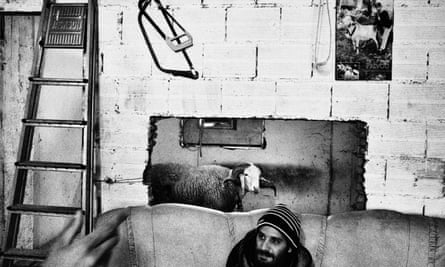

Last August in Algiers, one week before the holiday of Eid al-Adha, men in tracksuits and trainers were guarding their sheep in anticipation of the fights to come. Kbabshis, as these men are known, scour villages looking for lambs that are fast, belligerent and shock-resistant. They then spend years raising them to be champion fighters. Coaches are tough but also surprisingly tender. They treat their sheep like mistresses, stopping by the garages where they install them, bringing food, caressing and massaging them before they head out together for long walks on the beach.

Professional trainers toughen their sheep by chaining their horns to a wall: as they pull and twist to break away, the resistance thickens their sinewy necks. Unlike with cockfighting, there is no gambling on sheep fights, but speculation on the sheep market can make it a lucrative trade. Each fight lifts the value of its victor and sentences the loser to slaughter. A champion ram might fetch as much as $10,000 – although most sheep trainers on a winning streak prefer to chase glory than cash. The sheep are given names that inspire fear, like Rambo, Jaws or Lawyer. In the third round of one recent match, Hitler delivered a brutal defeat to Saddam.

Combat taa lkbech, which means sheep combat in the Algerian Arabic dialect, is a bit like football. It releases the pent-up energies of otherwise unoccupied men and allows them to safely act out potentially divisive strains of nationalism, regionalism and neighbourhood pride. But sheep fighting lacks the artistry, skill and precision that make football so enthralling: a sheep confronts an identical opponent and bludgeons him into submission using only his face. Matches are a festival of brute force and domination. When the sheep lose interest in a match, or prefer palling around with each other to smashing heads, the trainers take over, whispering and urging their beasts back into combat until they lock eyes once more and attack.

The men who train sheep for combat belong to a lost generation of Algerians, now in their 20s and 30s, moulded by an era of fear, fighting, corruption and curfews. There are few jobs and no productive roles for them to play in society. They lack relevant skills and education. Most are unmarried. They are not poor by most standards, but they depend on state subsidies that allow them to buy fuel, food and housing for next to nothing. They feel disposable, purposeless, humiliated. Most feel the future lies elsewhere. For many, that means Europe.

These young men have grown up in the shadows of two cataclysmic wars. Between 1954 and 1962, more than a million Algerian Muslims died during the war for independence from France. After almost 30 years of repressive one-party rule ended in 1991, Algeria descended into violence once again. For the next decade, a bloody conflict raged between security forces and Islamist insurgents, leaving some 200,000 Algerians dead. That period is commonly referred to as the “black decade”.

Since then, security forces have kept a stifling grip on Algeria. Both the war for independence and the violence of the 1990s helped build a powerful, revolutionary, proudly Arab-African nation-state obsessed with self-rule and suspicious of outside intentions – but also afraid of what comes from within. Beneath the outward signs of a meaningful democracy – a free press, political pluralism, resilient institutions – shadowy assemblages of business elites, ruling party figures and generals call the shots. The streets are filled with secret police and spies from the KGB-inspired intelligence agency. A curfew mentality still reigns, and there’s nothing to do after 6pm. The system and its citizens are at peace, but remain deeply wary of one another. There was no Arab spring in Algeria in 2011, partly because the memories of extreme violence in the black decade are still fresh, and secret police intercept most protests before they’ve even begun.

These days, although the Algerian capital pulses at a low intensity, beguiled by a weary calm, currents of violence still wash through it. The authorities have managed to co-opt or eliminate all major pockets of dissent, yet scarcely a week goes by without protests – localised, spontaneous micro-riots usually sparked by government policies to redistribute oil profits that favour some at the cost of others. Another common trigger for unrest is the publication of housing grant lists, since the government routinely gives out free apartments to relatives of local officials rather than low-income families who have been waiting for years. These protests purge, at least briefly, the shame of being dependent on a repressive state, enabling people to reclaim some form of agency.

Sheep fights have become a rare arena where men can escape the constant supervision of the state. While the fights are technically illegal, authorities allow followers of the sport to stream to unauthorised locations each week. Leagues in Algiers and the eastern port city of Annaba hold matches on hilltops, football pitches and school courtyards. These range from the amateurish neighbourhood fights, which draw a few hundred local men, to the grand African championship tournaments (held a few times a year in either Algeria or Tunisia – the only two entrants), which attract thousands from all over North Africa.

The Algerian government’s toleration of sheep fighting is a tacit acknowledgement that outlets for male aggression are needed. “Letting these guys have their fun reduces violence in other contexts,” said Youcef Krache, a photographer from Algiers who has spent years documenting sheep fights. “Authorities prefer they get swept up in spectacles rather than politics.”

For Fatma Oussedik, an Algerian sociologist and professor at the University of Algiers, authorities’ permissiveness towards sheep fights signals a quiet crisis besetting both masculinity and politics. “Algerian authorities have tried several methods to manage Algerian men, most recently corrupting them with oil rent. With oil prices down, there is less money and they’re more likely to have to use repressive force. Young men who have been humiliated will have to rebuild their battered masculinity. Violence is the only form of expression they have left.”

In nearly five years of living in Algiers, I had never been to El Harrach, and only knew the neighbourhood by its outlaw reputation. I had come here to meet a whisky importer who owned more than a dozen prize-fighting sheep. The man, who Krache had told me about, was famed for his colourful way of challenging other sheep trainers to a fight: “My sheep will pluck the feathers off yours like a chicken!” he would announce to rivals on Facebook. Krache told me how to find him: “Take the metro to the end of the line, El Harrach, go to the stables and ask for Banyar.”

As I left the metro, I felt the warm and familiar bustle of holiday shopping, but set in a barren post-industrial landscape. Amid potholed roads and crumbling colonial buildings, shoppers at makeshift outdoor markets were preparing for Eid. Tables set up in the streets displayed rows of gleaming knives, and sharpener carts plied their trade amid shuttered factories and ageing apartment buildings. I crossed a bridge over a dried-up riverbed through which trickled streams of chemical runoff. Beneath an overpass, piles of hay began to appear here and there amid the city detritus.

As I turned a corner, a regal-looking ram swung into sight. He was standing by a concrete wall near the overpass and had a bright red mane and a thick, muscular neck. His head was level with my ribs. He chewed thoughtfully under the watchful gaze of his trainer, oblivious as another man lowered his baby boy to swat at the beast’s broad back.

I approached and said, “Huwa chab. Ma ismu?” (“He’s beautiful. What’s his name?”)

The trainer scowled and replied: “Ebola.”

“Where is the guy named Banyar who has 13 champions?” I asked.

“He sold all his sheep and bought a Mercedes. He’s never coming back,” the trainer replied.

I wandered on until I found a space that looked like it had, until quite recently, been an electronics or dried goods shop. It was now brimming with sheep. Two men watching over them greeted me with curiosity. Sofiane was over 6ft tall, built like a water tower, with a wide belly and spindly legs. Hafid, with his bulging, veiny neck and sweet eyes set in a flat-nosed, unbreakable face, bore an uncanny resemblance to a fighting sheep. Neither appeared to notice when two young men across the street started pounding one another.

When I introduced myself as a writer researching sheep fighting, Sofiane looked faintly disturbed, and suggested it wasn’t an appropriate sport for women. “Do research on peacocks instead,” he sniffed.

Nevertheless, they led me around the corner, lifted the clattering shutters of a garage door, and took me inside. Two burly four-year-old rams rattled their chains and tried to butt at us.

The sheep belonged to Hafid. Sofiane had retired from sheep fighting five years ago. It was against Islam, he said, to be cruel to animals; sheep were for slaughter, not sport. Although he had quitit was clear he couldn’t quite leave it behind. He still lived on the margins of the sport, pouring his broad-bellied frame into the same Lacoste tracksuits and Adidas trainers as the other handlers, calling and messaging at all hours to track the ram market, and hosting kbabshis who sometimes drove 500 miles to see a match. He drew the line, though, at watching fights and raising fighters.

When a ram turns three, he is ready to fight, and his trainer shaves him and decorates him with henna. Designs range from the minimalist – a touch of red here and there – to the baroque. I once saw a sheep with a great white shark stencilled on his flank. Another was led out wearing what looked like a freshly skinned cheetah. The ram will toughen with age and experience, peaking around age seven. Lentils and long walks, Sofiane told me, were the keys to success. The ram reaches champion status when he has defeated a dozen foes. Then, the sport’s most passionate fans will tell you, the mere mention of his name instils fear across all 48 provinces of Algeria. Heated neighbourhood and regional rivalries play out on the pitch, with a particularly fierce enmity between sheep from the capital, Algiers, a latecomer to the sport, and the more established and deadly rams of Annaba, birthplace of champions and reigning capital of sheep combat.

Sofiane and Hafid started excitedly listing champions’ names: “Vagabond!” “Macro!” “Sirocco!” Sofiane caught himself and grew quiet. In the cosy garage, the mood darkened. “I wish this fighting would stop,” Sofiane muttered, looking at the floor. “I wish they would make a committee to protect these animals.”

“Oh yes,” Hafid echoed respectfully. “It should end. It’s been 40 years. We’re tired of it. They should just shut the whole thing down.”

A few weeks later, I returned to El Harrach to see a fight. Local men in long robes and Adidas were blinking in the late afternoon sun, drowsy after the Friday ritual of prayer-couscous-nap, emerging to buy baguettes and cluster at the cafes whose plastic chairs spilled out on to the street. Palm trees stood as tall as the ornate French colonial buildings that were moulting bits and pieces of decor like flesh-dripping zombies.

As I waited for Sofiane, a small van screeched by; in the back was a group of skinny young men surrounding a sheep as if they were his secret service detail. Sofiane pulled up and beckoned me into his own van, which gave off a heroic stench of sheep hormones. The scent was shrill, acrid and penetrating, and seemed to linger on my skin for hours afterwards.

He drove me a short distance to an empty lot, nudged me out, and then drove off. I entered a makeshift arena, a sandy area situated between a closed factory and a high school. Men were trickling in. They looked skittish and excited, conscious they were doing something illicit.

After a few minutes, the fighters made their grand entrances. Tyson, bleating and arrogant, was led by a man with a barrel chest. A pack of scooters zipped through the gates. Pogba, a fat, jet-black ram, panted along in their wake. Across the pitch, a sheep with a black head swayed and sprayed piss like a drunk. Messi provoked the most commotion, pompous and twitchy with blood-red hooves and a brilliant orange mane.

Around 200 spectators were gathered, milling around. I struck up a conversation with a man named Farid. He boasted about his sheep, Prisoner. “He’s worth 50m dinar” – $2,500 – “but I could never sell him. He’s like my child,” Farid said shyly, showing me pictures of Prisoner on his smartphone. Unlike most of the kbabshis I met, who were single, he also had a wife and children.

On some invisible cue, the crowd pulled forward, forming a ring in the dirt. The sheep named Lawyer entered, flashing on one flank a henna-painted Louis Vuitton logo and a 16 (the postal code for Algiers), and on the other, the crude outline of a medieval flail. Blanco, opposing him, was unadorned. The trainers massaged the animals’ flanks and horns and pulled their tails, seemingly as much to soothe their own nerves as to rouse their beasts.

Among the crowd, there was a popular favourite. “Lawyer, you’re a king!” they shouted. “This year, you’ll win it all!”

As the fight began, they fell silent. Lawyer and Blanco circled one another, locked eyes and shuffled backwards. Then they ran straight ahead and crashed into each other with full force. The crowd, enchanted, rushed forward. (Since the crowd forms the ring in which the sheep fight, they can shrink, expand or dissolve the field of battle at any time.) The referee tried to restore order among the crowd and on the pitch. The sheep edged backwards and their trainers huddled around them briefly.

Lawyer and Blanco knocked heads a few more times, half-heartedly. Each thwack rang out like a hammer striking a wall. But Blanco had begun to look bored and Lawyer was searching for a gap in the crowd through which he might wander off. It’s hard to call a match – a fight shouldn’t go above 30 hits, but there’s no clear ending, and sometimes the sheep establish which is the dominant one before the humans are ready to accept it. Farid explained that Blanco had effectively won with the first hit. Blanco’s nonchalance and Lawyer’s gentle approach towards removing himself from the scene seemed to confirm this. But Lawyer’s trainer was not ready to concede defeat.

Although there was a referee, casually dressed in denim shorts and a T-shirt, the crowd made the calls itself. Blanco’s supporters finally rushed forward, crying “Well done! Let’s go!” They rubbed his horns and kissed him on both cheeks, tore their shirts off, and danced him out through the gates and into the streets of El Harrach.

Lawyer’s trainer led him away, forlorn. I asked Farid what was going to happen to the sheep. “Ah yes. He’ll get eaten for Eid, inshallah,” he replied.

Next up was the big one: Messi v Pogba. Messi was spry and petite; Pogba looked burly but slow. The match started unpromisingly: Pogba sniffed delicately at Messi’s butt. Messi then rushed Pogba, who ran terrified out of the ring. Messi’s supporters began hollering. But Pogba’s trainers, both with scarred faces and prison tattoos, were not defeated. Grabbing a horn each, they hauled him back into the ring as he dug his hooves into the ground.

Now the sheep locked eyes and began their backwards shuffle, but this time Pogba backed up so far that he found himself among the crowd, and did his best to blend in. Hauled in once more, Pogba stared Messi down. The crowd hissed attentively. The sheep observed one another, Messi taut and focused, Pogba chewing nervously. Then Messi trotted off amiably. The crowd broke into a polite round of applause.

“They’ve stopped the match,” Farid explained. “It’s a draw. They refuse to fight one another.”

Pogba, panting so hard that his whole body shook, turned on his trainer and butted him. Without warning, Messi broke back into the ring and the two rams rushed one another once more. Another hit came, then another. “Messi! Messi! Messi!” the men chanted. The fight was called in his favour, and the crowd rushed to embrace the sheep and lift his trainer on to their shoulders.

How idealist fathers produce nihilist sons may be the stuff of Russian literature, but it’s just as true of the divide between Algeria’s ageing, visionary elites and its disaffected, disempowered youths. Since the revolution that won independence from France after 130 years of colonial rule, each decade has witnessed the arrival of a new revolutionary ideology that brought hope but ultimately failed. Waves of pan-Africanism, third-worldism and socialism in the 1960s and 70s gave way to Arabisation, political Islam and economic liberalisation in the 80s and 90s. Though meant to unite a population whose only clear shared past was a history of racial violence, these organising concepts seemed increasingly to divide – Arab v Berber, Islamist v secular, poor v rich.

The dashed ideals of each successive revolution helps explain why Algeria today is so gloomy, and shuttered against new ideas. Frustrated energy seems to be channelled into rijla (machismo). Men who work part-time, if at all, splay across the benches and borders of public squares on hot afternoons, leering at any woman who walks by. Cafes, bars, streets and mosques are all male spaces. Those in power are known as “les moustaches”; any accomplishment elicits a congratulatory “les hommes!” (“men!”). Algeria’s most emblematic and beloved film is Merzak Allouache’s Omar Gatlato (1977), the story of a young bureaucrat who is alienated and obsessed with his own masculinity. The title refers to the expression gatlato el rijla – machismo killed him.

Thirty years ago, the Algerian people embarked on their own Arab spring. In 1988, faced with authoritarianism and a crumbling economy, they boldly gathered in the streets to demand freedoms, much as Syrians, Libyans, Egyptians and Tunisians did in 2011. After Islamists won the first round of the country’s first multi-party elections in 1991, the military cancelled the results and took power. This set the stage for a fight for the territory and soul of the country, which pitted Islamist militants against security forces and lasted for 10 years. By the end of the “black decade”, the Algerian people, whose protests had opened the floodgates, were weary and just wanted peace. They had been subdued by the bloodlust of militants and the brutality of a military regime willing to do terrifying things to regain control.

In the early 2000s, Algerians came out of their thwarted revolution in a fog, generally preferring to move on and forget, rather than dig up the recent past. Abdelaziz Bouteflika was elected president in 1999 on a peacebuilding platform, and used an amnesty law to close the 10-year chapter of civil violence. Large numbers of militants took advantage of the amnesty and repented with no repercussions. Critics warned it would amount to amnesia.

As luck would have it for Bouteflika, oil prices began to rise around the same time, climbing from an annual average of under $30 per barrel in 2003 to over $100 in 2008. Oil and gas account for 96% of Algerian exports. The state, flush with cash and repressed guilt over the traumas its citizens experienced in the 90s, handed out petrodollars to assuage lingering anxieties with free housing and interest-free loans. Violence receded from city streets, and the children who survived the years of terror grew into reserved adults with a social safety net, who believed that their families’ food, healthcare and educational needs would be met regardless of skill or employment. So, in 2011, as jubilation at the fall of old regimes raced across a stunned Arab world, Algerians looked on with wariness. Things will only get worse, they insisted, painting a prescient tableau of dashed hopes, foreign meddling and an orgy of blood.

Yet by 2014, when Bouteflika ran for a fourth presidential term, the cautious optimism of the previous decade had been replaced by fatalism and despair. Oil prices collapsed that year and the crash suddenly revealed the Algerian economy’s vulnerabilities: an overdependence on hydrocarbons and an inability to produce anything domestically. Bouteflika was determined to remain in power, despite a serious stroke that had left him unable to address the nation or make state visits. Playing on domestic fears of civil war like those tearing apart Syria and Libya, he campaigned on a ticket of security and stability. Political opposition was frail and disorganised. Bouteflika was re-elected with 82% of the vote.

Today, the promises of postwar Algeria lie unfulfilled. Daily life has become an endless sequence of demeaning interactions with a bloated and oppressive bureaucracy. An outdated, socialist-inspired system rewards loyalty and promotes mediocrity while obstructing innovation and individual talent. (A popular saying here to describe the dangers of initiative and success goes “Any heads sticking out? Cut them off.”) “I pity our society because it lives in fear and in failure,” the novelist Rachid Boudjedra recently wrote.

The immense challenges faced by Algerians who wish even to discuss how to bring about change are visible, in miniature, in the literary world. Boudjedra – an original thinker, avowed atheist and provocateur, and one of the rare writers who stayed and survived the black decade – has recently been sparring with another famous Algerian author, Kamel Daoud. Daoud has been a darling of the Western media since the publication of his 2013 novel, The Meursault Investigation. A retelling of Albert Camus’ The Stranger from an Arab perspective, the novel won France’s Prix Goncourt, the country’s highest literary prize.

Both Boudjedra and Daoud wish to diagnose and rehabilitate an Algerian national identity, but they are more or less at war over how to carve out an intellectual space within which to do so. For many Algerians, Daoud has made a fatal trade-off – writing for foreign readers has won him success abroad and contempt at home. In February 2016, Daoud wrote an article for the New York Times and Le Monde, blaming the alleged assaults on hundreds of western women by migrants in Cologne on New Year’s Eve on a viral “sexual misery” of Algeria in particular, and the Arab world more broadly. Playing up the repressiveness in Algeria – couples couldn’t stroll in gardens, he claimed (falsely) – Daoud went on to state that: “People in the west are discovering, with anxiety and fear that sex in the Muslim world is sick, and that the disease is spreading to their own lands.”

Daoud’s column, even to his admirers, uncomfortably echoed the anti-immigrant, anti-Muslim sentiment that had led much of the media to exaggerate the scale of the attacks in Cologne. French and North African intellectuals condemned his argument as an example of the urge to re-educate the “savage refugee”. Boudjedra dismisses arguments such as Daoud’s as “trafficked history” – the product of an inferiority complex in a people still struggling to emerge from the psychological bonds of colonisation.

Boudjedra, meanwhile, is relatively unknown abroad and highly regarded at home. Yet he is also harassed by the very society he seeks to reflect and develop. His latest rage-filled tract, History Traffickers, published by Editions Frantz Fanon in 2017, was derided in the Algerian press for a number of historical and factual inaccuracies. More seriously, last summer, masked men kidnapped him and his wife and forced him to say the Muslim profession of faith on television. The incident, it turned out, was a shockingly cruel prank: the kidnappers were a candid camera crew from the state-run Ennahar television TV station. This stunt occurred shortly after Boudjedra had described himself as an atheist on another TV station, and the timing suggests that what was presented as a “joke” was retaliation for having made this admission. (The incident provoked a furious reaction: one journalist wrote on Facebook that it was “an insult to all of the intellectuals in this country, to all the men and women in media, to Algeria, its revolution and its history” – and the director of the channel later apologised for the episode.)

I suggested to Oussedik, the sociologist, that Algerians seemed to be a revolutionary people living in a time when no revolution seems possible. “Yes,” she said, “We are smothered. When there is a head that stands out, they either cut it off or push him out. So there are not even any intellectuals to express this. No one to embody a revolt.”

A few weeks after Eid, the retired sheep trainer Sofiane and I drove to Annaba, the sheep fighting capital of Algeria, for the national championship. (As with the earlier match in El Harrach, Sofiane, maintaining his abstinence from sheep combat, planned to wander off just before the fighting began.) Each year, a few weeks after Eid, men throng from all over Algeria for the prestigious event, which crowns the winner of a year-long championship with a trophy made of golden cups. A town of 200,000 on the Mediterranean coast near the border with Tunisia, Annaba is a key departure point for migrants – nearly all of them young men – who set out to cross the Mediterranean in inflatable dinghies.

I felt relieved when Sofiane picked me up in a roomy French sedan rather than the Chevrolet he used to transport sheep. We left the congested streets of Algiers and headed east on the East-West highway, a new, super-smooth speedway funded by the government and built by the Chinese. Dubbed the world’s most expensive road, its budget was originally slated to be $7bn but it ended up costing $13bn once kickbacks and inflated contracts were factored in. The highway stretches 688 miles across the length of Algeria, without a single crossing for pedestrians.

“Algeria is beautiful, but Algerians are lazy,” Sofiane mused as we breezed through rolling hills and olive groves, verdant against a brilliant blue sky. At the side of the road, men sold apples and dates. “Algerians don’t want to work. The French were the ones who built Algeria,” he said. I was surprised to hear him say this. His father and uncle were moudjahids – revolutionaries – who fought the French for the country’s independence. Of his 12 brothers and sisters, Sofiane alone remained in Algeria to look after his ageing parents. Having renounced his life as a kbabshi, his profound empathy for animals now found expression in his collection of caged birds.

“I used to be a pitiless fighter,” Sofiane told me. In the black decade, he was a teenager in one of Algiers’ roughest neighbourhoods. Several of his friends were killed, and he saw terrible violence – civilians murdered, babies with their throats slit. During the breakdown of law and order, he became – in his telling – a streetfighter who set out to right wrongs and defend the defenceless. Later, Sofiane showed me his scars. One stretched across the back of his head like a huge fish hook. There was a stab wound in his stomach and a small, hard knot on the flesh of his leg, where he had been shot.

In 2003, Sofiane went to jail after he stabbed a man he had seen beating his own mother. When he was released, he repudiated violence, because he realised the disenfranchised were fighting each other. “Each of us was doing injustice to one another,” he told me. “All of us were poor. I felt bad.” Soon after leaving prison, he discovered sheep fighting and became a disciple.

I grew very quiet in the car, thinking about how the war for independence – a fight for freedom and equality that inspired countless liberation movements and set the bar impossibly high for future generations – had given way to the nihilistic self-destruction of the 1990s. Instead of building the country and developing its potential, the men of Sofiane’s generation, born free but growing up in the shadows of war, had spent their formative years knifing one another.

But Sofiane lightened and began to croon, mixing raï folk music with a hymn to fighting sheep: “Bring me to Miami, I want to see Guantánamo, Hannah champion!” he sang sweetly. He could careen from the tragic to the comic, the carnal to the ascetic – later, at dinner, while wolfing down four steaks, he told me he fasted every Monday and Thursday.

Arriving in Annaba the next morning, we paid a visit to the reigning champion sheep in what used to be the Jewish quarter. Half a dozen men in athletic attire were leaning against the wall, olive-skinned and overfed, tense with their efforts to look hard. The sheep’s owner, Ala, was a short, thickset man with green eyes. A cigarette dangled from the side of his mouth as he hauled open the garage door to reveal his magnificent prizefighter, La Dope. Like its owner, the sheep was thickset and close shaven. His hooves, knees and head were painted red with henna. Ala led the sheep out on a leash. La Dope began greedily lapping at an espresso someone offered him. Another man offered him a cigarette. He gobbled it down. On special occasions, his owner said, La Dope liked beer.

Ala was so stressed that he hadn’t slept for three nights – his other sheep, El Hadj (Pilgrim), was in a championship match that afternoon. A few hours later, Sofiane and I met Ala and El Hadj at the outdoor pitch, a sandy lot with two football goals near an abandoned factory. We had to park half a mile away because the whole street was lined with double- and triple-parked cars. Ala looked queasy. El Hadj, on the other hand, perfectly relaxed, sucked reflectively on his underbite.

The lot was unkempt and illicit, like the arena in El Harrach, but there were far more spectators. Men were massed as far as the eye could see, perched atop walls, sitting on cars and trucks, balanced on the goalposts. Some had brought their pet caged birds with them. (Algerian men sometimes like to keep caged birds, and carry the cages out for walks on a sunny spring day, or set the cage on a car outside so the bird can breathe new air and hear new sounds.) A few brought a daughter or niece. As we stood around waiting, word suddenly spread that the organisers had cancelled the match. There had been some problem with the organisation. The league had booked too many matches, and afraid of an outbreak of chaos, had cancelled the whole thing.

We were beginning to disperse when a commotion broke out at the far edge of the crowd. It wasn’t clear what had started it. All the tension and anticipation, all the fear and adrenaline that the men had been holding in snapped like an overstretched band. The whole herd of men began to run all at once. Sofiane grabbed me and we sprinted to the car.

On the way back to Algiers, Sofiane was quiet, and angry that the match – which he, having forsworn sheep fighting, wouldn’t have watched anyway – had been cancelled. He was upset that the organisation that ran the league wasn’t what it used to be. Eventually, he began talking again, telling me about how the greatest joy he ever experienced was when his sheep Black Jet won a regional championship in 2007.

Sofiane couldn’t explain precisely why he had renounced sheep fighting. “I wasted my life,” he said of his days raising champions. “I’m full of regrets.” His reasons were vaguely religious, but as I understood it, he had reverted to principle, in a very Algerian – which is to say idealistic – way. He could no longer ignore that his fun was a form of idolatry, a stand-in battle where a real one was needed. He takes pleasure now from the caged birds he collects. He loves their song. They sing and are trapped, just like him.

Some names have been changed