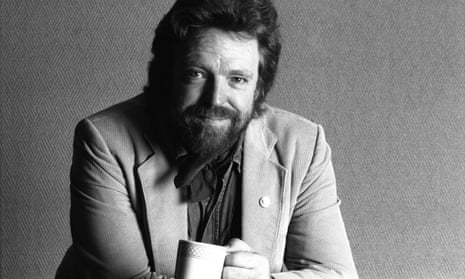

Anyone with a passing acquaintance with the Grateful Dead will know that the central songwriting partnership was that of Jerry Garcia and lyricist Robert Hunter. But there was another enduring team that fed into the band’s vision of an alternative America – rhythm guitarist Bob Weir and his old school friend John Perry Barlow, whose death, aged 70, has just been announced.

Much of the focus on Barlow in death notices has been on his standing as a libertarian champion of free speech on the web – he set up the hugely influential Electronic Frontier Foundation in 1990 having been (along with many other Deadheads) an early convert to the possibilities of the electronic bulletin board The Well. Yet the songs he wrote with Weir were the fruit of a long connection with the San Francisco band.

It’s true that, for many fans of the Dead, some of Weir and Barlow’s songs do not reach the highs of the classic Garcia/Hunter canon. But the pair paradoxically provided many of the band’s best-loved tunes, from the plaintive country lament Looks Like Rain to Weather Report Suite, an intricate, jazz-tinged paean to the eternal rhythm of the seasons.

Weir and Barlow first came across each other as pupils at a high school that catered for “difficult” children – Weir because of his dyslexia and rebelliousness, Barlow because of a wild streak that his Wyoming state senator father couldn’t handle. The pair instantly bonded. “We were easily the most unpopular kids in the school,” Barlow was to recall. When Weir was kicked out, Barlow “thought it was a miscarriage of justice” that they didn’t boot him out too, so quit in protest.

Five years later, and 1967 found the pair living in the notorious Grateful Dead house at 710 Ashbury Street, Weir playing rhythm guitar in the band and dosing himself weekly with LSD, Barlow more of an observer of a scene that was about as far removed from his ranching background as it’s possible to imagine.

Yet it was a shared love of cowboy culture that was to cement the partnership a few years later, when Weir needed lyrics for tunes he was pulling together for his first solo album, 1972’s Ace. Barlow drew on his rural roots for songs such as Mexicali Blues and Black-Throated Wind, but the pick of the bunch remains Cassidy, a song written about the daughter of a member of the Grateful Dead family but which juxtaposes that new life with the ghost of Neal Cassady, the Beat figure who had such a profound influence on the Dead, and the young Weir in particular, before his death in 1968.

Further songs followed in the mid-70s and showed how Barlow had honed his craft. There’s the demented firebrand preacher of Estimated Prophet, a song that lent itself to some of Weir’s most memorable stage moments and provided a lolloping groove for the band to stretch out on. Perhaps his best-loved words, however, belong to a song on the 1975 Blues for Allah album, The Music Never Stopped. For all its self-consciousness, it revels in the Dead’s unique status as “a band beyond description”: “A rainbow full of sound / It’s fireworks, calliopes and clowns”. And it glories in a joyful, timeless rural America: “Well, the cool breeze came on Tuesday / And the corn’s a bumper crop / And the fields are full of dancin’ / Full of singin’ and romancin’ / But the music never stopped.”

Barlow never considered himself as in the same ballpark as Robert Hunter, saying it was “both humiliating and humbling trying to operate in his shadow all these years”. As, one by one, the remaining members of the band and their extended family check out, it’s with sadness that fans say, in the closing lines of Cassidy: “Fare thee well now / Let your life proceed by its own design / Nothing to tell now, let the words be yours, I’m done with mine.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion