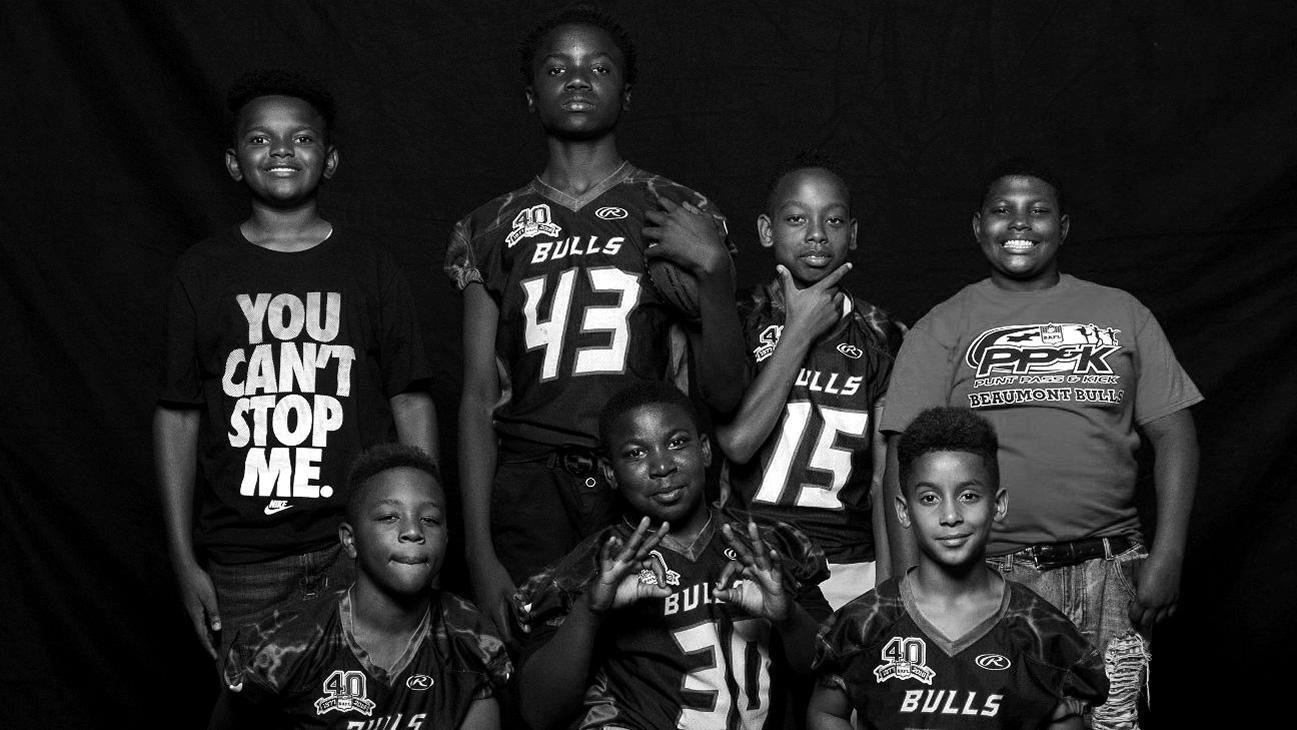

Oh, say can you see, by the dawn’s early light, What so proudly we hailed at the twilight's last gleaming? Whose broad stripes and bright stars through the perilous fight, O'er the ramparts we watched, were so gallantly streaming, And the rockets' red glare, the bombs bursting in air, Gave proof through the night that our flag was still there; Oh, say does that star-spangled banner yet wave O'er the land of the free, and the home of the brave?

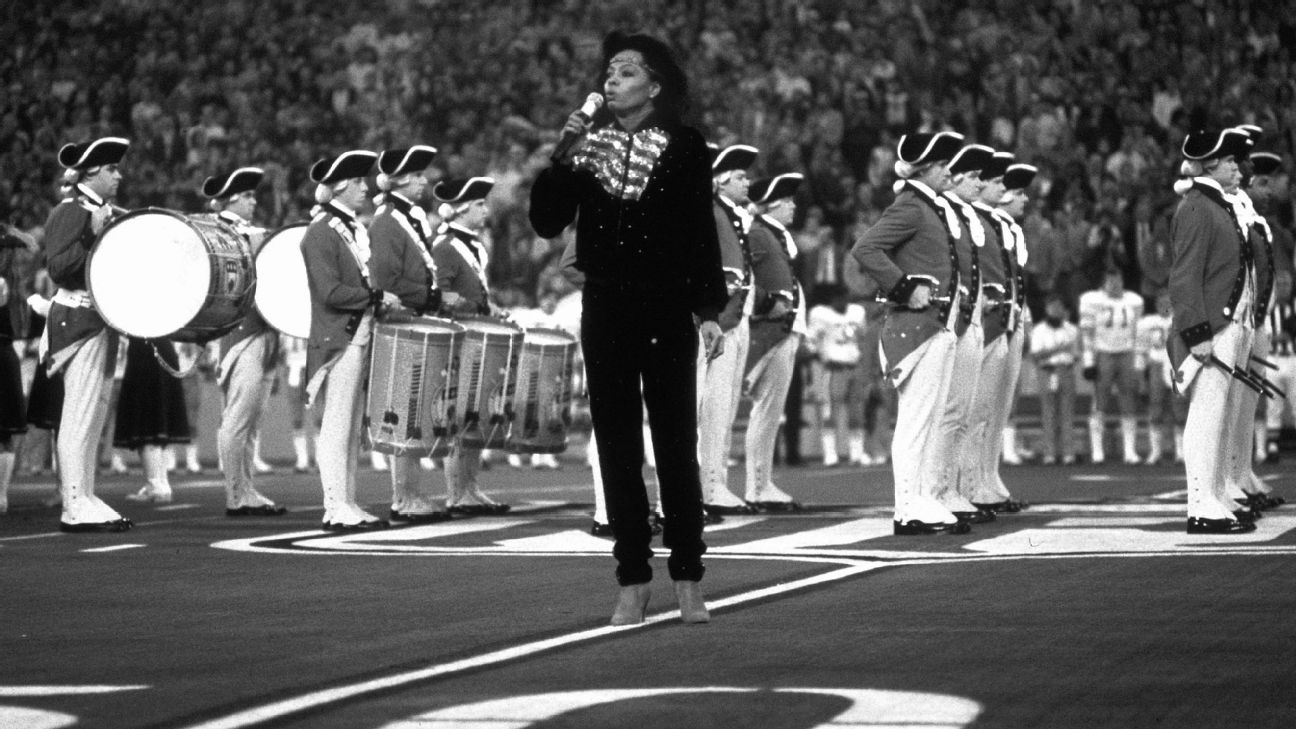

Ezra Shaw/Getty Images She did not have to think very hard or for very long about how she was going to sing the song before she opened her mouth to sing it. She had been singing it all her life, in every possible setting and situation. She sang it at the opening of the Democratic National Convention in the riven year of 1968; she sang it with Aaron Neville and Dr. John at the 2006 Super Bowl; she sang it at Harvard’s commencement in 2014. Now, singing “The Star-Spangled Banner” on Thanksgiving Day, 2016, Aretha Franklin would do what she always did and make the song her own. She would let everybody else think about it. “I thought I’d do what people ask for,” she says, with an imperial emphasis on the words and syllables of her choosing, a queenly habit of speech. “They want to hear me play the piano, so I played the piano. I think that they were surprised by the length of it -- but that they absolutely enjoyed it.” She had chosen the simplest of accompaniments: herself, on piano; a distinguished-looking man with a gray beard adding occasional fills on an organ, as in a church. But Aretha Franklin took her time. Lingering over every chord and elaborating on every phrase, she took nearly five minutes to sing a song she usually delivers in three, prompting a national audience to ask not what she was singing but what she was saying. She made “The Star-Spangled Banner” into something like a spiritual. Was it a gesture of thanksgiving or of defiance? Was it a prayer or a protest? 2016 had been a year like no other -- a year in which anybody singing the national anthem before a sporting event faced the very real possibility that the athletes gathered in the arena would decide to sit it out. Lions and Vikings players all stood for Aretha on Thanksgiving Day. But did she make the song her own in order to make the song their own? It was the national anthem, after all. It was supposed to belong to everyone. But when a singer makes it her own, whom does it belong to? SING IT. Go ahead, it’s not that hard. Sure, it’s supposed to be a challenge -- by now it’s American opera. But we the people have been singing it for a lot longer than we’ve been merely listening to it, certainly for a lot longer than we’ve made it the province of divas. It’s a couple of ticks past two centuries old, and for most of its existence we had to sing it if we wanted to hear it. And so we did; we sang it in all sorts of ways, even with all sorts of words. It wasn’t holy writ, at least not at the beginning. It was just words a man wrote down on a folded-up piece of parchment paper to a tune in his head. The tune was already familiar, if not shopworn. It belonged to the people who sang it in taverns and music clubs, their tongues loosened by a little liquid courage. Nine years earlier, he’d used the tune for another song, a sentimental ditty about a warrior’s return. But now he’d seen something; he’d witnessed something and he felt the need to write down what he saw. He wrote down the first verse in the morning -- yes, by the dawn’s early light -- on the British ship where he, as a gentleman, had been fed and politely detained. He wrote the rest in a hotel room in Baltimore. It was news, duly printed in the local newspapers almost as soon as it was composed, but more than that, it was meant to be sung, and so the news that Francis Scott Key reported in a triple rhyme has managed to stay news for as long as Americans have managed to sing it: Our flag was still there. It is hard to remember -- hard even to imagine -- a time when the singing of “The Star-Spangled Banner” as prelude to the Super Bowl was anything less than a test of the singer’s chops, patriotism, sincerity and resolve, proctored by something like half a billion of the world’s eyes and ears. It is the part of the pageant that must rise above pageantry; the exclamation point delivered before the start of the sentence; the national gut check that signals, for many, the end of dinner and the start of the game; and, not incidentally, the biggest musical event of the year, at least in terms of the global audience it commands. No sooner do we learn who has been selected to sing than we begin wondering whether he or she is up to it, has the range, possesses the stature, represents both our nation and our time, and, most important, can hit the notes. It’s the first cliff-hanger of the game, and the issue is not decided until the singer scales the heights demanded by the land of the free-eeeeeee ... and then manages to harmonize with the fighter jets summoned to split the skies overhead. But it was not always a show of force. For the first, um, XV years of the Super Bowl, the performance of the national anthem was mostly something of a community effort, left to marching bands and local choirs, a beauty pageant winner and the kind of jazz trumpet players who are beloved by squares. The national anthem wasn’t played at Super Bowl XI, and even after the NFL hired Jim Steeg to fashion the Super Bowl into a spectacle commensurate with the nation’s-- and the league’s -- sense of exceptionalism, the bookings could be casually arranged. Why did Cheryl Ladd, the replacement Charlie’s Angel, sing the anthem for Super Bowl XIV? “Pete Rozelle ran into her at the Polo Lounge of the Beverly Hills Hotel -- that’s how she was booked,” Steeg says. Why did grandmotherly Helen O’Connell warble the anthem a year later? Rozelle’s second-in-command “was in love with Helen O’Connell from the big-band era in the ‘40s.” It was Steeg’s idea to hire a pop star for Super Bowl XVI. “The game was in Detroit, and I told Pete, ’There’s only one person who can sing the national anthem in Detroit.’ He said, ’Go ahead, kid -- go do it.’ So we got Diana Ross, and she represented a change in everything we were doing. All of a sudden, you had star power.” “I think that they were surprised by the length of it -- but that they absolutely enjoyed it.” Aretha Franklin in 2016 Ross sang it a cappella in front of 81,000 people at the Silverdome. She never had a big voice, and as the first icon who had to figure out how to strike a balance with all that iconography, she was the last Super Bowl performer to ask the crowd for help-- to say “Sing with me!” And they did; the players did, the coaches did, the fans in the nosebleed seats did, and their gathered voices, when you listen to them today on YouTube, sound not just like a rough chorus accompanying Diana Ross but like the echo of another age. Francis Scott Key was not alone when he saw -- when he wrote -- that our flag was still there. He was in the company of the enemy, detained while it bombarded Fort McHenry, which stood athwart the harbor in Baltimore. The fort’s defenders were being shelled from a distance that their own guns could not match, so all they could do was endure the attack by sea while the British dispatched a force to attack Baltimore itself by land. Thirty-one years earlier, the United States of America had disengaged itself from Great Britain by means of armed revolt, but now it was a young and very weak nation at war with an old and very powerful one, and the outcome was very much in doubt. A few weeks before, the British had entered Washington, D.C., and put many of its public buildings to the torch, including the Capitol and the White House. “We could very easily have been British again,” says Jennifer Jones, who curated the Smithsonian’s 2014 exhibition celebrating the bicentennial of “The Star-Spangled Banner.” “The Americans were this nagging problem that the British were trying to put down.” What Key beheld on the morning of Sept. 14, 1814, was not just unexpected; it was, says Jones, the martial equivalent of a Hail Mary pass that won the game as time ran out. And the line that provides the central affirmation of the song he wound up writing is not just a declaration; it’s the answer to an implicit question that animates the song’s every verse and stanza. Was the flag still there? It was. British ships did not get by Fort McHenry; British troops did not enter Baltimore; the War of 1812-sometimes called our Second War of Independence -- confirmed America’s global standing and foreshadowed the rise of American power. Key had gotten an inkling of that power; indeed, he’d had a vision of its nature, which was to be continually under siege. It was a new kind of power, an almost oxymoronic kind of power, at once democratic and expansive, and so, to celebrate it, he married his vision to a song notorious, even then, for being hard to sing. The song was “To Anacreon in Heaven,” and it was composed for the members of an all-male British music society, who often sang its fusty lyrics while drinking. “That’s why it’s hard,” says Mark Clague, a University of Michigan musicologist whose website, StarSpangledMusic.org, is the fruit of half a lifetime spent studying and performing the national anthem. “It’s meant for a trained voice, an operatic voice -- it’s a show-off song, which is why Key chose it. He was saying, ’Hey -- we just beat the British.’ But you have to have range to sing it, and it’s always been a scary song to sing.” There are five texts central to the American experiment: the Declaration of Independence, the United States Constitution, the Emancipation Proclamation, the Gettysburg Address and “The Star-Spangled Banner.” The first two are about invention; the last three are about reinvention amid the challenge and cataclysm of war. But only one has been set to music; only one was written to be sung and then left to the uncertain and invigorating mercy of a nation of untrained voices. She did not look scared when she took the stage to sing the song. She looked casual, dressed in a white tracksuit, with her hair kept from her face by a white headband. She looked less like a trained singer than like a trained athlete, and that’s how she sang the song -- like an athlete, living up to her moment. Of course, the moment was everything. When Whitney Houston sang the anthem for Super Bowl XXV in 1991, she was 27 years old, and the nation was at war in the Persian Gulf. Two years earlier, the Berlin Wall had fallen and America had emerged as the world’s only superpower; now we were in the process of making short work of Iraq, as if to prove our historical claim. It was a rare match: a country and a singer, both at the height of their powers and both heartbreakingly unaware that they’d ever be anything but. Steeg knew what he was seeing and hearing as soon as she opened her mouth. “All you had to do was look around,” he says. It was a display of freedom -- force coupled with apparent ease, as if she were insisting on the most fragile claim of American exceptionalism, which is that the most powerful country in the world could remain perpetually innocent. “Her performance elevated the whole thing yet again,” Steeg says. “The Star-Spangled Banner” had changed the NFL by connecting it to patriotic pomp. But now the NFL had changed “The Star-Spangled Banner” by giving Whitney Houston a platform to assert that anyone singing it in her wake would be singing it for the highest possible stakes. In a 4-minute, 32-second rendition on Thanksgiving, Aretha Franklin sang the national anthem “as I felt it.” AP Photo/Rick Osentoski In Constitutional Law, there is a philosophy called originalism, which insists that the only way to interpret the Constitution is as written, and the only intentions that matter are the intentions of the men who wrote it. But there is no one way to sing “The Star-Spangled Banner.” Between 1814 and 1900, there were at least 70 different versions, says Clague, “with people writing new lyrics about woman’s suffrage, about the peace after the Civil War, about the end of slavery.” It is a musical argument against originalism. It is America’s living document, and the law that made it our national anthem in 1931 said nothing at all about how it was to be sung or played. This is not to say that you can sing or play it any way you want to. The United States is not a country with a state religion, but it has a state song, and somewhere along the line -- maybe, as Clague says, at the moment when the U.S. fulfilled Francis Scott Key’s prophecy that it would become a great and powerful nation -- the song became sacred. The rituals around it became sacred, and compulsory. You might not have to sing, but you damn well have to stand, and you better take off your hat ... and if you do sing, you have to sing with humility, sincerity and respect, and without a hint of irony. It is the great tug-of-war at the heart of the song, the great tussle. As the Smithsonian’s Jennifer Jones says, “Musicians are free to make the song their own. Americans don’t like that.” Of course, if you sing it as a member of an American minority, it is almost a different song altogether -- you have to make it your own in order to claim it as your own, with some of the most memorable versions of the national anthem turning out to be the ones that were performed under conditions of siege. In 1968, José Feliciano, the blind singer born in Puerto Rico, sang “The Star-Spangled Banner” as kind of a gentle folk song before a World Series game between the Cardinals and Tigers, accompanying himself on guitar. He thought it was going to be a hit; instead, thousands of Americans responded with howls of derision, questioning not only his performance of the song but his very right to perform it. A year later, Jimi Hendrix stood before the tribes at Woodstock and made a song inspired by the War of 1812 the soundtrack to the war in Vietnam. A few years earlier, he had gone to England as an R & B guitar player; he had come back to the States as the embodiment of both psychedelia and revolution and had been playing “The Star-Spangled Banner” ever since. He would wind up performing it 70 times. He was the closing act at Woodstock. He took the stage in the morning, and by the dawn’s early light, he seemed to almost literally invoke the bombs bursting in air. He used his guitar to evoke a state of emergency, emulating air-raid sirens and also a state of mourning, playing a few bars of taps. His “Star-Spangled Banner” was a warning, a prophecy, a threnody, an ecstatic dirge and, in the end, something akin to a public sacrifice. Hendrix did more than take liberties with a song dedicated to the cause of liberty; he gave birth to a tradition of the American anthem enacting the central drama of America itself, turning it into a song that dared singers and musicians to claim it for their own traditions, or no tradition at all. There was, before the 1983 NBA All-Star Game, Marvin Gaye’s agonized slow jam, which turned out to be one of his last public utterances before his father shot him to death after an argument; there was, of course, Aretha; and, a full quarter-century ago now, there was Whitney, whose Gulf War performance is usually considered the capstone of anthemic orthodoxy but who dispensed with the song’s stately European time signature -- it’s a waltz -- and sang it with a bounce, four beats to the bar. The song that declared Francis Scott Key’s surprise that the flag was still there has become a song of surprises, with not all of them gift-wrapped. Sebastien De La Cruz was surprised at the reception his respectful rendition of the anthem received. As an 11-year-old mariachi singer from San Antonio, he was pressed into service to sing the anthem before the Spurs played the Heat in Game 3 of the 2013 NBA Finals. He sang in full costume, with a soaring prepubescent enthusiasm, and was shocked, the next morning, when he did an interview with a local radio station and all the questions were about the storm of racist comments his performance provoked on Twitter and Facebook. The experience changed him; it also changed his relationship with “The Star-Spangled Banner,” so when he sang it last summer at the Democratic National Convention, he was not just a boy tenor who had grown into an adolescent baritone; he was, he says, a singer who sang the song for different people and for different reasons. “When I sang at the Spurs game, I was trying to represent San Antonio to the world-to show what mariachi and Mexican-American culture was really about. At the DNC, I wanted to show that I stand for something -- that I stand up for my roots but also everyone else’s roots, that I stand up for everyone who has problems in their life, especially about race.” Diana Ross asked members of the audience to sing along with her. AP Photo/Al Messerschmidt The first question? The first question is simple, Mark Quenzel says: Who can sing it? “It’s a difficult song, and it all comes down to who can sing it. Even some of the biggest stars in the world can’t sing the national anthem.” Quenzel is the presiding impresario of NFL Network, the arm of the NFL that produces the annual Super Bowl extravaganza. For the past six years, he has made his living selecting Super Bowl singers, a process he starts in the summer with an iron law: “There are no hunches when it comes to the national anthem at the Super Bowl.” The singers who sing “The Star-Spangled Banner” on the first Sunday in February have to prove that they can sing it, either by having sung it or by being unquestioned prodigies of range and control. But of course there are other considerations. “We look at it in terms of the overall image,” Quenzel says. “We look at what our place in the world is, because as big as the Super Bowl is, we’re part of a greater society. You’re never bigger than the national anthem. So we try to respect it, we try to honor it -- the big word around here is unity. The singing of the national anthem is by definition a unifying event.” He is not unaware of the timing. He is not unaware that since Colin Kaepernick first employed the national anthem as an instrument of protest in the summer of 2016, at least 42 players from 17 NFL teams have joined him with protests of their own. He is not unaware that there have been at least 134 protests at professional, college and high school sporting events. “Of course we take that into account,” Quenzel says. “But we look at it as an opportunity. It doesn’t change our basic premise that this should be a unifying moment, that this should be a time when people feel they have more in common than they have keeping them apart. We are focusing on the national anthem to make sure people feel included, that they feel that way about the anthem and about their country.” For the national anthem at Super Bowl LI, the NFL wound up picking someone who, in Quenzel’s words, “is a little more traditional” and “checks all the boxes we’ve been talking about” -- someone who faces the daunting task not only of singing the anthem but of singing it as an exercise in national solidarity. But can anyone possibly live up to such daunting criteria? Can anyone sing for everyone, and will any player sit, kneel or raise a fist as the anthem is sung? And if you don’t like what you hear or what you see during the performance of the national anthem, is there anything you can do? Well, as it so happens, yes --you can revert to originalism and do what Francis Scott Key meant for you to do: Sing it yourself. It’s not that hard. Yes, the song is something of a turkey, but it’s like the turkey compulsory for Thanksgiving, resistant of perfection but worth the fumbling effort. Something happens when you sing “The Star-Spangled Banner” not unlike what happens when you sing “Amazing Grace,” because the victory it celebrates is likewise so fragile and fleeting. Our flag was still there: It is one of the central affirmations of American life. But it is also the answer to a question, and the question is consecrated in the impossibility of the song. So go ahead and sing: It might be opera, but you know the words. And the words know you. When Aretha Franklin sang “The Star-Spangled Banner” this past Thanksgiving, she sang it 16 days after an election that divided the country. She sang it when the atmosphere of suspense built into the song -- how will she sing it? -- was extended to the audience: How will we hear it? And so she made the Lions’ domed stadium, Ford Field, into her own church, and she sang it as a kind of spiritual -- “It was not done as a spiritual,” she says, with a brisk snap of correction. “It was the national anthem as I felt it. That was my interpretation of the basic melody. The election had nothing to do with my performance. Nothing whatsoever. There is a basic melody that is tradition. And you have to respect the tradition. I added something at the end that had not been there. But I played the basic melody.” But the churchy sound of the chords she played on the piano and the time it took for her to play them, surely she -- “I did not do it as a spiritual,” the Queen of Soul says, with extreme finality. “I did it as the national anthem.” Amen. Chris Walter/Getty Images I had set out to sing an anthem of gratitude to a country that had given me a chance. That had allowed me, a blind kid from Puerto Rico -- a kid with a dream -- to reach far above my own limitations. I wanted to sing an anthem of praise to a country that had given my family and me a better life than we had had before. -- José Feliciano California’s official state song -- its anthem -- is a bit of 1913 boosterism called “I Love You, California.” The lyrics were written by a Los Angeles couturier and the original sheet music features a now-extinct California grizzly bear embracing the slim state like a lover. Used in a recent Jeep commercial, the song’s waxy charm melts in the rays of the Golden State’s unofficial anthem, “California, Here I Come.” Co-written and recorded in 1924 by singer and blackface performer Al Jolson, California, “Here I Come” was performed to its full-out extent by the Ricardos and the Mertzes in a 1955 I Love Lucy episode of the same name. The foursome is on New York’s George Washington Bridge, almost 3,000 miles from the Golden Gate Bridge, belting Open up / That Golden Gate! Mood: the American West is amazing, we want in, because all things are possible there. Cuban Desi Arnaz provides vaudevillian flourishes, Lucille Ball sings as if no one is listening, and they all look, as humans and as characters, like they are living their best lives. A few years later, Ray Charles covered “California Here I Come” for a 1960 concept album called The Genius Hits the Road -- it features his indelible “Georgia on My Mind:” Whoa / Georgia / Georgia / No peace / No peace I find. Charles sings the Hoagy Carmichael composition with the kind of hate and hope that one might harbor for a home state that happily enslaved one’s recent ancestors. Charles’ “California” on the other hand -- A sun-kissed miss said, ‘Don’t be late’ / That’s why I can hardly wait -- unfurls with the swag and quandary of new freedoms. There is of course the Beach Boys’ 1965 “California Girls” and Tupac Shakur and Dr. Dre’s 1996 “California Love.” Both hit singles surge with similar kinds of regional we-the-best-ness, however ironic or rebellious. When Shakur raps, Let me serenade the streets of L.A. / From Oakland to Sac Town / The Bay Area / And back down, if you are from California, and you love hip-hop, you can come dangerously close to saluting. And the beginning of his epic verse about liberty, and returning home? Out on bail / Fresh out of jail / California dreamin’. That’s the secret of these home songs, these pledges of allegiance, these rah-rah warnings. Everybody has one. Or 10. I mean, we haven’t even mentioned “Hotel California.” California has an actual anthem -- the song about it that has mattered most since the rock era -- and it’s the immortal “California Dreamin’.” The most compelling versions of the song (and there are many) are from Hugh Masekela, The Beach Boys, Bobby Womack, the Four Tops, and a 2015 cover from Sia, for the soundtrack of Dwayne Johnson’s San Andreas. The most famous and beloved recording of “California Dreamin’” is the gorgeously folk 1966 single from The Mamas and the Papas. There’s deep comfort in the call-and-response, and in the fever dream, when lost, of familiarity. There’s also frank selfishness -- If I didn’t tell her / I could leave today. And the foursome’s seamless harmonies shimmer with what can in retrospect seem to be the victory of being counter to a culture from within. There is a bold and erudite 1968 rendering of “California Dreamin’” from José Feliciano that transcends all versions of the song. Blind from birth, the Puerto Rico-born and New York-bred Feliciano -- beautiful to look at with heavy dark bangs, mod wardrobe and daddy-o dark glasses -- had a massive hit with a soulfully flamenco interpretation of The Doors’ signature “Light My Fire.” He had been on the coffeehouse circuit in New York City’s West Village, then released three successful albums in Spanish. He wrote and performed the theme for the typically paternalistic 1970s sitcom Chico and the Man, and is most famous for “Feliz Navidad,” a holiday standard -- itself covered by everyone from the cast of Glee to Celine Dion to Luciano Pavarotti -- he wrote and recorded in 1970. “Do you know, do you realize what you’ve just done? You have created a commotion here.” former New York Yankee and Hall of Fame broadcaster Tony Kubek “I owe a big debt to José Feliciano,” songwriter and Doors’ member Robby Krieger said in 1994. “When he did it, everybody started doing it. He did a whole different arrangement.” Released only a year after the Doors’ original, the song turned Feliciano immediately into a star. “California Dreamin’” was the B-side of “Light,” and radio stations played it as much as the Doors’ cover. He was a phenomenon. The tempo of Feliciano’s “California” is far more slow than the Mamas and the Papas’ version (which itself is not quite the original). And when he says he’d be safe and warm if he “was in L.A.,” it’s a Spanish-inflected “Ellay” and calls to mind the palm trees dotting the barrios and middle-class enclaves of Central Los Angeles as much as the ones gracing Malibu, California. The original lyrics, by John and Michelle Phillips of the Mamas and the Papas, are, I got down on my knees / And I pretend to pray. Feliciano changes this to and I began to pray, and the song is lifted by this humility from the narrator. There’s no shame in disenchantment, in pretending to pray. While we still have it, freedom of religion is of course as much about not worshipping, or performing faith as it is about practicing it. But to actually pray, in a state that used to be mostly-Catholic Mexico, is a knowing script-flip. As are his soulful transitions from American English verse and chorus to Español ad-lib at about the halfway mark. It’s a seamless joining. Feliciano is not Mexican, but this is a Latino singing quite literally about wanting California, and about feeling California. Feliciano moors “California Dreamin’” to the state’s pre-American era, and makes the tremulous state steadier somehow, and more true. Plus his opening chords are deeply Spanish, and as John Phillips has said about Feliciano, “The way he plays the guitar, it’s like the guitar must have been his friend.” The stunningly beautiful song functions as a knotty take on “home,” and “country,” and the success of it, as well the success from covering “Light My Fire” -- two massively popular, acclaimed rock singles -- likely gave him the courage to reimagine “The Star Spangled Banner.” José Feliciano was 23 when he walked onto old Tiger Stadium’s left field with his guitar and his guide dog Trudy. It was a sunny day, Game 5 of the 1968 World Series in Detroit -- Tigers vs. the defending St. Louis Cardinals and the Cards were up, 3-1. Vietnam roiled; Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy had been killed; and Gov. George Wallace of Alabama had gained popularity on a platform of “segregation forever.” Washington, D.C.; Chicago; Baltimore -- aflame with discontent. Tiger Stadium, from the tape, seems an isle of white-culture-dominated America girding itself for the poli-cultural battles it would have with the future: not just an MLB in which 30 percent of the players are of Latin descent, but a president with the middle name of Hussein, a first lady who knows all the Missy Elliott lyrics, and an NBA (integrated in ’47) that is 75 percent black. That day at Tiger was a kind of bouffant and Brylcreem moment common across the United States -- looks all Mad Men-ish in the photos, but was of course overripe with exclusion. And as that well-constructed vibe rots and recedes, still it pushes back, pasting itself to the future with spit and glue, a tall and janky wall in the face of progression. José Feliciano's version is, in his own words, “slow and meaningful.” Tony Spina Collection/Walter P. Reuther Library/ Wayne State University Batter up, though, right? But before we get started, a nice Spanish guy who sings rock songs has been invited to perform -- in fact by beloved Tigers radio broadcaster (and sometime songwriter) Ernie Harwell. Detroit was still recovering from a summer of ’67 uprising that had lasted five days. Persistent segregation and police brutality were cited as causes. Forty-three people died. Harwell had booked Marvin Gaye to sing “The Star-Spangled Banner” for Game 4. This was Gaye’s clean-shaven, “Ain’t Nothing Like The Real Thing,” Tammi Terrell era, and the hometown hero, to cheers, had taken a traditional route. In this era of assassination and pressured integration and -- Stop / Hey / What’s that sound? -- black music continuing to prove itself the sound of young America, what could go wrong when it was Feliciano’s time to be an artist and interpret a poem written (by a man with a strong distaste for blacks) in 1814 and set to music in 1931? What could go wrong if Feliciano, who “wanted to sing an anthem of praise to a country that had given my family and me a better life,” chose to resist the rockets’ red glare? Feliciano’s lean and gloriously singable version of the national anthem is, in his own words, “slow and meaningful.” It’s also yearning and plaintive. He is America Dreamin’ and he nailed it, as Trudy the smooth-haired collie stood by. The Tigers and the Cards were along the baselines, and the small band crowded behind Feliciano appears only mildly confused as he plays his guitar and sings with an intentional lack of bombast. The rendition has been described as “groovy,” “notorious,” “a fiasco,” “Latin-tinged,” “personal” and “controversial.” People complained that his version was “unpatriotic, a desecration.” The Detroit Free Press called Feliciano’s performance “a blues version” that hit an “unresponsive chord.” In truth, it’s ethereal. Feliciano’s October 1968 version of the national anthem is too fine for this world. And when he arrives, beseechingly, at the home of the brave, it’s as if he wants us all to live up to that historic or imagined courage -- and you can hear no applause or other kind of affirmation from the stands. Instead a kind of mass, low grumble emerges from the crowd. There was loud booing. “Before I had finished my performance,” Feliciano said in an undated interview, “I could feel the discontent within the waves of cheers and applause that spurred on the first pitch -- though I didn’t know what it was about.” Veterans apparently threw shoes at televisions. “Soon afterwards I found out a great controversy was exploding across the country because I’d chosen to alter my rendition of the national anthem to better portray my feelings of gratitude.” “Do you know, do you realize what you’ve just done? You have created a commotion here,” former New York Yankee and Hall of Fame broadcaster Tony Kubek said to Feliciano right after the performance. “The switchboard was deluged by calls. I mean you’ve created a real stir.” Feliciano said he was surprised. “Tony patted me on the back and said, ’Don’t worry, kid, you didn’t do anything wrong. I really enjoyed the way you did ’The Star-Spangled Banner.’” “After that happened,” Feliciano said, “everything that I was doing, stopped. Radio stations stopped playing my records. It took me a long, long time, and even to this very day...” The tape ends. Feliciano doesn’t say what it took him a long to time to do. He doesn’t mention, that Harwell -- a former Marine who was called a traitor and a draft dodger and a communist, and who came close to being fired for the booking -- said at the time that “a fellow has to sing it the way he feels it.” Feliciano doesn’t mention on camera that an unauthorized recording of his rendition hit Billboard’s charts. And though the major Detroit stations didn’t play his version of the national anthem, within two weeks, the song had sold almost 50,000 copies in Detroit alone. Perhaps Feliciano means that even to this very day he can’t believe how people responded as he sang his 23-year-old heart out. Maybe he means that even now, in his 70s, as he lives in Connecticut with his wife and continues to record and tour, that he can rest on laurels that include 85 million albums sold worldwide. He can bask in the glow of eight Grammy awards -- including for Best Pop Song for his “Light My Fire,” as well as for Best New Artist in 1969. Perhaps Feliciano was about to say that it took him a long time to realize his own influence on interpretive artists such as Jimi Hendrix in 1969, Gaye in 1984, and of course Whitney Houston in 1991. Maybe he was going to tell people that he is an artist, and he is sensitive about his “Feliz Navidad.” Best would be if he was about to remind folks that he takes pride in creating art about home being a never-ending quest for that which may never be truly seen -- or even felt -- except for on our most glorious or horrific days. And maybe, just maybe, as he stood at AT&T Park on Oct. 14, 2012 before Game 1 of the National League Championship Series, Feliciano thought to himself that this might be heaven, or it could be hell. It was forty-four years later -- San Francisco Giants vs. the St. Louis Cardinals -- and he was singing again at a postseason game our official national anthem in the manner of his very own self. And there’s no doubt José Montserrate Feliciano García heard the voices calling, from far away. The cheers for him at AT&T park were loud, proud, and unceasing. Those voices matter not nearly as much as one’s own, but can as a chorus of belated praise feel deliciously sweet. Almost as if one is dreaming. It’s a lovely place. It's a lovely place. James Cushman As fans rose to their feet for the national anthem at an Amherst Regional High School girls’ volleyball game in October, 11 Hurricanes players went down on one knee, placed their hands on their hearts and directed their eyes to the flag. One player remained on her feet. At the end of the line of players stood senior Megan Rice, one hand on her heart, the other hand on the shoulder of her kneeling teammate Claire Basler-Chang. “I know that there are injustices; that’s just not the way I’m going to express it,” Rice said. “But I totally supported my teammates and was proud of them for being able to do that and stand up for what they believe in.” The Amherst volleyball team began kneeling during the national anthem at a road game against Minnechaug on Oct. 7, 2016, joining the nationwide protest begun by NFL quarterback Colin Kaepernick against the treatment of minorities in the U.S. But Rice continued to stand. She says that, because of her grandfathers, both of whom served in the military, and her father, a former member of the Army who’s now a police officer, she’s uncomfortable with joining her teammates’ protest. Rice also says she doesn’t view kneeling during the national anthem as an effective method of protest. “I have huge respect for the national anthem and the flag, I don’t really think that kneeling during it is a good way,” Rice said, adding that she thinks walkouts are a more practical method of protesting -- such as the one organized at her school after the election of Donald Trump -- because walkouts don’t have any inherent disrespect toward the flag or veterans. The team’s idea to start kneeling during the anthem began at a sleepover earlier in the season, one that Rice couldn’t attend. But she said she came to the decision to remain standing easily. “I definitely thought about it a lot,” Rice said, “but I never thought that I would kneel.” That doesn’t mean she wasn’t worried about how some of her teammates might react. “At first I was kind of nervous, like, ’Oh my god, what are my teammates going to think?’” Rice said. “They’re really passionate about this, and I respect them for that, because they all are passionate about the issues they believe in. “But after the third game we did it, I was actually pretty comfortable because I knew that they weren’t judging me. And I knew that my family and friends supported me in my decision, just as I supported my teammates’ decision, even if I don’t agree with it.” On the court, teammates look to Rice, an outside hitter, to end rallies and earn points. She was successful last season, tallying 225 kills in 24 games, leading the team. And while Rice’s decision to not take part in the protest had the potential to disrupt the team unity, every player said it didn’t. “I was fine with it. It isn’t a knock toward her, we don’t hate her because of it,” teammate Teya Nolan said. “We respect her, and we feel that just because she didn’t kneel doesn’t mean that she doesn’t support what we’re doing.” Coach Kacey Schmitt, who also didn’t participate in the anthem protest, said she initially felt concerned that Rice would feel isolated from the team, so she appreciated that they found a way to include Rice by connecting with her physically. “That’s why they talked about holding [Rice’s] hand to show we’re still unified, because guess what? You can have this opinion and I can have this opinion, and we can still like and respect each other,” Schmitt said. “That’s the way the world should be.” Still, the Hurricanes have received quite a bit of backlash, particularly online. Comment sections of articles about the team and posts on social media sites have amassed opinions galore, including from some who have said the team should be expelled. Rice said that, while she and her teammates have paid attention to some of the criticism, they’re trying to just focus on volleyball. “We definitely get a good laugh at some of them, but we can’t take it to heart or anything, so it doesn’t really affect us,” Rice said. “We’re just like, ’Oh, these people are ignorant and aren’t educated on the issue.’” Rice said her own father initially wasn’t happy with the team’s decision to kneel during the anthem. “The first game it happened, my parents didn’t really know it was going to happen, so my dad was really mad. But eventually he kind of just accepted it and understood that this is how the team feels and they want to show everyone how they feel,” Rice said. “But they were all proud of me for standing up for what I believe in and not going with the crowd and kneeling with my team.” The anthem protest and its ensuing backlash didn’t affect the team’s play on the court at all, as the Rice-led Hurricanes finished the regular season with a record of 20-0, losing just two sets all season. George Rose/Getty Images You have to understand. You have to remember. This is 1991. Before six people died in the World Trade Center bombing. Before 168 died in Oklahoma City. This is before 111 individuals were injured by a bomb made of nails and screws at the Atlanta Olympics. Before backpacks stuffed with pressure cookers and ball bearings blew limbs from people at the Boston Marathon. Think back. This is the tippy-top of ‘91. Way before Connecticut elementary school classrooms in Newtown were strewn with bullets. Before a Colorado theater was tear-gassed and shot up as The Dark Knight Rises began. Before 18 people were shot in an Arizona parking lot, along with a congresswoman who took a bullet in the back of the head. You have to understand. This is before a young married couple in combat gear killed 14 at a holiday party in San Bernardino. This is a generation ago. A full decade before the United States of America came to a brief but full stop -- 2,977 people dead and more than 6,000 injured in three states. This was before three New York firefighters raised a star-spangled banner amid the sooty rubble of ground zero. In 1991, ground zero was just downtown Manhattan. If you were alive -- if you were over the age of 5 -- you must make yourself remember the time. In 1991, people are jittery, but no one stands in line in bare feet at airports. There are no fingerprint scanners at ballparks. This is, like, pre-everything. There’s no Facebook -- barely a decent chat room to flirt in. The Berlin Wall? Buzz-sawed, climbed over and kicked through. Mandela is free, and Margaret Thatcher is out. This is one-way pager, peak Gen X quarter-life crisis time -- and it wasn’t called a quarter-life crisis back then. North and Saint West’s late grandfather had not yet read his friend’s letter to the world: “Don’t feel sorry for me,” attorney Robert Kardashian said to flashing bulbs. “Please think of the real O.J. [Simpson] and not this lost person.” This is the year Mae Jemison preps for the Endeavour, Michael Jordan is ascendant and In Living Color and Twin Peaks stamp the kids who make prestige TV glow in 2016. Beyonce is in elementary school. Steph and Seth Curry are in a Charlotte playpen. Barack Obama is the first black president -- of Harvard Law Review. The (pre)cursors are blinking. “This will not stand, this aggression against Kuwait,” President George H.W. Bush says in August 1990, and by the dawn’s early light of Jan. 17, 1991, a coalition of countries led by the United States drops real bombs on real people and real places in real time on four networks. This was the first Gulf War. There are no color-coded threat level advisory posters on airport walls, but the State Department and the Secret Service agree: The possibility of a terror attack is high, and Super Bowl XXV -- the Giants vs. the Bills, scheduled just 10 days later -- is a soft and glaring bull’s-eye. The Goodyear blimp? Grounded. A Blackhawk patrols instead. Commissioner Paul Tagliabue’s annual Super Gala gala? Canceled. Concrete bunkers gird the parking lot of old Tampa Stadium, and a 6-foot-high chain-link rises quickly behind that. Canines sniff chassis, and ushers wave metal detectors. SWAT teams walk the stadium roof with machine guns. Alternate dates, due to a fear of mass casualties, are considered. For a Super Bowl. “[It] was the shape of things to come,” former defensive back Everson Walls recalled in 2013 for USA Today. “The security was incredible. I think that’s the first time they checked bags and really were concerned about terrorist threats.” It was tense. “Players were discussing privately if there would be a draft,” former Giants tight end Howard Cross said last year in the New York Post. “And whether our younger brothers might be drafted.” There is a ghost game hovering too -- the one played two days after President John F. Kennedy was assassinated in 1963. It is known as the NFL’s “mourning game” and opened with a lone bugler playing taps. Pete Rozelle was ravaged in the media for going through with it. He’d struggled with the decision, and it haunted him his whole career. But Commissioner Tagliabue will not have the regrets of his predecessor. Tagliabue -- a Jersey City basketball-playing attorney who’d represented the league against the USFL -- arrived at Super Bowl XXV in a flak jacket. And he had Whitney Elizabeth Houston. By slowing the song down, Whitney amplified its soul. She made it the blues. Gin Ellis/Getty Images Houston was 27 when she sang “The Star-Spangled Banner” at Super Bowl XXV. She was already the first artist in history to have seven consecutive singles go to No. 1 on Billboard’s Hot 100 pop chart. This Whitney data, of course, does not yet include the zeniths and descents of the second half of her recording career. It doesn’t include the impact she made on-screen in (and on the soundtracks of) 1992’s The Bodyguard, 1995’s Waiting to Exhale and 1996’s The Preacher’s Wife. It doesn’t quantify, because there is no quantifying, the influence she continues to have on Beyonce Knowles Carter, Adele Adkins, Alicia Keys, Lady Gaga and other pop singers who rose in her wake. It can’t articulate the profound relief she granted black teens in the mid-1980s. Just the sight of her, onstage, on MTV, on an album cover -- Houston was proof of life. It became easier for black girls in particular to flex, to breathe -- to revel in visibility and possibility. Houston wanted more than mainstream pop success. She wanted mainstream pop equality. “Nobody,” she told Rolling Stone in 1993, “makes me do anything I don’t want to do.” And that had become the definition of her relationship with the music business. She’d come by her ambition via nature and nurture and aspired to a level pop playing field that had been systematically denied her forebears. She was earwitness to artists who’d thrashed and thrived in an intricately segregated music industry -- not the least of whom was her own mother, Emily “Cissy” Houston, leader of the pop-gospel Sweet Inspirations, who sang behind Jimi Hendrix, Mahalia Jackson, Bette Midler, Linda Ronstadt, Aretha Franklin and more. Whitney was 6 when the Inspirations were singing backup for Elvis Presley in Las Vegas. “[She] taught me how to sing,” Houston said in 1996. “Taught me ... where it comes from. How to control it. How to command it. She sacrificed and taught me everything that she knew.” Whitney’s distant cousin is pioneering operatic soprano Leontyne Price -- one of the first black singers to earn global acclaim in an art form still using yellow- and blackface in 2016. Whitney’s first cousin is Dionne Warwick, who in partnership with Burt Bacharach (and in stride with Nancy Wilson) crystallized the acutely talented, crisply enunciated, pretty and sexually hushed black female pop star prototype that Whitney, for the first few years of her career, clicked right into. The fashion model’s body type. The disciplined tamping down of racial and class signifiers. The gleam in her eyes and smile that said dreams are real. You have to remember. She practiced for Super Bowl XXV. In a demure fur hat and with a case of nerves, Houston sang the national anthem at a Nets-Lakers game in New Jersey early in Kareem Abdul-Jabbar’s 1988-89 retirement season. And she was in even better form for a February 1989 performance of “One Moment in Time,” a song she recorded for the 1988 Summer Olympics Album. Houston wasn’t featured in the video for the worldwide hit, but onstage at the 1989 Grammys, she made her ownership of the song clear. On a large screen were slow-motion shots of triumph -- doves fly, FloJo receives a medal and Greg Louganis is poised to back-flip. The screen rose as Houston, in a white gown, stepped out with aplomb. There was a tiny cross at the base of her throat and a full orchestra in shadow behind her. “You’re a winner,” she belted, “for a lifetime.” And then she allowed herself the tiniest of kicks -- of church -- and a step forward. And as she sang the words “I will be free,” three times in a row, in three different ways, the audience leapt to its feet. You have to understand. Key to American blues is the notion that by performing them and by experiencing them being performed, one can escape them. “I will be free,” sang this black American woman to a mostly white, tucked-in-tuxes audience attending an event at which black achievement has been and remains segregated and minimized. This is our most familiar pop dance. This is white American affluence being comforted by the performance of black freedom -- and so, feeling forgiven. The polished intonations. The buffed exertion. The testimony. This is the conflation of mass sport and mass music. This is bodies and souls at work. This -- one of America’s most influential creations and biggest imports -- is the uplift of big blues. Jim Steeg was, for over 25 years, in charge of the Super Bowl for the NFL. Four years ago, he recalled the lead-up to XXV’s opening ceremonies for SportsBusinessDaily.com: “In early January ... our coordinator of Super Bowl pregame activities Bob Best ... produced a recording of the Florida Orchestra for national anthem producer Rickey Minor. ... A week later, Minor flew to Los Angeles to have Whitney record the vocal track. Amazingly ... it was done in one take.” Yes -- Whitney Houston’s version of “The Star-Spangled Banner” was prerecorded. “There’s no way to rehearse the sound of the crowd ... coming at you,” Minor said years later. “You don’t know where the first note begins.” The NFL had no qualms about the song being prerecorded, even if Houston would be criticized for it. The NFL’s issue was with the meter. “The Star-Spangled Banner” is written in 3/4 time -- not quite brisk, but waltzy. Houston and vocal arranger Minor, as well as bassist-arranger John L. Clayton, changed it to 4/4, slowing it down. “All was in place for what many of us thought would be one of the greatest versions of the national anthem ever performed,” Steeg said. “Then on Jan. 17,” as Steeg further recalled it, “senior executives with the NFL asked to hear the recording. A tape was overnighted to Buffalo, where the AFC championship game was played. The next day I was told the version was viewed as too slow and difficult to sing along with. Could I ask to have it redone.” Perhaps the NFL was afraid there would be discontent in the stands, as there had been when José Feliciano dared to find himself and the times in the anthem before Game 5 of the 1968 World Series. So Steeg called John Houston, Whitney’s father and her manager at the time. “The conversation was brief,” Steeg said. “There would be no rerecording.” You have to understand: By slowing it down, Team Houston and the Florida Orchestra -- under the direction of Chinese conductor Jahja Ling -- not only increased the national anthem’s level of technical difficulty, they amplified its soul. They made it the blues. “And now, to honor America, especially the brave men and women serving our nation in the Persian Gulf and throughout the world, please join in the singing of our national anthem. The anthem will be followed by a flyover of F-16 jets from the 56th Tactical Training Wing at MacDill Air Force Base and will be performed by the Florida Orchestra under the direction of Maestro Jahja Ling and sung by Grammy Award winner Whitney Houston.” You have to remember. It’s a fine warm winter night in Tampa. The Giants’ own Faultless Frank is on the ABC Super Bowl team. Every Hall of Fame hair is in place, and there are no signs of the brain trauma that will later plague him. Al Michaels has not yet uttered the phrase “wide right.” Madonna’s “Justify My Love” and Janet Jackson’s “Love Will Never Do (Without You)” are battling on terrestrial radio, and terrestrial radio is the ruling class. There’s no streaming. No YouTube. The iPod is 10 years away. Want to party? Hit the creaky shuffle on your CD player. At Tampa Stadium, the pregame jam is Snap’s “The Power”: It’s gettin’ / It’s gettin’ / It’s gettin’ kinda hectic. It is, in fact. The ESPN team is broadcasting from outside the stadium. As Andrea Kremer reports at the time, “Every single vehicle within 200 feet of the stadium is completely searched. There will be a large, well-rehearsed team in place at Tampa Stadium. And it isn’t just the Bills and the Giants but rather the security forces designed to safeguard the Super Bowl event while trying not to convey undue alarm to fans, or turn the stadium into an armed camp.” “All was in place for what many of us thought would be one of the greatest versions of the national anthem ever performed.” Jim Steeg But there are more than 1,700 security professionals on the grounds. And if it seems every person is waving a tiny U.S. flag, that’s because a tiny U.S. flag has been placed on every seat. The field is a kaleidoscope of honor guard uniforms and team uniforms and kids doing a red, white and blue card stunt. Central is the entire Florida Orchestra -- standing in full dress, signaling serious and formal. Then Whitney Houston steps onto a platform -- it looks to be the size of a card table -- in a loose white tracksuit with mild red and blue accents. She has on white Nike Cortezes with a red swoosh. No heels in which to step daintily, and definitely not a gown. Her hair is held back by a pretty but plain ivory bandanna -- there are no wisps blowing onto her face. No visible earplugs to take away from the naturalness of the moment. Everything is arranged to convey casual confidence. Here we begin. Snare drums so crisp. Bass drum so bold. Houston holds the mic stand for a moment but then clasps her hands behind her back -- it reads as clearly as a military at-ease. Her stance says: We came to play. Says, in the parlance of the ’hood, and on behalf of her country: Don’t start none, won’t be none. All we have to do is relax, and we’re all going to win. Like the best heroes, Whitney -- the black girl from Jersey who worked her way to global stardom, made history and died early from the weight of it -- makes bravery look easy. Although the stadium hears the prerecorded version, she sings live into a dead mic. The image of her singing is interspersed with faces of the fans, of the soldiers at attention and of the U.S. flag and flags of the wartime coalition countries blowing in the breeze. She is calmly joyful -- cool, actually, and free of fear. And when she arrives at Oh, say [cymbal] does our star- [cymbal] spangled banner yet wave, she moves to lift the crowd. It’s a question. It’s always been a question. And she sings it like an answer. People were weeping in the stands, weeping in their homes. The song itself became a top-20 pop hit. Folks called in and requested Whitney Houston’s national anthem on the radio. The version NFL executives thought might be too slow, people sang along to as they drove down the street. Super Bowl XXV is defined as much by the launch of Desert Storm and Security Nation and by Whitney Houston as by the game itself. That day was the start of a branding relationship between the armed forces and the NFL that has grown vinelike around a state of perpetual war. Houston is of course gone now, but she remains the ghost in the machine -- memorialized, memed, GIFed and in many quarters damn near prayed to. We have her massive ballads, and her bad reality TV, but her “Star-Spangled Banner” is much the reason for Houston’s continued presence -- she boldly interpolated our anthem and sang it as well as it will ever be sung. Remember? When her version was rereleased in the aftermath of the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks -- Houston gave her fees to charity -- she roused and comforted a nation again. It was the last top-10 hit of her career. Most singers want out of that song. Most reach awkwardly for one note or another, or miss it altogether. It’s not just that the song is a difficult one. It’s difficult in front of people who want to feel the pride in the storybook words. They want to wave their ball caps and whoop in the pause after O’er the land of the free. They want to be landlords in the home of the brave. Whitney’s version made it all absolute, for a moment. Her arms were wide and reaching slightly up at the end, a pose familiar to many Americans, across races. Her head was back, as one’s can be when victorious, and as one’s can be when asking for and ecstatically receiving the glory of God. Bright bulbs flashed and popped off behind her. Floodlights intersected with the hazy Florida sunshine and created stairways to heaven. You could almost walk up there. To where the four war jets are. You have to understand. After Colin Kaepernick protested by taking a knee during the national anthem, the Bulls youth football team in Beaumont, Texas, did the same. Their demonstration spread across the country, which led to their coach's release and forfeiture of their season.Dawn’s Early Light

The meaning of “The Star-Spangled Banner” -- America’s original protest song -- on the brink of its most high-profile performance.

So Proudly

We HailedLeon Bridges, the musical gift descended from the vocal stylings of Sam Cooke and Marvin Gaye -- the whole diaspora of African-American sound -- recorded his interpretation of the anthem.

The Perilous Fight

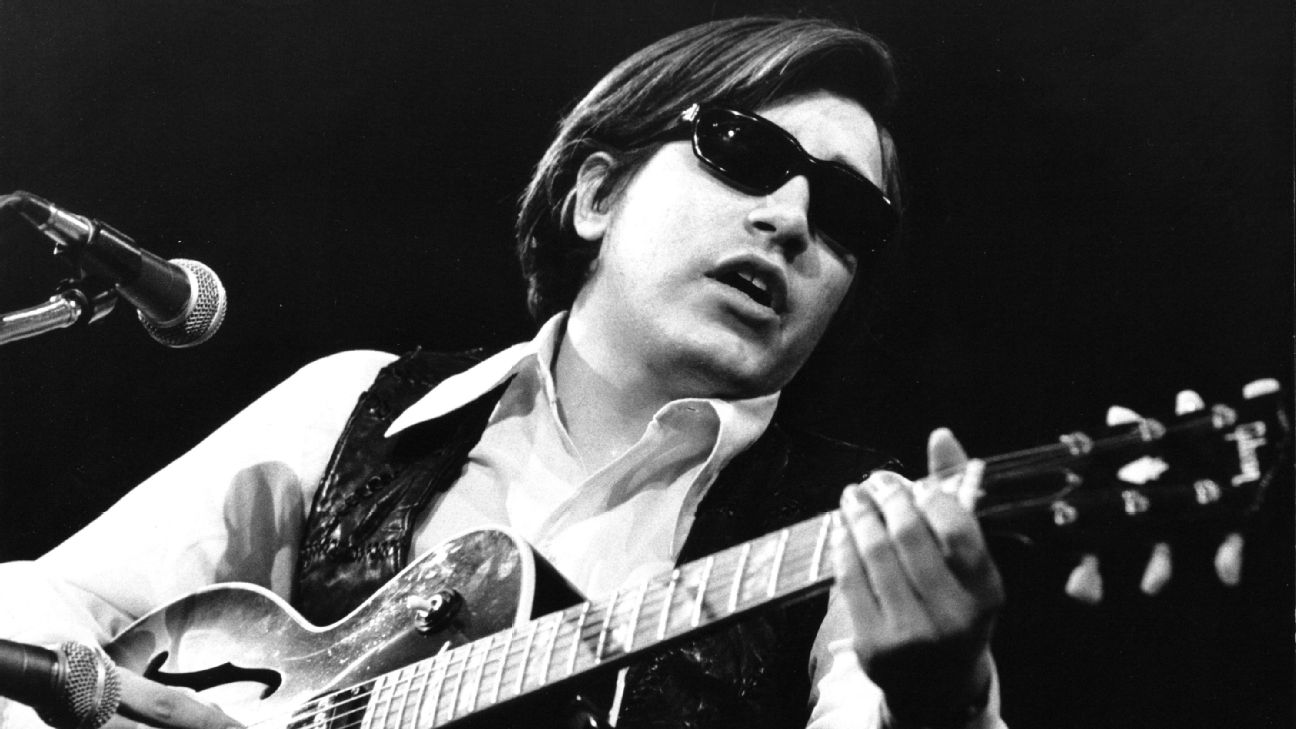

Before singer José Feliciano even finished performing “The Star-Spangled Banner” in Tiger Stadium to begin Game 5 of the 1968 World Series, his career was in ruins.

Our Flag Was Still There

When the Amherst Regional High School girls’ volleyball team started kneeling during the anthem, Megan Rice chose to remain standing.

Star-Spangled Banner

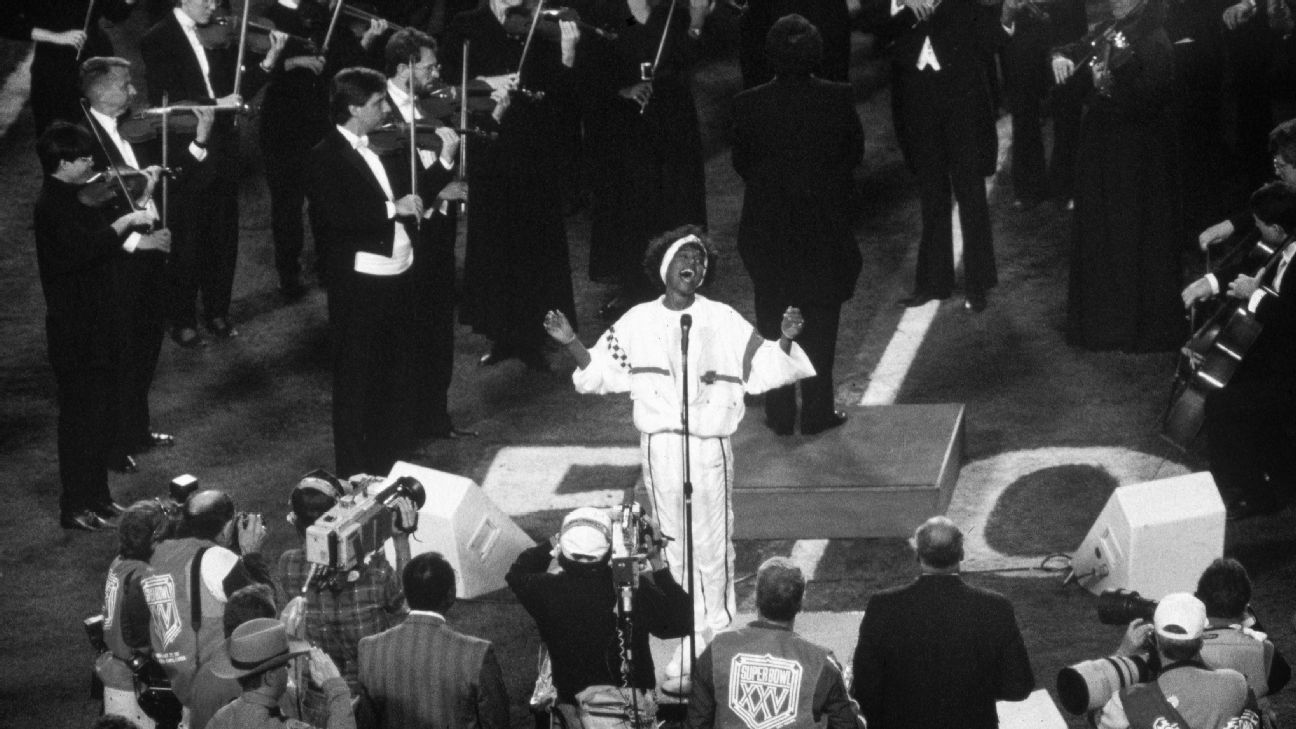

Ten days after the U.S. entered the first Gulf War, Whitney Houston didn’t just perform the anthem at Super Bowl XXV -- she owned it. This is the story of that moment in time.

-- Frank Gifford

Home of the Brave

Inspired by Colin Kaepernick, players from a youth football team in Beaumont, Texas, decided to take a knee. That’s when their season ended but their story began.