The road to Cal State Fullerton baseball greatness is littered with parking tickets

Cal State Fullerton has been so good at baseball for so long that it’s easy to forget just how fragile success can be at a commuter school off the Orange Freeway.

Like how the program almost got taken down by parking tickets.

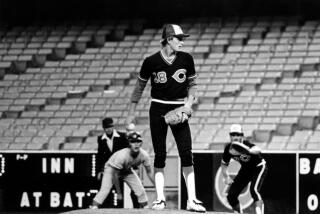

It took former coach Augie Garrido a few years, but he got fed up with battling for a spot in the faculty lot, a 10-minute walk to the baseball field. So he began driving his car onto the field and parking it there.

“I guess a month went by and I got a phone call, and it was the head of the campus police,” recalled Neale Stoner, the athletic director at the time. “And he said, ‘Mr. Stoner, are you aware that Coach Garrido is parking illegally in the baseball complex, and he’s getting a ticket a day?’”

Stoner promised to set Garrido straight.

The next call Stoner received was from the school’s president, two weeks later. But Garrido still wasn’t budging.

Months passed. Thirty tickets became 100 … 200 … 300 ... until a couple of sheriff’s deputies showed up at Garrido’s Christmas party, handcuffed him and took him to jail.

Thirty days later, the coach faced a judge.

“The judge must’ve recognized me,” Stoner said. “Because the judge had started admonishing me and Dr. Shields, the president, for not providing a better parking spot for this outstanding faculty member.”

The final tally of tickets was north of 400. The judge’s sentence: a fine of $25.

“What was funny about the story,” Stoner said, “where do you think he parked the next day?”

The story illustrates just how difficult was it to grow Fullerton baseball into what it is today — when it took one of the game’s best coaches 18 months just to upgrade his parking spot.

Twenty-one years after Garrido last coached at Fullerton, the school remains a one-sport wonder, like Gonzaga in men’s basketball and Johns Hopkins in lacrosse. It has produced four national championships, three players who have won the Golden Spikes Award and one of the best college baseball teams in history, the 1995 national title winner.

The Titans have never had a losing season in Division I. Even with a relatively modest record of 34-21 this season, Fullerton qualified for its 26th consecutive appearance in an NCAA regional. The Titans are the No. 2-seeded team in the Stanford regional and will open against Brigham Young on Thursday.

“Baseball,” said Steve DiTolla, an associate athletics director, “is our brand.”

Fullerton’s last national championship in any other sport was in 1989, in men’s bowling.

Why has Fullerton baseball flourished? “Two words,” Stoner said: “Augie. Garrido.”

But striking gold with a coach is only part of the recipe. Judi Garman, an elite softball coach, led the Titans to a Women’s College World Series title in 1986. But that kind of success didn’t last.

One reason Fullerton has stayed on top is that the school makes baseball a priority. The Titans haven’t had a football program since 1992.

“Within the Fullerton department there were probably a lot of envious and jealous people,” said George Horton, who guided Fullerton to a national championship in 2004 and is now the coach at Oregon. “We were getting more than most.”

Of course, it wasn’t always that way. The baseball program took some early concrete action that helped it grow into a behemoth.

Humble beginnings

In theory, there was a baseball budget when Garrido took the job in 1973. But it didn’t pay for facilities: The players changed clothes in the parking lots.

It did not pay for food or travel, either. The players packed their own lunches and drove themselves to away games. Nor was there money for assistant coaches. Dave Snow’s first year on Garrido’s staff netted him a $90 loss — he had to pay for graduate school tuition.

“It was more or less a club sport playing in Division II,” Garrido said.

One student recalled walking past the baseball field each day on the way to his fraternity house. It looked like a high-school field, he said. Still, he was intrigued by the program and said he would have become a regular fan — had there been such a thing. “There weren’t any,” said the student, Kevin Costner, who became an actor and director and is one of the program’s longstanding supporters.

Amid the dereliction, Garrido and his assistants identified two areas where they could compete, each complementing the other. First, they would establish better recruiting networks in the fertile Orange County area. Next, they would turn those recruits into baseball Ph.D.s

At the time, Garrido said, most college baseball coaches operated like major league managers. They assembled talent from local high schools, but instruction wasn’t a priority.

“We had to create a better player-development program than the minor leagues provided,” Garrido said. “That was our goal.”

To start, Garrido raided the under-recruited junior college ranks, turning Cerritos College effectively into a feeder program. Garrido, it turned out, had a gift for spotting overlooked talent.

“Augie was a guy who would’ve recognized ‘Dances with Wolves,’” said Costner, who won the Academy Award for best picture and best director for the film.

Back then, there were no limits on practice time, so Garrido’s teams played constantly. Before the 1979 season, he scheduled 55 games in the fall. Then the Titans played another 74 in the spring and summer, and had practice just about every day between.

Dave Weatherman, a pitcher on the 1979 team, said freshmen pitchers were given a sequence to throw in practice. The catch: The batters knew the sequence.

“To me, that seemed extremely unfair,” Weatherman said.

At first, he got shelled. But over time, a lesson kicked in. “You start realizing that if I hit my spots, even if these guys know what’s coming, I’m going to be successful,” Weatherman said. “So now your focus is not Tim Wallach, your focus is on low and away. It changes what you think about out there.”

Buoyed by Wallach, who enjoyed a 17-year major league career in which he was a five-time All Star, Fullerton made it to the 1979 College World Series. Weatherman pitched in the national semifinal but lasted a third of an inning. As he sulked, Fullerton came back to win.

After, Garrido swaggered into the locker room and told Weatherman he was pitching the very next day in the championship game.

This time, Weatherman allowed just one run, and Fullerton won its first title.

Turned out, Weatherman said, it helped to forget about the moment and the batter and just hit his spot.

Leadership investment

In the early years, even after that national championship, football was still siphoning away a significant portion of what Fullerton had to spend on athletics.

That left Garrido fighting for scraps. “The absolute basic necessities to be able to play ball,” he said.

Stoner worried that a richer program would poach Garrido, and finally one did. When Stoner left to become Illinois’ athletic director, he took Garrido with him.

Garrido coached Illinois for three years before Fullerton hired him back, a turning point for the Titans. The relationships Garrido had built banded together to subsidize his contract.

“That was very unusual for Cal State Fullerton,” said DiTolla, who was the athletic director when Garrido was rehired. “At that time, we didn’t really have a staff to actually man a fundraising department.”

The school also enticed Garrido back by making good on a long-promised upgrade: A new baseball stadium.

Garrido stayed six more seasons and won his third national championship before leaving for Texas. But now the program was in a better spot. It had real facilities. It had a stable network it could tap for income. And it had a replacement personally groomed by Garrido.

New edge to an old formula

It was 2004, eight years after George Horton had taken over as coach for Garrido, and it had been a weird season. The Titans, after limping to a 15-16 start, now needed just one win in their final series against Long Beach State to clinch the Big West Conference title.

Problem was, Long Beach’s ace was Jered Weaver. And Weaver was nearly unhittable. To assure at least one win, Horton wanted to mismatch his rotation — throw his own ace, Jason Windsor, later in the series so that he wasn’t matched against Weaver.

Horton revealed the plan to his team.

“They looked at me like I told my daughters everyone else could be out until 2 on prom night, but you have to be in at 10,” Horton said. “We finally decided, hey, we’re Cal State Fullerton, we don’t mismatch anybody.”

Horton, like Garrido before him, recognized the importance of having players with confidence. And there was a reason for that: Horton had been groomed by Garrido.

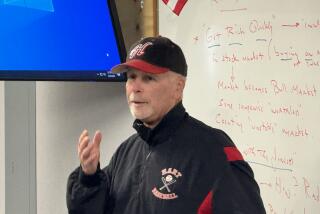

Even wealthy programs can wither after the departure of a legendary coach. “We all see it in other sports,” said Rick Vanderhook, Fullerton’s current coach. “Who took over for John Wooden, Gene Bartow? No-win situation.”

But with continuity, a program can survive losing a top coach. And Fullerton has.

Horton, Vanderhook said, was the only person who could have replaced Garrido. Horton played for Garrido, then coached under him. During Garrido’s final years with Fullerton, Horton assumed some of the head coach’s responsibilities. When Garrido left, Horton said, there wasn’t much of a transition.

All three Fullerton coaches since Garrido’s departure either played or coached under Garrido. The style of play, more fundamentally solid than overwhelmingly powerful, remained the same.

Horton’s decision against Long Beach State paid off. Weaver blanked Fullerton through eight innings. But the Titans used a two-out rally to tie the score and won in extra innings, 2-1. They then swept the series and stormed through the NCAA tournament to win the national championship.

The runner-up: Texas, coached by Garrido.

The championship was difficult to fathom. Garrido was considered the best coach in college baseball, and his program at Texas had far more resources than Fullerton.

Yet somehow the Titans had found a new edge. Or, actually, one found them.

In 1991, the NCAA limited the maximum number of scholarships for a baseball team to 11.7. Consequently, even the best players typically get only partial scholarships. Vanderhook said in his 27 years as a Fullerton assistant and head coach, the team has offered only one player a full scholarship — to Alex Rodriguez, who passed. .

At many schools, Vanderhook said, that means “you have a choice: Your mom and dad better make a lot of money. Or you’re going to have to take out a lot of student debt.”

Advantage Fullerton. And it’s a powerful advantage.

For example, the full cost of attending USC next year is $72,273. At Fullerton, it’s $27,106. So half of a scholarship to Fullerton leaves about a $13,500 debt — a little more than a third of what it would be at USC each year.

The difference allows Fullerton’s baseball program to recruit more depth. It’s an advantage blunted in women’s sports, which generally have higher scholarship maximums per team.

Baseball’s budget still cannot compete with Atlantic Coast Conference or Southeastern Conference schools, but deals with Nike and Easton help supplement the incomes of Fullerton coaches, DiTolla said. Those contracts are possible because the Titans have a track record that all but guarantees exposure in the NCAA tournament.

Fullerton games today resemble Fullerton games when Garrido was in charge. Vanderhook still stresses player development, and his players still have a reputation for being fundamentally sound. They don’t see the field until they’ve mastered even relatively rare situational strategies.

“Maybe once, twice, three times in a year it really matters,” said Taylor Bryant, an infielder. “But when it matters, it matters.”

But if it sounds like the program hasn’t changed much from Garrido’s first few years, that’s a bit misleading.

Stoner, now retired, goes to games every so often. At a game a few years ago, he noticed two parking spots blocked off. One was for the famous Costner. The other was for Garrido, who lives in the area in retirement.

It was about 10 feet from the entrance.

Follow Zach Helfand on Twitter @zhelfand

More to Read

Get our high school sports newsletter

Prep Rally is devoted to the SoCal high school sports experience, bringing you scores, stories and a behind-the-scenes look at what makes prep sports so popular.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.