In 1921, the Football Association ruled the sport “quite unsuitable for females and … not to be encouraged”. For the next 50 years, women were banned from playing on FA pitches. A new theatre show, Offside, brings this hidden history to light. “So many people were unaware that there had been a ban,” says the show’s co-writer Sabrina Mahfouz, “even people who are playing football now”.

The play emerged from Caroline Bryant’s passion and frustration. A lifelong football fan, she was never able to play for a team when she was growing up. Decades later, as artistic director of the company Futures Theatre, which is committed to promoting equality for women, it seemed to her an injustice that was ripe for dramatisation. “Football is so much a part of British and world culture,” says Bryant. “Why are women excluded from it?”

Poet Hollie McNish, who wrote the play with Mahfouz, describes the women’s game as an “amazing little microcosm of the history of women’s rights”. Over the years, it’s been caught up with the fight for equality in a variety of areas. The rational dress movement of the late 19th century was partly driven by women fighting to wear clothes that were suitable for playing sport, while women’s football in Scotland was closely linked to the campaign for female suffrage. These were the stories that Mahfouz and McNish sought out.

Based on current and historical research, the show intertwines three narratives: one contemporary, two historical. In the present, fictional characters Mickey and Keeley are pursuing their dream of playing for England. Spurring them on from the history books are Carrie Boustead, a black female footballer who was playing in the 1880s and 90s, and the National Football Museum hall of fame star Lily Parr.

As Mahfouz explains, Boustead and Parr’s stories “act as heroic, retrospective examples that the two contemporary football players use to motivate themselves”. These interwoven stories are performed by a cast of three against the backdrop of a handmade patchwork that includes various nods to the game’s history, from suffragette protest banners to more recent feminist iconography.

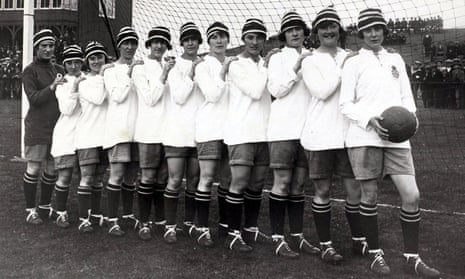

The little-known story of Boustead, who played as a goalkeeper, counters what Mahfouz calls the “whitewashing” of British history. Parr, meanwhile, was a winger for Dick, Kerr Ladies, the team that on Boxing Day 1920 drew a crowd of 53,000 to Goodison Park. Dick, Kerr Ladies and other teams of female factory workers had steadily gained popularity during and after the first world war, but in 1921 the FA banned the women’s game from its grounds, citing medical concerns over its effects on women’s health. The ban crippled the burgeoning sport, forcing Parr and her peers to play on village greens.

The ban persisted until 1971, two years after the formation of the Women’s Football Association, when the FA bowed to pressure from Uefa to once again allow women to play on its grounds. Today, 46 years on from the lifting of the ban, the women’s game is stronger than ever, but the gap between women’s and men’s football remains.

“There was just such palpable frustration,” says Mahfouz, reflecting on her conversations with players. Leanne Cowan, Millwall Lionesses defender and one of the women interviewed for Offside, tells me that she works three or four jobs alongside training and matches in order to do what she loves. Such a situation is not uncommon for female footballers, while their male counterparts earn often astronomical sums.

“It was astounding, really, that this love of this game could keep them going,” says Mahfouz. McNish, despite being a football lover, was amazed that female players of the past loved the sport so much that they fought “for the right to kick a ball”.

Bryant believes that “we are at the cusp of changing all this now”. A key turning point was the 2014 match against Germany at Wembley, which attracted 55,000 spectators. Meanwhile, more clubs are paying their female players on a full-time basis and attitudes are beginning to change. As Cowan says: “The game is getting bigger every year.”

“I think it’s important to recognise that things have been created this way and it’s not just how it is,” says Mahfouz. Bryant, too, insists that it’s vital to remind people of the setbacks that female footballers have faced. “When people say the game’s not as fast or as entertaining as the men’s game, I want them to know that for 50 years women weren’t allowed to play.”

The hope is that Offside will shift attitudes. “I want the audience to be a bit pissed off at the way female sportspeople are still portrayed,” says McNish. For Bryant, the ultimate aim is to reach the point where the men’s and women’s games are on a level in people’s minds. “The greatest thing for me will be when they interview a manager at the end of the game, it’s a woman, and no one says anything about it – it’s just normal.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion