Shortly after 11 p.m. on a warm Saturday in September 2016, 22-year-old Nathan Carman and his mother, Linda, untied their boat, the Chicken Pox, and set out for a night of fishing. They motored south through a salt-marsh pond off Narragansett Bay, past clapboard beach houses, lobster shacks, and rust-worn fishing trawlers, all painted by the light of a full moon. When they reached the edge of the inlet, they slipped through a narrow breachway into open water, and the Chicken Pox’s 300-horsepower engine roared to life. Minutes later, the candy-colored lights of the Rhode Island shoreline faded behind them.

Before leaving, Linda had texted a family friend that she and Nathan would be back by morning. But when they hadn’t returned by Sunday evening, the friend alerted the Coast Guard. Ships, helicopters, and planes immediately began scouring 82,000 square miles of ocean but found no sign of them. Around the docks and on maritime message boards, New England boaters shared theories about what had happened. Had the Chicken Pox collided with some unsurveyed shoal? Or suffered a catastrophic hull failure? Or encountered a massive rogue wave? People who had seen the boat before Nathan and Linda left said it was in good shape, and it was equipped with an emergency transmitter that could send a distress signal and location directly to the Coast Guard. How, in the age of GPS, had a vessel like the Chicken Pox vanished without a trace?

On Friday, five days after Nathan and Linda went missing, the Coast Guard called off its search. If the Chicken Pox had gone down, the window of survivability in the North Atlantic, even in the relatively warm month of September, had all but closed.

Then, on Sunday, a crew member walking along the deck of the Orient Lucky, a hulking freighter sailing 115 miles south of Martha’s Vineyard, spotted a red raft bobbing in the water off the ship’s bow. Standing in the raft, waving his arms to catch the crew’s attention, was Nathan.

Once aboard the Orient Lucky, Nathan radioed the Coast Guard an account of what had happened. “Mom and I — two people, myself and my mom — were fishing at Block Canyon, and there was a funny noise in the engine compartment,” he said in a flat, dispassionate tone. “I looked and saw a lot of water … I was bringing one of the safety bags forward, the boat just dropped out from under my feet. When I saw the life raft, I did not see my mom. Have you found her?” Later, after a brief rest, Nathan stood on the deck of the freighter, staring out across the ocean for more than two hours. “I got the feeling he was looking for his mother,” the captain of the ship told the Hartford Courant.

Nathan’s rescue, after seven days at sea, defied all odds. But to some, his story didn’t add up. Why hadn’t he activated his emergency transmitter? Why hadn’t the Coast Guard found a single piece of wreckage? Most important: Why hadn’t Linda made it to the raft? “This story is starting to smell like week-old mackerel,” one fisherman wrote on a message board. Linda’s three sisters were among the suspicious. For years, Nathan had displayed troubling, often hostile behavior toward his mother, screaming at her over the slightest provocation. Plus, there was no overlooking the fact that, with Linda dead, Nathan stood to inherit at least $7 million of the family’s wealth.

A week after Nathan’s rescue, law enforcement from five states, along with the Coast Guard and FBI, convened to discuss Linda’s disappearance. Nathan, who refused to cooperate with the authorities, proved difficult to investigate. He lived alone in a white Colonial house in southern Vermont, and agents had a hard time finding anyone who had spoken with him for more than a minute or two. Without the Chicken Pox or Linda’s body, many believed that the most her sisters could hope for was a charge of reckless endangerment.

Then, in July 2017, with prospects of a criminal prosecution dimming, Linda’s sisters filed a “slayer action” against Nathan in civil court, where the burden of proof is lower and circumstantial evidence holds more weight. Slayer actions are intended to uphold a simple principle: Heirs should not benefit from their own wrongdoing. A man who kills his mother, for example, shouldn’t be entitled to an inheritance. But while the slayer action the sisters filed against Nathan raised questions about Linda’s death, it stopped short of accusing him of murdering his mother. Instead, the sisters accused Nathan of murdering another family member: his grandfather.

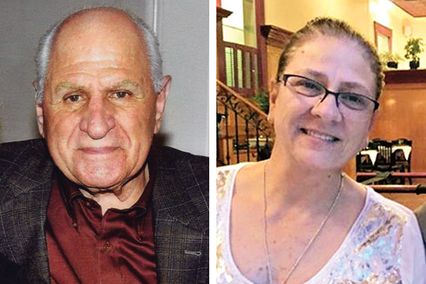

Two days after his rescue, as Nathan landed in Boston Harbor aboard the Orient Lucky, the Hartford Courant reported that he had been a suspect in the 2013 murder of John Chakalos, an 87-year-old real-estate developer worth an estimated $44 million. With Chakalos’s murder still unsolved, a murder-for-profit narrative emerged: Nathan must have killed his grandfather and mother to fast-track his inheritance. It is the kind of uncomplicated motive that network dramas are built on — but as investigators in both cases have discovered, few questions raised about Nathan yield a simple answer.

Nathan is tall and gaunt. He dresses almost exclusively in outdoor gear — galoshes, hunter-orange vests, khaki shirts — as if always ready for a turkey hunt. A patchy beard, acne scars, and a clumsy haircut obscure an otherwise handsome face. He rarely smiles or laughs, according to people who know him. As a child, Nathan was diagnosed with Asperger’s, a high-functioning variation of what is now known more generally as autism spectrum disorder. Like many people with Asperger’s, Nathan displayed above-average intelligence, consistently earning high honors in high school. But those who knew him said he had the social aptitude of a child.

With the help of psychiatrists and occupational therapists, Nathan learned to make his way through the world. Though he wasn’t very verbal and his fine motor skills seemed underdeveloped, he liked numbers and planning. He played soccer and basketball, and while he preferred the company of adults to that of kids his own age, his strongest emotional attachments were to animals. As a teenager, Nathan developed a particularly strong bond with a white Irish Sport horse named Cruise that his grandfather bought for him.

Chakalos doted on his grandkids — his motto was “Without family, you’ve got nothing.” Born to Greek immigrants in New Hampshire in 1926, he served as a paratrooper in World War II, earning a reputation as a tough guy who volunteered for the most dangerous missions. People who knew Chakalos described him to me as “ruthless” and “a pain in the ass.” After some fits and starts as a young entrepreneur, he built his fortune developing convalescent homes in the 1960s.

Chakalos married his high-school sweetheart, Rita, and settled in Windsor, Connecticut, where they raised four daughters in a modest yellow ranch house on a dead-end street. John, who was proud of his humble roots, preferred to donate his money rather than spoil his children. Though he eventually splurged on a mansion on 82 acres in New Hampshire, he and Rita kept the split-level home in Windsor for the next 50 years.

Chakalos did provide for his daughters, even into their adulthood. He paid their expenses and gave them annual allowances worth tens of thousands of dollars. But sometimes he used the money as a form of leverage — especially with Linda, the family’s rabble-rouser. In the early 1990s, when Linda was living in California, Chakalos offered to buy her and her husband, Clark Carman, a Dunkin’ Donuts franchise if they would move home. After they returned, Chakalos reneged on his offer. But he kept them nearby, installing them in a house he provided for them in Middletown, a leafy college town on the banks of the Connecticut River.

At Middletown High School, faculty and former classmates described Nathan as a loner, a six-foot-three giant running down the hallways from class to class in oversize galoshes. Teased and bullied, he mostly ignored the taunts. But he could also be off-putting. He aggressively challenged teachers and students whenever he felt they were wrong. “He was very insistent that he was right, and that was it,” one of Nathan’s classmates told me. “He would knock stuff over or whatever off the desk. The teacher would try to go out and talk to him, but there was no reasoning with Nathan.” In history, his conservative politics came through. “He was very passionate about the Second Amendment,” said another classmate. “He believed U.S. citizens should be allowed to buy any form of weapons, including rocket launchers, automatic weapons, grenades.”

Nathan grew up mostly with his mother. His parents divorced when he was young, and he and Linda often traveled together — Greece, the Caribbean, an RV trip through Alaska. Once, during a fishing trip in the Canadian wilderness, their canoe flipped over and they were forced to swim to shore. By all accounts, Linda was a giver, volunteering in the community and serving as an aide for other families who had kids with autism. But by the time Nathan got to high school, their relationship had become strained. He was prone to tantrums when things didn’t go his way — he once threw a tray of cookies at a wall after Linda burned them. “Soon enough he’s going to slit your throat while you’re sleeping” her boyfriend at the time warned her. On Halloween in 2009, a parent of a trick-or-treater called the police because Nathan had been handing out “tricks”: Ziploc bags filled with fish guts. The following year, when he insisted on moving out of the house, Linda offered a compromise. She allowed him to live in an RV parked in the driveway — far enough to appease Nathan but close enough for her to watch over him.

Whatever fragile peace Linda was able to maintain with Nathan was shattered a few weeks before Christmas in 2010 when his horse, Cruise, died of colic. The loss of a pet — one of the central pillars of his support structure — was something that Nathan was emotionally ill-equipped to handle. “The only friend he had was his horse,” Clark later recalled. “Things went downhill from that point on.”

After Cruise died, Nathan was despondent. He stopped talking to Linda, communicating with her only through handwritten notes. Plans to scatter Cruise’s ashes had to be put off because Nathan experienced what Linda described on a mental-health message board as a “psychotic episode” at school. Nathan, she wrote, had called the vice-principal “Satan” and his secretary “an agent of the devil” — the sort of behavior, she said, that was “previously reserved for me.” There was something more than autism at work, she feared. Nathan was suddenly having “paranoid delusions” and espousing “religious idiocy.”

Such symptoms are not characteristic of autism. “You don’t expect to see a sudden change in mental status,” said Dr. Jeremy Veenstra-VanderWeele, a specialist in pediatric autism at Columbia University Medical Center. “You don’t expect to see paranoia, you don’t expect to see delusions, hallucination. You don’t expect to see mood disorders, depression. When it happens, it means there’s something else going on.”

Following the incident at school, Nathan was committed to Mount Sinai Rehabilitation Hospital in Hartford. He blamed his mother for his confinement, refusing to see her. But he spent hours visiting with his grandparents John and Rita, who brought him candy, newspapers, and a radio for his room. By that point, John and Linda were locked in a simmering battle for control of Nathan, and Linda grew convinced that her father was using her son’s hospitalization to gain the upper hand. “His grandfather has insisted for 17 years that my son belongs to HIM and all his problems are the result of me, his mother,” Linda wrote on the message board. “This man (his grandfather) is allowed to sit with him in his room, behind closed doors, unmonitored for 5 hours at a time.”

Chakalos had always lavished attention on Nathan, his firstborn grandson. As a teenager, Nathan visited his grandfather at least once a week, and Chakalos brought him on errands, proudly introducing the shy, awkward boy to people around town. Twice, Chakalos donated a new engine to the local fire department, and both gifts included the same demand: that the new truck bear a plaque saying the donation had been made in his grandson’s name. He bought Nathan a pickup truck and gave him access to $400,000 in a joint bank account. It was as if Chakalos, himself a brusque man short on social grace, understood Nathan’s rigidity better than anyone. “John was very black-and-white,” Clark told me. “Almost like people with Asperger’s.”

Chakalos couldn’t understand why Linda was constantly broke, given the generous support he provided. Her life, by all accounts, was in disarray. She couldn’t hold a steady job, and her house always looked like it had been hit by a tornado. “She had a few problems,” recalled an ex-boyfriend. “She was depressed, and she liked to go to casinos.” Gambling was Linda’s guilty pleasure, a way to anesthetize herself. Sometimes all she needed was a day at nearby Mohegan Sun, but at least once she flew to Mississippi for a ten-day gambling trip. According to someone close to Chakalos, Linda had drained at least one trust fund her father had set up for Nathan. To prevent it from happening again, Chakalos created a new trust fund and put Linda’s youngest sister, Valerie, in charge.

Two days after Linda posted her concerns on the mental-health message board, a family meeting was called in the hospital’s waiting room. “Linda felt her father was butting into what she was trying to do with Nathan,” Clark recalled. “So there was some resentment.” The conversation turned to finances, and Chakalos offered Clark, who was unemployed, a job. When Clark refused, Chakalos threatened to cut off his support for Linda and Nathan. Things quickly turned violent. Linda claimed it started when Chakalos pushed her. Chakalos, in turn, accused Linda of punching, scratching, and kicking him when he tried to leave the room. Two people told me she grabbed her father by the testicles. “My father is worth $300 million, and I want my share,” Linda told police after the incident. “He is not going to cut me off. I need the money.”

Linda was arrested for assault on an elderly person, but the charges were dropped a few months later at Chakalos’s request. Clark described the incident as perfectly normal for the two. “They seemed to enjoy the animosity,” he said. “Every gathering, Thanksgiving, Greek Easter, there’d always be something like that. Then they’d move on.”

Things only got worse after Nathan was released from the hospital. According to a police report, doctors determined “that he wasn’t psychotic nor schizophrenic.” At first, Nathan hunkered down in his RV. He left every morning at 8 a.m. to visit the library or go fishing, always returning in the early evening. Living conditions in the RV soon became intolerable, and Linda, desperate for help, called a social-services hotline. When a case manager sent police to do a well-being check on Nathan, he was infuriated. Two days later, he got up early and, with a fishing rod poking out of his bag, rode his bicycle to the bus station. When he didn’t return that night, Linda filed a missing-person report. The next day, she received a two-page letter in the mail from Nathan saying he’d run away. He blamed everyone he was closest to except his grandfather.

His parents hired a private investigator, who used dogs to track Nathan’s scent and a helicopter to scan wooded areas. Police checked Nathan’s computer for clues but turned up only searches for motorcycles and pornography. Four days after he went missing, a sheriff’s deputy in Sussex County, Virginia, found Nathan loitering outside a convenience store. He had a moped, $4,244 in cash, two photos of himself and Cruise, and a plastic bag containing hair from Cruise’s mane.

Back at home, Nathan grew even more isolated. Feeling unwelcome at his old school, he fulfilled his remaining credits on his own. He rarely left his RV and urinated in water bottles. Every night, wild sounds emanated from the camper. “It sounded like he was taking a baseball bat to the inside of the place, just wrecking it and taking it apart limb from limb,” one neighbor recalled. The outbursts continued for weeks.

In the fall of 2011, terrified of what might happen when their son turned 18 that January, Linda and Clark decided to take drastic action: They signed over guardianship of Nathan to a behavioral-correction camp. Late one night, men from the camp arrived and took Nathan from the familiar surroundings of his RV to the wilderness of Idaho. Among medical experts, such “boot camps” are widely considered to be harmful to children on the autism spectrum, imposing rigid expectations that a teenager with Asperger’s would find incredibly difficult to meet. But when Nathan returned a few months later, things seemed to improve. Days before his 18th birthday, he started classes at Central Connecticut State University. He moved out of the RV and into a cousin’s house. He began helping his grandfather with his business, and Chakalos paid for Nathan to move into his own apartment. The two discussed plans for Nathan to move to New Hampshire and live full time at his grandfather’s weekend mansion. “His grandfather was proud of him,” someone close to Chakalos told me. “Nathan had already switched his license plate to New Hampshire.”

Then, in the fall of 2013, the relative stability in Nathan’s life came to an abrupt end. That November, his grandmother died of lung cancer at the age of 84, and Chakalos slipped into a deep depression. “He didn’t want to live anymore without Rita,” one of his friends told me.

A little before 8:30 a.m. on Friday, December 20, less than a month after Rita’s death, John’s eldest daughter, Elaine, went to check on her father at his house in Windsor. She found Chakalos dead in his bed, shot three times in the head and back. There was no sign of forced entry. Nothing had been stolen, and the murderer had taken care to pick up the bullet-shell casings before leaving the crime scene.

According to police, Nathan was the last person to see his grandfather alive. They’d had dinner together the night before, but Nathan was unable to account for his whereabouts later that evening. Linda told investigators that she and Nathan had been scheduled to drive to Rhode Island to go fishing around 3 a.m. She had waited in her car for her son in Glastonbury, about halfway between Windsor and Middletown, but he never showed up. Unable to reach him, Linda went home. She didn’t hear from Nathan until 4 a.m., when he called to say he was in Glastonbury waiting for her. She met up with her son and, as police collected evidence at the crime scene, Linda and Nathan spent the morning fishing.

The investigation surfaced a complex web of family secrets. Police sought to obtain the phone records of at least 11 persons of interest. Linda was considered a suspect, which wasn’t a surprise given her assault charge against Chakalos, her gambling habit, and the fact that, like her three sisters, she stood to inherit millions. Police also learned that Chakalos’s longtime bookkeeper had skimmed more than $400,000 from his boss, a crime for which he was sentenced to three and a half years in prison.

Linda and her sisters all passed a polygraph test, but Nathan refused to cooperate with investigators. When police searched his apartment seven months after his grandfather’s murder, they found a gun locker in his bedroom closet with a Remington shotgun and a pellet gun, neither of which was linked to the murder. But the next day, they got their biggest break in the case: Before his grandfather was killed, they discovered, Nathan had purchased a Sig Sauer Patrol 716 assault rifle, which was the same caliber as the gun used to kill Chakalos. When police asked Nathan why he hadn’t told them about the assault rifle, he said he’d forgotten about it. When they asked him where it was, he said he’d lost it.

“That gun is a high-end, $3,000, semi-automatic assault weapon,” said Dan Small, an attorney for Nathan’s aunts. “How do you forget about a weapon like that when the police are asking you about guns? More importantly, how do you lose it? Did you leave it at the Dunkin’ Donuts?”

In Nathan’s apartment, investigators found handwritten notes with details about “self-propelled Improvised Explosive Devices” and “sniper rifles on an aerial video stabilizing platform.” Neighbors told police Nathan was “a time bomb waiting to go off,” referring to him as “murder boy.” There is no evidence linking Asperger’s with violence. Some researchers, however, believe that autistic traits, in conjunction with psychotic symptoms, can contribute to the disinhibition that precipitates predatory aggression. To avoid misinterpreting Nathan’s autism as evidence of “deceit or avoidance,” police consulted S. David Bernstein, a forensic psychologist. If Nathan had committed the crime, Bernstein said, he would have researched it on his computer, likely returning to the same websites over and over to check his work. But any hopes of catching Nathan planning the crime were dashed when investigators discovered that he had discarded his computer’s hard drive.

Local police had little experience handling murder cases, and one detective was later demoted for mishandling critical evidence. But the biggest obstacle was something simpler: A prosecutor can’t build a case around a missing hard drive or a gun that disappeared. Despite the hole in his alibi on the night of the murder, there simply wasn’t enough evidence to arrest Nathan, much less convict him beyond a reasonable doubt.

The motive was as elusive as the evidence. Why would Nathan kill the person in his life who seemed to understand him best and who supported him in his quest for independence? “John was the most important thing to Nathan,” said Clark. “At times I think he felt he was his father more than me.” Nathan’s parents weren’t the only ones who believed in his innocence. “Unlike his mother, I never saw Nathan arguing with John,” a source close to Chakalos told me. “There were periods of time back when he was younger that Nathan didn’t even want to talk to his grandfather. But once he turned about 14 or so, I don’t recall any time they’d argue about anything.”

It is unclear when Nathan’s aunts began to suspect him of the murder. Though they fought from time to time, Linda was close to her sisters. Valerie, as the trustee of Nathan’s trust fund, approved a check for nearly $200,000 to pay a top criminal-defense attorney to represent him. Long after their father’s murder had been relegated to the state attorney’s cold-case squad, the sisters continued to pay for billboards around Hartford advertising a $250,000 reward for information leading to an arrest in the case. If the Chakalos sisters did suspect Nathan of killing their father, they didn’t discuss it outside the family. They rarely speak to the media and declined multiple interview requests for this story. But on the anniversary of their father’s murder, while Linda was still alive, Valerie made a vague and chilling public statement. “This person has gotten away with murder,” she warned, “and chances are it will happen again.”

Like the first step into a massive saltwater swimming pool, the continental shelf off the Atlantic coast extends some 100 miles out to sea, where, along a ridge line, the ocean floor plunges from a few hundred feet to more than a mile deep.

Submarine canyons striate that ridge line, forming perfect habitats for game fish like bigeye tuna and marlin. Accordingly, the canyons are the preferred hunting grounds for adventurous, well-heeled sport fishers. Nathan longed to fish the canyons, but Linda, his only fishing partner, reportedly refused to join him. No one goes that far out without an experienced captain and a capable boat.

In December 2015, Nathan purchased the Chicken Pox, a sturdy 31-foot Down-easter, from a metalworker in Massachusetts who had retrofitted the vessel’s topside with a stainless-steel deck and pilothouse. Six months later, he bought tuna-fishing gear from a fisherman named Shawn Sakaske. After talking to Nathan for an hour about fishing, Sakaske worried that the 22-year-old wasn’t experienced enough to venture that far from shore. “He just wasn’t ready for the canyons,” Sakaske recalled. “He had no one to teach him.”

Sakaske wasn’t the only one who felt that Nathan was too inexperienced. An employee at Ram Point Marina told me that he once spent an hour helping Nathan back the Chicken Pox into its slip and, on multiple occasions, had to explain basic concepts of boat maintenance. But Nathan liked to tinker with the boat as if he were a seasoned pro. The day he and Linda set out on their fateful trip, Nathan removed the Chicken Pox’s “trim tabs,” two foot-long paddles mounted on the back of the hull. There was no reason to remove the paddles, which act like rudders to regulate a boat’s pitch and tilt as it cuts through water at high speeds, but Nathan felt they “were serving no purpose.” Removing the trim tabs left half-dollar-size holes in the boat’s hull near the waterline, so Nathan filled them with marine putty. As an employee at West Marine, the boating franchise where Nathan bought the putty, said to me, “You wouldn’t believe the dumb shit people do to their boats.”

Linda, who had turned 54 earlier that week, looked forward to her fishing trips with Nathan. Boats had long served as floating DMZs in their embattled relationship. That night, before shoving off, she texted a “float plan” to a friend, a standard precaution she took whenever going out on a boat. She and Nathan, she told her friend, would be fishing near Block Island — nowhere near the canyons — and would be back Sunday morning. “Call me 12 noon if you don’t hear from me,” she wrote.

Soon after Linda sent her float plan, she and Nathan were under way, heading through the salt-marsh pond and past the breachway into open water. In a legal dispute with his boat-insurance company, Nathan claimed that he and his mother fished near Block Island for an hour or so. Then, around 3 a.m., they headed to Block Canyon, arriving shortly after dawn on Sunday. Weather conditions were good and the sea was calm. They dropped their fishing lines and spent the next five hours trolling for tuna before things went terribly wrong.

Nathan heard a sound coming from under the deck. When he opened a hatch to check it out, he found the compartment filling with water. According to tests done by the insurance company, it’s likely that the marine putty Nathan used to fill the holes in the hull had failed and that the boat had been slowly taking on water for hours. Nathan said he told Linda to bring in the fishing lines and started making preparations to jump ship. He went into the boat’s pilothouse a number of times but never sent a distress signal. Then, as he told the Coast Guard, “the boat just dropped out from under my feet.” Nathan’s $4,000 life raft — mounted on top of the pilothouse and fully stocked with packets of water, crackers, and survival gear — would have self-inflated the second it hit water. At some point, Nathan said, he managed to transfer additional survival supplies from the Chicken Pox to the life raft and clamber into it. He began blowing a safety whistle and calling out to his mother, but she was nowhere to be seen.

Crimes at sea are notoriously impenetrable. Evidence is usually limited to the weather, the tides, and any cell-phone or GPS data that has been relayed to shore. What’s left resembles the narrative that Nathan provided in the murder of his grandfather: a gap-toothed story that raises more questions than it answers. One charter-boat captain doubted that Linda would have agreed to a long trip to the canyons aboard a boat that didn’t have a toilet. Her ex-boyfriend asked how Nathan could have swum to his life raft while wearing his signature galoshes. Some keen observers wondered why Nathan instructed his mother to reel in the tuna lines if he planned to abandon ship.

As mysterious as the Chicken Pox’s sinking was, investigators were equally perplexed by what happened after the boat went down. The Coast Guard launched a massive search-and-rescue mission but saw no sign of Nathan. “He was found in the search area,” a spokesperson said after his rescue. “Why didn’t he see us? Why didn’t we see him?”

According to Nathan’s timeline, he spent a full seven days at sea on his life raft. Yet the captain of the Orient Lucky said Nathan was neither dehydrated nor hypothermic when he was found. Skeptics who watched video footage of Nathan’s rescue wondered why he looked relatively healthy after spending a week on a raft little bigger than a doghouse. Survival experts — including one I spoke with who spent 76 days aboard a life raft after his boat sank — say surviving such a mishap at sea isn’t impossible, but they would have expected Nathan to look much worse after his ordeal.

The issue of where Nathan was found only deepens the mystery. The Orient Lucky pulled him out of the water in the vicinity of Alvin Canyon, some 35 miles east of where the Chicken Pox supposedly went down in Block Canyon. According to Glen Gawarkiewicz, a research scientist who studies the continental shelf for the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, currents over the shelf flow east to west — which means Nathan should have drifted in the opposite direction. With no way to locate the Chicken Pox, investigators had very little to go on. Once again, as in the case of his grandfather’s murder, Nathan had lost the one piece of evidence that could have helped determine his innocence — or guilt.

Since his mother’s disappearance, Nathan has become something of a celebrity in gothic New England, and everyone seems to have a theory of the case. Some are plausible (Nathan didn’t know what he was doing or where he was when the boat went down). Others are creative (Nathan killed his mother, sank the Chicken Pox, and then hid on another boat until shortly before his “rescue”). Still others are far-fetched (Nathan and Linda planned the whole thing, and she is now living on the lam in the Caribbean). Sakaske, who sold Nathan the tuna gear, thinks Linda was ensnared in the fishing lines. “When the boat sinks from under her and goes straight down, everything in her feet is now tangled and all that stuff is hooked to the boat and she didn’t have a knife on her,” he said. “She panics and tries to take a breath and sucks in saltwater and drowns.” Clark shared a similar theory with me. “There’s not a bone in me that thinks Nathan could have killed his mother,” he said. “Maybe he did something to the boat, but that’s a mistake.”

Implicit in many of the theories is the assumption that Nathan meticulously planned to execute his mother. Absent from those theories, however, is a reason why Nathan would choose a plan that involved putting himself at such risk. Sinking a boat 100 miles offshore and expecting somebody to happen upon you defies logic. The only way Nathan could have reduced that risk, while avoiding detection by the Coast Guard, would have been to dump his mother’s body and hide out for seven days. There are no islands that far out to sea, but it’s conceivable he could have hidden somewhere along the coast, 100 miles away from the canyons, and then returned to sink his boat once a freight ship was nearby. If Nathan did kill his mother, it seems more likely that he did so in a fit of anger. Maybe Linda had refused to go to the canyons. Maybe she brought up her father’s murder. Or maybe Nathan blamed his mother for his grandfather’s death.

Six weeks after his rescue, Nathan held a memorial service for Linda at a church in Hartford. He brought a bouquet of pink lilies and, afterward, he sheepishly pushed his way through a scrum of reporters with his head down. “The whole family was invited,” he said, getting into his pickup truck. Conspicuously absent from the service were Linda’s sisters. Still, according to someone close to the family, they continued talking to Nathan. On the phone, he seemed not to hear the anger and fear in their voices. It must have come as a shock to him last summer when he learned that his aunts had filed the slayer action against him in court. “It’s clear that there are holes not just in Nathan’s boat, but in Nathan’s story,” said an attorney for the sisters.

Since his rescue, Nathan has given very few interviews, and he declined to speak to me. Last year, during a rare television appearance, he accused investigators of targeting him because of his disorder — Asperger’s, he said, made him “the lowest hanging fruit.” He categorically denies any involvement in the deaths of his grandfather and mother. Today, nearly a year and a half after Nathan was rescued, investigators seem no closer to solving the mystery. Nathan lives by himself in a house in Vernon, Vermont, that he bought with money his grandfather gave him. Everyone in town knows of the quiet recluse. He spent months renovating his home, adding two more stories and transforming it into a bizarre four-story eyesore. Building materials are strewn around his yard, and a handwritten sign staked at the end of the driveway politely wards off reporters.

The slayer case has only just begun in probate court, and Linda’s sisters have said that if they win, they will donate Nathan’s inheritance to charity. Above all, the lawsuit seems to be a last-ditch effort to surface the whole truth about what happened to their sister and father. For now, they are left with Nathan’s version of Linda’s final moments: going down with the Chicken Pox, her son on a life raft only a few feet away, yet impossible to reach.

*This article appears in the January 22, 2018, issue of New York Magazine.

*This article has been updated to reflect that Nathan and Linda did not, in fact, cancel their fishing trip the morning Chakalos’s body was discovered.