing you know,” Stuart says, “it’s 20 guys from Sacramento running a multinational, humongous, billion-dollar operation. I don’t think it was lost on them, and many of them said it in the interviews. There’s a common thread there for these guys—that they really did understand, looking at it in the rearview mirror, ‘It was an incredible thing that we did.’ ”

Stuart loved the idea of the documentary from the start, and in 2007, he and Hanks connected with Solomon through Tim Comstock, a friend and eventual co-executive producer who happened to share a dentist with the Tower impresario.

A six-hour introductory interview with Solomon in Sacramento further compelled Hanks and Stuart. The following summer, they approached the landlord of the abandoned Watt Avenue store, which closed in 2006 but still featured shelving, wall décor and other leftover design elements preserved in its ghostly sprawl.

The landlord agreed to let them shoot but advised the pair to hurry up: The space would be gutted within a few weeks as it transitioned to its next incarnation as a Goodwill store.

******

The first Tower Records store, which opened on Watt Avenue in 1961 (Photo courtesy of Sean Stuart)

Hanks and Stuart spent two days in July 2008 interviewing Solomon and gathering additional footage in the sweltering recesses of Tower’s Watt Avenue catacomb. It was a “shell of a place,” as Stuart remembers it—an eerie, distant remove from the decades of loud life that came before.

All Things Must Pass begins with portions of this footage, channeling the store’s “we never close” spirit from its introductory shots. The film takes its name from the title of George Harrison’s 1970 triple LP, a phrase also emblazoned on the Watt store’s marquee when it closed. The camera floats toward the open doors as if carrying the viewer through a memory portal, or possibly the retail equivalent of the Haunted Mansion at Disneyland. The inky black interior swallows the light from faint rows of white bulbs illuminated across the ceiling. Even in the shadows, it’s a sight that any of the generations of Sacramentans who shopped at this location during its run from 1961 to 2006 will recognize immediately, right before turning their memories loose in the empty aisles onscreen.

Those memories make up many of the movie’s highlights—particularly those of Tower’s executive alumni, most of whom started under Solomon as 20-somethings and gleefully climbed the corporate ladder amid riptides of partying and vice. Count on it: No other documentary in 2015 will unearth budgets with expenses like “handtruck fuel,” the staff euphemism for cocaine. On Watt Avenue, sexual trysts unfolded in the record store’s listening booths. Staffers from the adjacent Tower Books would join up with their colleagues for whatever substances helped them survive their shifts. The Tower crew’s debauchery was tolerated as long as they showed up for work, however wasted or soggy they might have been from the previous night. Drugs would get them through the mornings, and by afternoon they had initiated one happy hour after another at neighboring bars like Sam’s Hof Brau and Candlerock Lounge.

“We’d get to the store about 8 [in the morning], we’d go do a crossword puzzle and get the store ready to open at 9,” says Heidi Cotler, the former Tower Books chief who joined the store in 1965 after being rejected by Tower Records. (“If you couldn’t read, you worked at a record and video store,” she quips. “If you could read, you worked at the bookstore.”) By 3 p.m., with the drugs tapering off and the shifts changing over, it was beer time. “The 3:30’s would come on and have a drink,” Cotler explains, “and the day guys would be on their last break, and the noon-to-9 guys would have a break, and we’d all go to the bar and have three or four beers, and then we’d all go back to what we were doing.”

Russ Solomon (third from right) with the crew of Tower Records’ Stockton store on opening day in 1974 (Photo courtesy of Sean Stuart)

Such go-go hijinks became standard operating procedure for Tower, and All Things Must Pass makes the definitive case for their efficacy through extensive archival photos, footage and testimonials from the survivors. There’s rock star Dave Grohl reminiscing about the record store chain as the only place that would hire him with his long hair (at least until Kurt Cobain inducted him to play drums in Nirvana). There’s Mark Viducich, who entered Solomon’s office in Tower’s West Sacramento headquarters one Friday evening as a shipping and receiving clerk and, after chatting over some drinks, wound up running Tower’s Japanese retail operation. Near the top of the ladder was Solomon’s right-hand man Bud Martin, an unreconstructed party animal who nevertheless represented the fiscally conservative yin to Solomon’s licentious yang. Then there’s Solomon himself, who routinely confiscated the neckties of music executives during meetings and mounted them in his office like big game.

“The underlying truth is that in this period between the ’70s and ’80s, everybody in the music business was having a good time,” Solomon says. “They don’t have as good a time today. There is no music business. There’s the digital business and the people at Apple and the people [overseeing] downloads. I’m sure they’re having fun, but it’s not quite the same thing. We had a whole family of people. Record labels, distribution companies, radio, concert artists were all a great big giant family that was having a marvelous time, really. It wasn’t just the money that you made or didn’t make. It was the fun.”

Elton John, seen here shopping at Tower’s Sunset Boulevard location in 1975, is featured prominently in ‘All Things Must Pass.’ (Photo courtesy of Sean Stuart)

Customers got in on the act, too. The documentary hints at how Tower anchored its global supremacy in the restlessness of young people on the north side of Sacramento, who Cotler mentions flocked to the Watt Avenue store in the early ’60s in desperate need of a countercultural outlet. Tower’s next two stores—San Francisco in 1968, Los Angeles in 1970—galvanized an even greater cross section of consumers. Among them were once and future superstars. In the film, Bruce Springsteen describes being “shocked” by the size of Tower Records upon his first time traveling west. Archival footage of Elton John from the ’70s shows the legendary performer purposefully roaming the aisles of the Sunset store with a list of records to buy, handing off three copies of each (one for each of his houses) to an accompanying limo driver. “I can honestly say this without any exaggeration: I spent more money at Tower Records than any other human being,” Sir Elton declaims. (Somewhere on the cutting-room floor, Stuart says, there’s another clip where John insists that shopping at Tower Records was better than any sex he ever had.)

Still, even with its all-star raconteurs and glossy, globe-trotting detours, All Things Must Pass is most affecting as a testament to the crazy will of Sacramentans—to not only create the world’s most influential record store here, but also to keep it headquartered here, establishing a home on the fringes, expanding impulsively (“Don’t lose too much money on that,” Solomon said when giving his green light to the founding editors of Tower’s beloved music magazine Pulse!), and thinking nothing of making music’s biggest power brokers come to it.

“If you come from a place like Sacramento, and you’re looking to do an expansion that goes all over the country and ultimately all over the world, you get a view [of the music business] from the outside in,” Solomon says. Staying put in this region gave Tower an advantage in seeing how diverse tastes, trends and demands were shaping up beyond music’s conventional industry hubs. “If you were in Los Angeles or New York or some place like that,” he adds, “your view really ended at the city limits.”

In contrasting glimpses of the surging modern-day city with the heyday of its best-known brand, Hanks and Stuart have delivered more than just the most Sacramento movie ever made. It’s the movie that Sacramentans perhaps won’t even know they wanted until they see it—a jamboree of flintiness, a repudiation of the provincial, a mission for more.

“Anyone from Sacramento would see it and go, ‘Oh, I know exactly who these guys are,’ ” Hanks says. “And not just because it’s Russ Solomon or whoever. They know who these types of people are. I do feel there is something about coming from Sacramento. You’re just…”

Hanks pauses, then continues in a voice scorched with both exhaustion and resolve. “We’re our own kind of breed, in a way.”

******

Making movies is hard. You need luck, wits, resilience and fortitude. Insanity, while not a prerequisite, certainly helps. Making a documentary is especially hard, if only because these elements must withstand the whims of real life. There’s no script, no beginning, no end. Just to complete production—to say nothing of editing or adding music—Hanks and Stuart still needed to acquire supplemental interviews with Solomon and his inner Tower circle, archival footage and other materials from a half-century of Tower history. “In documentary filmmaking,” Hanks says, “by its very nature, you’re not 100 percent sure what people are going to say, and you’re not 100 percent sure what you’re going to get. You’re constantly building a puzzle, and the sizes and shapes are all moving and changing. And the pieces are on fire. So it takes time.”

Mostly, though, you need money. After collecting their original footage in 2008, Hanks and Stuart embarked on a hunt for funds at the start of America’s worst recession in 75 years. Months of inertia became years of stasis. All Things Must Pass looked dead in the water.

Then one day in 2011, Hanks found the crowdfunding website Kickstarter. Since launching in 2009, the site has collected almost a quarter-billion dollars for more than 16,000 movie projects by matching “creators” to “backers” who help underwrite their budgets. In return for their contributions, backers are entitled to a tiered scale of “rewards”—perhaps a T-shirt for contributing $20, a DVD for a little bit more money, premiere tickets for even more. Creators estimate delivery dates for the rewards, which routinely get held up as productions drag on—hardly an uncommon reality in the movie business, but often an inconvenient and incompatible fact of life for backers who expect timely deliveries or progress reports, even from stalled projects. With its world-famous subject, a well-known actor at its helm, desirable rewards (like limited-edition vinyl albums signed by Hanks and/or Solomon), and built-in appeal to both movie and music press, All Things Must Pass was, in theory, an ideal candidate for Kickstarter.

Top: The Tower empire, which expanded to London in 1985, spanned more than 170 stores in 20 nations by 1999. Bottom: The Tower Records store in Tokyo’s bustling Shibuya district remains open as the flagship store of Tower’s thriving Japanese chain. (Photos courtesy of Sean Stuart)

In practice, it was a blockbuster. The filmmakers received nearly double the $50,000 backing they sought, pulling in $92,025 over 45 days in the spring and summer of 2011. Social media in particular exploded with interest, including a tweet of support from a certain Oscar-winning actor-director with his own Sacramento stories: “This will make a great docu, and I’m a fan of the filmmaker!” tweeted Tom Hanks, Sacramento State’s most famous alum. (Aside from a few editorial notes along the way, Colin Hanks says, his father has no creative or financial involvement with the documentary.)

Kickstarter success can be a double-edged sword, however. After three years of struggle, Hanks and Stuart appeared to have the momentum they sought to move forward with the movie. They also had nearly 1,700 backers scattered from Sacramento to Spain to Singapore and beyond—all nursing high expectations with varying levels of impatience. In October 2011, the duo spent four days in Sacramento logging and scanning materials from Solomon’s archives, which comprised roughly 200 boxes of photographs, expansion plans, budgets, vintage advertising and documents in addition to artwork, awards, furniture, clothing and other keepsakes that the Tower founder had donated to the Center for Sacramento History.

Around the same time, the project’s first status inquiry came in from a Kickstarter backer: “Are we looking at a 2012 release date?” This was relatively benign; by mid-2012, requests for updates turned to needling annoyance or worse.

“365 days since funding. Where do we stand?” asked one backer.

“This is taking longer than even I expected. UPDATES?? anyone? anyone?” wrote another.

“Hey, thieves,” wrote yet another. “What’s up?”

Hanks was used to being second-guessed as the son of a famous actor. And as a first-time director rebuffed by numerous financiers in his and Stuart’s search for funding, he had a thick enough skin to ignore skeptics on Kickstarter. “I’m more than happy to take those hits if I can make my movie,” he says today. But even after years on TV and movie sets, the time, expense and pressure of completing All Things Must Pass compounded in ways he hadn’t expected. “There was a long time when we just didn’t have any updates,” he continues, acknowledging the no-win situation of engaging with the project’s most vocal public critics. “When you’re getting these emails first thing in the morning saying, ‘Hey, thieves, where’s the movie?’ you want to explain to them, ‘Look, here’s the deal.’ But you just can’t do that.”

Exasperation set in as Hanks and Stuart worked to shape the project in increments, stretching Kickstarter dollars along the way and taking creative inspiration where they could. One day, while shooting the TV series The Good Guys in Dallas, Hanks was surprised to observe the crew filming parts of a stunt scene with small digital SLR cameras—the kinds of light, handheld devices an amateur photographer might port around on vacation. Upon realizing that these cameras were good enough for making a network television show, Hanks says he had an epiphany: “That’s how I’m going to be able to finish this documentary. That’s going to save costs tremendously.”

And it did. Hanks, Stuart and their crew (which included Nicola Marsh, one of the cinematographers who shot the Oscar-winning 2013 documentary 20 Feet From Stardom) filmed 16 more interviews over 2013, from follow-ups with Solomon to sit-downs with Springsteen and Grohl to freewheeling chats with Tower’s executive brain trust in Sacramento. “We knew we were never going to abandon the film after we went through that Kickstarter process,” Stuart says. “We were just taking the necessary time to make what we think is a great film that people are going to enjoy. Had we just spit something out for the money we got on Kickstarter, it would have been a disservice to the film. It would be a disservice to the topic matter. It would have been a disservice to Russ Solomon. It would have been a disservice to all the guys who are in the film and to their legacy.”

After Hanks completed filming the TV series Fargo in Calgary in spring 2014 (work that earned him Emmy and Golden Globe nominations for best supporting actor), he returned to Los Angeles to edit All Things Must Pass. The Kickstarter pestering had persisted from a handful of backers, but by the end of summer, the interviews had mostly come together to

make up the documentary’s elusive beginning, middle and end. One late night, driving east from his office in Santa Monica to his home in Los Feliz, Hanks reeled with bliss. He was crossing Los Angeles, but he might as well have been crossing the finish line.

“There was no traffic,” he says. “The windows were down. The music was loud. And I was incredibly happy.”

******

The last customer at Tower Records’ location on 16th Street and Broadway enters the store on Dec. 20, 2006. (Photo by Jeremy Sykes)

The post-Tower era in America now spans a little more than eight years—slightly longer than Colin Hanks and Sean Stuart have been working on All Things Must Pass. Other coincidences link the making of the documentary to the making of Tower itself. Both enterprises battled through money shortfalls en route to their wider audiences. Both feature funky, tuneful tours through ages and genres, guided by Solomon and his merry band. Both include memorable and frequent appearances from Elton John, an inveterate patron who calls Tower’s dissolution “one of the greatest tragedies of my life.” (This, from a man who sang at Princess Diana’s funeral.) Most poignantly, both Tower and All Things Must Pass stem from the borderline quixotic visions of the three Sacramentans sitting in the house that Tower Records built, wondering what could possibly come next.

First: a big premiere. One of the higher-level Kickstarter rewards pledges two tickets to the documentary’s world premiere in Sacramento. The film’s hometown debut will have to wait a bit longer until the Sacramento International Film Festival, which runs April 25-May 3—a little more than a month after All Things Must Pass has its coming-out party on the world stage at South by Southwest in Austin.

“Where would you like to see it [shown]?” Solomon asks the filmmakers. “HBO?”

“It just depends on who wants to see it,” Stuart says—maybe a cable network, maybe a combination of online streaming and a limited theatrical release. At a private test screening the night before, friends and insiders gave them glowing notes on a rough cut. (“Thin it out structurally, and you’ll have a perfect film,” one viewer told Hanks.) The filmmakers were blown away by how much the movie “popped” on the big screen. Either way, Stuart says, whether in living rooms or theaters, a distribution deal comes down to “who’s interested, who comes to us, and who we can get in front of.” [UPDATE: All Things Must Pass was acquired by Gravitas Ventures in April for theatrical distribution this fall.]

“Our whole goal at this point,” Hanks says, “is to make the best cut of the movie that we possibly can.” From there, he adds, “Whatever the best idea is, whatever the best plan is, that also hopefully pays the best, that’s the one we go with.”

Later that afternoon, after Hanks and Stuart and the sound man and the microphone are gone, and Russ Solomon thinks it over, maybe All Things Must Pass wasn’t such a crazy idea after all. Later still, after viewing the film, he’ll even cop to enjoying it. “I thought they did a really good job,” he says. “It’s a tough thing to cram what’s essentially 68 years of history and goings-on into [100] minutes. In general, they hit the nail on the head, if you will.”

So maybe the nostalgia counts for something. Maybe what they did at Tower warrants the attention. Sure, Solomon says, nobody went there just because it was Tower. They didn’t go just for the neon or the yellow bags or to get high or drunk or laid in the listening booths. They went because of what it sounded like—the best of times, the loudest of times. Maybe people will want to be saved from all this silence.

“It’s not that far back,” Solomon says. “It’s not 100 years. But I hope [the movie] takes people back to a time when the music business was a different business than it is today. Now, whether young kids are going to give a damn about that, I don’t know. But the older people—and there are a lot of them who experienced that—I think they’ll get a kick out of just the idea that that was part of their youth. That’s what it’s really about.”