The Mr. Olympia bodybuilding contest, which has been held in Las Vegas since 1999, and the Arnold Classic, held annually in Columbus, Ohio, since its inception in 1989, constitute the fall and spring formals, respectively, for the bodybuilding community. Both events crown bodybuilding champions, but the Olympia is the older and more prestigious of the two. Since 1965, when a handsome, tanned Mormon named Larry Scott wowed a small but dedicated crowd with his twenty-inch “tape-measure” biceps, the Olympia has fulfilled founder Joe Weider’s dream of crowning the “champion of champions” among the heavily muscled set.

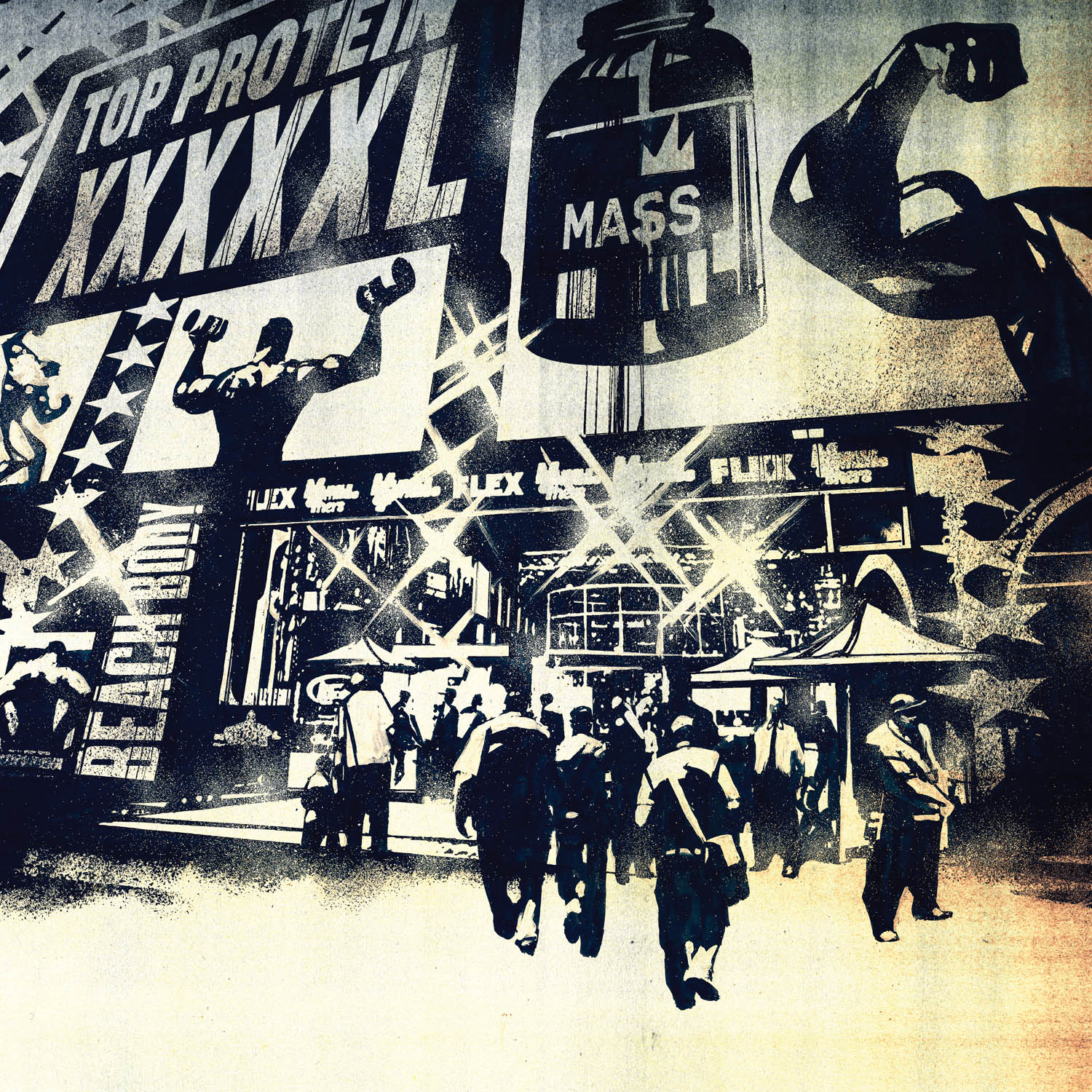

In the fall of 2016, this championship of champions and the fitness exposition with which it was combined sprawled across 500,000 square feet in the Las Vegas Convention Center, welcoming 1,100 vendors and exhibitors, a new high for the event. More than 55,000 men and women (another milestone) roamed the vast space, most clad in muscle-baring finery, in Zubaz pants that billowed around their quads and spaghetti-strap tank tops that clung to their lats. Many attendees looked like they could be competing in the Olympia finals themselves. They were bodybuilders, after a fashion, united by a common vision of better bodies through chemistry. They were packed in and giddy, these large people carrying large bags of nutritional supplements from booth to booth. Respite could only be found outside in the 100 degree heat or at the convention center’s cafeteria, where they could eat grilled-chicken salads and discuss the impressive bodies they had seen and the muscle-building supplies they had purchased.

There, at a table with filmmaker Chris Bell, retired World Wrestling Entertainment (WWE) pro wrestler Matthew Wiese, and Wiese’s bodyguard, Tony, a conversation was taking place, which, like so many other conversations that would take place over the weekend, was primarily about drugs.

Bell, an ex-powerlifting champion who directed the 2008 steroid documentary Bigger Stronger Faster*, had just returned from a rally in Washington, DC, where thousands of aggrieved users of an herbal supplement called kratom were petitioning against the federal government’s decision to classify it as a controlled substance. According to its proponents, kratom aids with opioid withdrawal, eases musculoskeletal pain, and increases energy, although so far no clinical tests have been carried out that substantiate these claims.

Gaining access to steroids and other related drugs can be challenging, but disciples of steroid culture, like cannabis enthusiasts, have found both legal and illegal ways to secure their fix, through licensed physicians prescribing human growth hormone (HGH) and testosterone replacements (which are rarely covered by health insurance) or more casual connections at the gym, or on the dark web, or on steroid forums like Reddit’s “Steroid Source Talk” board, where the drugs are usually cheaper and far more ubiquitous (though poor quality is always a risk).

Wiese, who wrestled for World Championship Wrestling as a catchphrase-spouting monster named Horshu (working the sound “shu” into nearly everything he said) and for the WWE as one half of a powerhouse tag team under the moniker Luther Reigns (who partnered with the even larger Mark Jindrak), had come to Las Vegas with the intention of buying as much kratom as possible. Tony was Wiese’s added muscle, which seemed superfluous since Wiese himself is six-four and around 280 pounds, and Tony is eight inches shorter and at least forty pounds lighter.

“I’ve taken good stuff and bad stuff all my life, and this kratom is good stuff,” Tony said. “I mean, I sold crack in South Central, and you don’t get anywhere with that. But kratom, you take it and you’re, you know, just woken up. Like a cup of coffee but sharper.”

Wiese tapped me on the forearm to draw my attention. “I got all kinds of problems,” he said, referring to the various cognitive and physical impairments that prompted him to join a class action lawsuit against the WWE (the suit was dismissed in March 2016). “I’m not a scientist, but I know what works. My chronic pain, it’s way reduced. I don’t feel any desire to take tramadol or oxycodone.”

Bell, who has spent the past fifteen years researching the supplement industry, nodded. “When something appears to be efficacious, the government response is always, ‘Let’s regulate this. Let’s put this behind a pharmaceutical paywall. Let’s make people who have learned what does and doesn’t work, which is how people have always learned stuff, jump through all these hoops.’ ”

“My whole life has revolved around my body,” Wiese added. “You look around here, and it’s all these people who clearly understand their bodies. I’ve landed flat on my back, taken body slams, fallen off the ring apron. I get it; my body gets it.”

“I started taking steroids when I was forty,” interjected Tony, whose current age was indeterminate. “How old do I look now?”

No one answered.

“I’m forty-nine,” he continued. “Do I look forty-nine?”

“All this stuff works like a charm,” Wiese said. “But look, Tony and I have to run.”

The two stood up—the towering pro wrestler and his five-eight bodyguard—and bused their trays.

“They’re going to see their dealer and load up on kratom,” Bell explained. “Lots of people are here to see their dealers and get what they need. The Olympia is a kind of body-building prom.”

“Actually, the term bodybuilder is very specific and refers—or should refer—to someone who is training for the sport of bodybuilding, not to someone who lifts weights in a gym,” says Anthony Roberts, a fitness writer whose obsessiveness over precise nomenclature informs his book Anabolic Steroids: Ultimate Research Guide. That book was one of the first comprehensive treatments on the subject since Dan Duchaine’s Underground Steroid Handbook began circulating within the beefcake literature during the early 1980s. Since then, Roberts has reported on fitness, nutrition, and the byzantine workings of the Food and Drug Administration—which determines the legality of supplements and drugs that are used for building strength—for a variety of American and European outlets, many of them part of the so-called “muscle press” that caters to the interests of a niche set of readers.

“That said, you look around at a convention like the Olympia, and you see all of these guys who are bound together by a particular style of training, of diet, and, in most cases, of performance-enhancing-drug consumption. It’s a culture in which people have learned from one another, as was the case with all those baseball players José Canseco introduced to steroids during the 1980s.”

In an age of widespread public contempt for steroid use, usually directed at athletes in high profile sports such as professional baseball and mixed martial arts, bodybuilding represents an outlier: Its highest-profile competitors are not just performance-enhanced but almost superhumanly so. The only thing about the modern iteration of the sport that isn’t enhanced is the replica of legendary 1940s physique star Eugen Sandow’s body that graces the Mr. Olympia trophy—though even that rendition looks slightly more beefy than photographs of the man suggest.

“The bodybuilders today are huge because the testing is absolutely minimal,” Roberts says. “The point everybody misses—the point that’s been missed in every story about something like the Olympia, which is usually about what a freak show it is—is that steroids created bodybuilding as we know it.”

“So it’s like rave culture and ecstasy, how one complements the other?” I asked.

“If you mean raves existing as an outgrowth of the ecstasy experience, as something you can experience while in that altered state, then yes,” he answered. “Bodybuilding isn’t a ‘steroid sport’; bodybuilding is the official sport of the steroid lifestyle. And this lifestyle follows what is almost like a Roman agricultural-festival cycle: A lot of the people who attend the Arnold in the spring and the Olympia in the fall train just like the bodybuilders they’re going to see, bulking and fertilizing their bodies in the winter for the summer harvest. Many dream of nothing more than being mistaken for one of those dudes at an event—mistaken for being a pro—and, in between, they’ve got great bodies for going to the Jersey Shore or wherever. The Olympia, for everything else it might be—a place where there are weightlifting competitions, where vendors sell superfoods—is first and foremost a steroid convention with a bodybuilding show.”

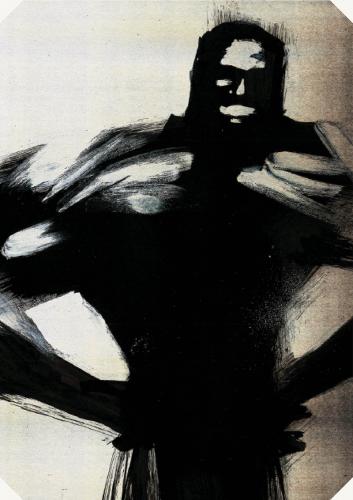

The goal of that bodybuilding show, in any case, is the discovery of muscular perfection. While speaking to fans on a stage in the rear of the convention center at this year’s show, former Mr. Olympia champion Jay Cutler, a five-nine man almost too wide in the shoulders to fit through standard doorways, told a self-deprecating story about how a mother and daughter saw him returning to his car and mocked his waddling gait. Cutler, though proud of his accomplishments, recognized that these had nothing to do with the desirability of his body. After all, he was in the business of maintaining the perfect body, not an attractive one.

Surely this was the hypertrophied, body-beautiful future Joe Weider had been dreaming of when he began collating and stapling together the pages of pictorial physique magazines, with guides to developing broader shoulders and thicker biceps. Weider, who along with his younger brother, Ben, carved out a fitness-publishing empire in the 1940s from the basement of his parents’ house, chafed against the strictures of the Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) and the Mr. America bodybuilding contest it sanctioned. At the time, the AAU was dominated by an erstwhile US Olympic weightlifting coach named Bob Hoffman, a lanky curmudgeon who insisted that his bodybuilders meet various strength prereq-

uisites before being allowed to compete.

Weider had enjoyed some success as a bodybuilder but far less as a weightlifter, and vehemently disagreed with the AAU rules that Hoffman had helped draft. Requiring that a bodybuilder shoulder-press 200 pounds, for instance—something that Weider struggled and, at times, failed to do—made little sense in the context of what was essentially an aesthetic contest. Moreover, Weider argued that Hoffman was unfairly overlooking African American athletes with impressive physiques, citing Melvin Wells’s failure to claim the Mr. America crown on several prior occasions. During the late 1950s and early 1960s, Weider would attempt to remedy these oversights by using his publications to promote the careers of black bodybuilders such as Rick Wayne, Harold Poole, and Chris Dickerson. But for Weider, racial equality came second to aesthetics: He was willing to consider anyone as a possible champion, so long as they had the look he prized.

For Weider, the point of a bodybuilding contest was to recognize well-built bodies. Previous Mr. America winners such as 1944 champion Steve Stanko, a prodigiously strong Olympic athlete who won the title despite suffering from bulbous varicose veins caused by phlebitis in his legs, didn’t fit the body-beautiful mold. In Weider’s opinion, bodybuilders should train as he believed the Greeks had: first for perfect bodily symmetry, and then in more specialized ways for competitive sports like wrestling. Train for form, in other words, and function would follow.

The dispute between Weider and Hoffman intensified throughout the 1940s and 1950s, until Weider finally launched Mr. Olympia, in 1965. Unlike other bodybuilding pageants, such as Mr. America, which limited winners to a single title, Mr. Olympia was an invitation-only affair for individuals who had already won championships. It would leave no doubt about who was the world’s most perfectly developed man. This idea of perfection would be further driven home with the 1977 debut of the Eugen Sandow trophy, a statuette invoking the legacy of the Prussian strongman who wowed Victorian-era crowds with his gorgeous physique.

The initial Mr. Olympia, at which Larry Scott prevailed, was a modest affair. Scott defeated Harold Poole, an African American, and Earl Maynard, a native of Barbados. Scott defended his title in 1966, then retired. Sergio Oliva, an Afro Cuban weightlifter with musculature of heretofore unseen proportions, claimed the next three Olympias, establishing a pattern that holds to the present: The “champion of champions” was a dynastic position, with upsets unlikely and one-off victories rare.

Oliva’s reign ended with the emergence of Arnold Schwarzenegger, the charismatic “Austrian Oak” who, while perhaps not as physically gifted as his predecessor, exceeded him as a vehicle for selling Joe Weider-published magazines and Weider-brand supplements. Weider might have been more racially inclusive than Bob Hoffman and the AAU, but his pageant was still a bottom-line enterprise: He needed a champion with a great body and an even better personality to help him move his products, and, during the 1970s, the racist attitudes of white readers ensured that black bodybuilders did not sell copies the way white bodybuilders like Schwarzenegger did.

In the course of winning six consecutive Olympias (and one more, after returning from a hiatus) and starring in George Butler’s hit documentary Pumping Iron, Schwarzenegger exceeded Weider’s wildest expectations. By the time he had become a cinematic superhero, mainstream awareness of bodybuilding had increased considerably. Or so it seemed, in the neon spandex-and-leg-warmer era of aerobics and bodybuilding-style weight training that followed Schwarzenegger’s ascension to superstardom.

Much as it did when it debuted in the 1960s, Mr. Olympia owes the very shape of its competitors to the performance-enhancing drugs they take. As these drugs improved and evolved over the years, so, too, did the competitors. Sergio Oliva and Arnold Schwarzenegger were once supernatural poster boys for state-of-the-art pharmaceuticals—chemicals that became professional sports’ signature influence as well as its dirty little secret—and yet, not that many years later, despite the improbability of those bodies, the heroes on posters these days are flexing considerably larger muscles.

The Olympia debuted at an auspicious moment in the history of American steroid use, just seven years after Ciba Pharmaceuticals released the oral steroid Dianabol, in 1958, making it the first such drug to hit the domestic market. In short order, Olympic training tables, NFL locker rooms, and the country’s handful of high-performance bodybuilding gyms were awash in these substances. Powerlifters sported shirts that read “Dianabol: The Breakfast of Champions”; Olympic weightlifter Ken Patera told reporters that an upcoming competition against the Soviet Vasily Alekseyev would determine “which are better—his steroids or mine.”

The 1960s and 1970s represented a Wild West period in the history of performance-enhancing drugs. The federal government wouldn’t move to classify steroids as controlled substances until the late 1980s, when Joe Biden pushed a major legislative overhaul through the Senate. Prior to that, sports dynasts, such as Schwarzenegger and many of the star players on the Pittsburgh Steelers, used the drugs to dominate their respective fields. But for the world that surrounded bodybuilding and powerlifting, even a federal crackdown proved unavailing. Classifying steroids as Schedule III controlled substances might have changed how the lay public viewed these drugs, but diehards weren’t about to give them up. It was in the strength-training and bodybuilding communities that steroid use had become most widespread; and it was in these communities, even after suspected users in other sports began to face official opprobrium, that the folk science of performance enhancement would continue to develop.

One can trace the chemical evolution of the sport from Larry Scott, the smooth-bodied winner of the first Olympia, to Lee Haney, the densely muscled eight-time champion who dominated the 1980s, claiming every title from 1984 to 1991. During this span, competitors downplayed the negative cosmetic side effects of the available steroids, such as bloating and acne. Tanning sprays minimized the visibility of pimples and pustules while highlighting the body’s overall definition, and an improved understanding of diet and diuretics controlled the bloating that accompanied some of the heaviest-duty medications. Former chemistry teacher Frank Zane, who claimed the trophy at three Olympias starting in 1977, brought a new level of precision to drug dosages and timing. Meanwhile, workout fanatics Tom Platz and Mike Mentzer used steroids to push their exercise regimens beyond the outer limits of human possibility.

Haney, a 245-pound piece of mobile Greek statuary, appeared to represent the end point of human muscular development. “Everybody thought Haney was as good as it could get—that he was Schwarzenegger 2.0,” Chris Bell said. “When we were growing up, his smiling face and his awesome biceps were inescapable. He was on every Weider magazine cover.” But then a cheaper, synthetic version of HGH, a substance which had been around for a while but was prohibitively expensive, entered the marketplace. “And suddenly you had a guy like Dorian Yates from England.”

Yates, who started his career as a slight teenager pumping iron in a grimy Birmingham gym, combined easier access to HGH with Mike Mentzer’s high-intensity training routines in order to win his first Olympia, in 1992, at a lean 260 pounds. “Yates was just huge,” Bell said, “and maybe he wasn’t as aesthetically pleasing or symmetrical in his development as Lee Haney, who he almost beat in 1991, but there was nobody like him. He had shoulders and deltoids that were like big boulders.”

“Yates is a great example of this phenomenon of how drugs shape bodybuilding and not the other way around,” says Roberts. “After Yates, the training didn’t change—I mean, any person could try to do the Mentzer workouts he supposedly did, and they wouldn’t wind up looking like that—but the chemicals did. And so were all the guys who came after Yates. They were just so immense. Guys got on the bodybuilding stage at 270 and 280 pounds. It was exciting; it was a genuine advance.”

Roberts and Bell believe these periodizations are critical to understanding the evolution of the sport. The first generation of bodybuilders who competed in Mr. America during the 1940s and 1950s represented what competitors might hope to achieve through diet and exercise—echoes of their “classic” physiques can be seen in the bodies of promising young athletes who have yet to experiment with steroids, or who’ve used only small amounts. Then came the early Mr. Olympia winners—products of the Dianabol era, all somewhat bloated and smooth, a time when young Schwarzenegger himself was still slightly puffy. By the end of his Olympia streak, however, Schwarzenegger was lean and razor-sharp, closer to future winners Frank Zane and Chris Dickerson than he was as the younger and raw “Austrian Oak.” These men advanced bodybuilding into the 1980s, seemingly exhausting the sport’s chemical possibilities: They knew which steroids helped them gain mass and which steroids and other drugs helped them improve their definition. Dorian Yates—with a humongous physique built through the assistance of cheaper HGH—inaugurated a new age, a profound moment in the development of the body, after which fans have witnessed only minor cosmetic tweaks in the appearance of the competitors.

The latest cosmetic change, Roberts explained, is the result of targeted, sculpting-oil injections or implants similar to what people seeking more ample posteriors have sought from plastic surgeons. “Now they’re the cutting edge in bodybuilding, putting finishing touches on these bodies that are impressive but really quite dysfunctional, when you think about it. Maybe a strongman or athlete could look like a bodybuilder from the early 1960s, but there has never been any athlete—a functional performer in an athletic endeavor—who looked like most of today’s guys.”

But athletic prowess wasn’t what anyone ought to have been watching for at the 2016 Olympia. Instead, it was the fulfillment of the inevitable triumph of reigning champion Phil Heath, who looked as large as any other man on stage but who had the advantage of already being champion. For the better part of a decade, Heath had earned recognition as the man whose training regimen, genetic profile, performance-enhancing-drug use, and personality set him apart from his opponents. One studied Heath because he represented the current state of the art.

The bodybuilding pageant everyone expected Heath to win—the reason for the season, as it were—took place at the Orleans Hotel, an aging and somewhat nondescript casino about five miles from the Las Vegas Convention Center. The program spanned two nights, with the first night featuring all of the invited competitors performing their seven mandatory poses—Front Double Biceps, Rear Double Biceps, Front Lat Spread, Rear Lat Spread, Side Triceps, Side Chest, and Front Abdominal-Thigh.

Much of the online conversation on the forums of Bodybuilding.com, T-Nation, and elsewhere, revolved around these poses and the athletes who would hit them. Douglas Alexander, my cousin and an aspiring physique athlete, fed me all of the latest gossip on the competitors as I waited in the press pit for the first night to begin.

“They’re saying Big Ramy leaned out this year,” he texted me, referring to Egyptian competitor Mamdouh Elssbiay’s alleged decision to take the Olympia stage twenty pounds lighter than the previous year. “But I’m sure his quads are still amazing. Watch that thing he does with his quad,” he added, adverting to how “Big Ramy” swings his hypertrophied quadriceps muscle back and forth like a bowl filled with jelly.

Most of the first evening passed uneventfully, because bodybuilding itself is largely uneventful, characterized by repetitive posing performances that quickly blur together in the spectator’s mind. The most exciting part of the three-hour show was Women’s Fitness, a competition comprised of gymnastics and dance, which represented the only real display of athleticism—through handstands, flips, one-handed planks, and other such maneuvers—at the entire event. And yet few in the crowd really seemed to care; the gallery was still only two-thirds full, and people kept leaving to buy snacks and use the restrooms. Women’s Physique—a variant of bodybuilding that emphasizes feminine aesthetics, overall beauty, and muscle definition rather than size (which I erroneously assumed was a featured part of the Olympia)—had been held earlier in the day at a small stage in the rear of the convention center.

The marginal role of women on the competition stage was part of a longer and more puzzling trend. After circulating a memo in 2005 ordering female competitors to decrease their muscularity by 20 percent, the International Federation of Bodybuilding and Fitness (IFBB) discontinued women’s bodybuilding—the original Ms. Olympia competition, which predated the women’s physique and fitness competitions—in 2015. Once the subject of the second Pumping Iron documentary—a little-seen follow-up to the original released in the mid-1980s—women’s bodybuilding has been dying a slow death, due partly to the aesthetic concerns of IFBB officials and spectators alike. Female bodybuilders labored under a heavy burden: They were expected to appear muscular but not too muscular, even as they trained to compete in an event designed to showcase muscularity. And, unlike their male peers, many of whom viewed descriptions such as “muscle monster” and “freak” as badges of honor, women to whom fans might affix such labels faced the loss of lucrative sponsorships and other perks. In a sport ostensibly dedicated to pushing the outer boundaries of the human body, it was telling that women’s bodies remained constrained by official fiat, backed by the tacit approval of spectators.

“It’s still verboten for women to talk about their steroid use,” Roberts said. “Women who use steroids conjure up images of Chyna and Nicole Bass”—large female bodybuilders who participated in pro wrestling—“with those messed-up faces from prolonged hormone abuse. Even those women whose careers clearly depend on steroid usage, at least at very low levels, won’t discuss it. Right now, there’s no female bodybuilding star who is open about taking steroids; there’s no outspoken female steroid expert. Women who rely on steroids to sell the products they endorse have to pass themselves off as ‘fake naturals’ in a way that men don’t. And it’s weird, because more women are lifting weights and doing strength-building exercises than ever before. It’s a terrible double standard that benefits men. Women are forced to stay quiet or, even worse, lie about what they’re doing.”

The IFBB now offers extraordinarily traditional content in terms of gender roles, even as sports like CrossFit and mixed martial arts have profited from defying them. Once upon a time, the bulked-up figures of Cory Everson and Bev Francis loomed over women’s bodybuilding and the sport seemed to have a bright future. But even as the convention floor at the Olympia was now full of female fitness fanatics, female CrossFitters, female powerlifters, and female physique celebrities, the competition stage was all about the male mass.

The agents of mass who followed the women’s events did not disappoint. They were in fact so closely matched that only immutable characteristics, such as height and skin color, distinguished them. Kevin Levrone, a stellar performer in the 1990s, and now fifty-two, was among them, with a much-diminished upper body and, at least by the standards of the sport, subpar legs. “He got out because he was struggling to maintain the lower body,” Markus Rühl, a former Mr. Olympia competitor, told me as he cheered for the man he’d once competed against. “But I think he is in good form tonight.”

Levrone, the so-called “Maryland Muscle Machine,” got plenty of sympathy applause, in part because he lost a number of closely contested Olympias during the late 1990s and early 2000s. Levrone was only five years older than fellow competitor Dexter Jackson, another contemporary of both his and Rühl’s. Jackson, by comparison, was perfect from top to bottom—a fact his rowdy cheering section acknowledged repeatedly, screaming their support for him.

“Dad’s going to win,” Jackson’s daughter Myah said. “He looks unbelievable.”

The finals didn’t want for drama, but it was all minor drama, localized drama, low-stakes drama. Myah Jackson and her family continued to shout their support for Dexter Jackson, until they received a text from the eventual third-place finisher that Phil Heath had already begun celebrating, even before the last posedown among the finalists. (Heath had apparently received early word of his scores and placement from someone within the organization, though his victory hardly came as a surprise.) Rühl clapped heartily for Levrone’s bonus posing session; the old pro hadn’t been among the top ten men invited to pose on the second night, but he had been granted a special opportunity to appear before his fans. Levrone cried and shook as he struck and held each pose for the last time. But neither Levrone’s nostalgia appeal nor Dexter Jackson’s fabulous conditioning mattered in the end.

What mattered, as Anthony Roberts had repeatedly told me, were continuity and respect for the IFBB brand. Heath, who racked up his sixth consecutive Olympia, was at least as good as any bodybuilder currently in the sport. Moreover, with a background in Division I college basketball, Heath had a legitimate athletic pedigree. Even better, there were no skeletons in his closet. Bodybuilding was a seamy business, but the movers and shakers still preferred that their biggest stars have a certain maturity. Haney had a college degree and a background in youth counseling; Schwarzenegger had that million-dollar smile and business sense; and Ronnie Coleman was a beat cop in Texas.

Heath’s dominance became even more valuable to the IFBB when Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson, a former WWE champion and a box-office superstar, took the stage. A six-five powerhouse, Johnson dwarfed every bodybuilder up there with him, and had come to announce what was touted as the biggest news in modern bodybuilding history: His production company had just cut a deal with CBS Sports that would finally bring the Olympia back to network television. Given that bodybuilding has never made for compelling television—even WWE impresario Vince McMahon failed to create a weekly national bodybuilding show in the early 1990s—the idea that an upstart would be gunning for veteran champion Heath’s crown seemed like a vital story line. This was the model used in Pumping Iron, which was edited in such a way as to make it appear that Lou Ferrigno and Schwarzenegger were ferocious rivals. The more recent Generation Iron did the same thing with Heath and his eccentric opponent Kai Greene.

Johnson, who owes his spectacular midforties physique to the efforts of bodybuilding trainer George Farah, appeared to be overestimating the appeal of the sport in much the same way that his mentor McMahon did. McMahon, like Johnson, cuts a hulking figure and has relied on bodybuilding routines to maintain his impressive physique well past his athletic sell-by date. There is something about the sport that each man believes in, that appeals to them—but what? Perhaps the public’s appetite for this material has changed in the nearly thirty years since McMahon launched his World Bodybuilding Federation; perhaps the result will be different. Past performance doesn’t augur well for its future, but there is a chance that the sport could achieve a degree of mainstream appeal. Sports such as mixed martial arts and NASCAR took a long time to connect with viewers. Perhaps it’s reasonable to believe that bodybuilding’s time has come, too.

At any rate, the potential embrace of the sport by a larger audience would seem to forecast—implicitly, at least—an embrace of steroids. If knowledge of performance-enhancing drugs became more widespread, the way cannabis use in movies and television increased awareness and preceded decriminalization in some states and legalization in others, maybe this mass-market version of the Mr. Olympia could succeed. In that way, the private steroid culture of the competition would be disseminated more widely, perhaps to the point at which color commentary during these events would combine discussions of posing acumen with analysis of steroid cycles, of drug use, of an athlete’s choice of site-injection oil to mask his weakest areas.

“It’ll never happen,” Aaron Cook, an amateur powerlifter and close friend, said to me when I shared this idea with him. “Though, man, I’d love for it to happen, because honestly, I think when everyone is on steroids, it gets us back to genetics, only this time it’s whose genetics tolerate steroids the best, whose body reacts the best to steroids. I’ve been using for years, and while I’ve gotten results, I look like garbage. Yet Phil Heath looks amazing. I want to know what he takes, what he uses. That’s my dream, to watch experts talk about that on TV. But I don’t know that many other folks share that dream.”

“Past attempts to market bodybuilding to a mass audience have failed,” said Roberts. “They will probably continue to fail. Bodybuilding as a competitive sport is a niche activity. However, the community that surrounds it, the community linked together by bodybuilding praxis—drug use and training—is much larger and more consequential. I’m not sure how you capture that and sell it to the American public. Can you televise a festival like Burning Man, turn that into some media event? Most likely not. However, I think people who value this community, whether they’re McMahon or ‘The Rock,’ quite understandably think it might resonate with others. Even if they’re wrong, I think that speaks to the kind of community this is: People get involved in bodybuilding as a hobby and it becomes an entire mode of existence.”

As I waited for Chris Bell to give me a ride back to my hotel, I introduced myself to Flex Wheeler, a retired bodybuilder who had won the Arnold Classic four times.

I asked Wheeler, who remains widely regarded as the greatest bodybuilder of all time, about the return of Kevin Levrone.

“I don’t know,” he says. “I guess what Kevin did makes me want to get back in that kind of shape, but then part of me knows I can’t, because I wouldn’t be coming back at half of what I was. How I was back then is how I want my fans to remember me, you know?”

“What about the thrill of participating?”

“I look at my old pictures and feel a lot of joy,” Flex replied. “I looked great in them. I was just right on point. Participating wasn’t about the process, you know, it was about getting to those moments—and I nailed it. I really nailed it.”

Six months later, Wheeler announced his plans to compete in the 2017 Mr. Olympia. He had set aside his earlier concerns about presenting fans with a diminished body; he wanted back in because this was where he belonged. He was returning to the fold.