Broken Dreams

He burst from the busboy’s closet near the kitchen, maneuvered his way through the crowd as though he were late, and stepped behind the microphone on the tiny stage. Then he began playing, so nervous he looked like he was about to cry. He was thin and waifish, in his early twenties, and strummed his small guitar awkwardly. It was out of tune, which made it sound like a cracked ukulele. His voice cracked too as he sang that first wistful melody:

When I was out in San Marcos, a year ago today / They probably would have put me in a home.

Hmmm, I thought, strangely garbled syntax, a hint of being damaged.

The wildest summer, that I ever knew / I had a flat tire down memory lane.

Now that was a great line. By the time he got to the chorus, I was hooked:

I live my broken dreams.

He jumped into the second song, which was about Casper the Friendly Ghost and seemed to be an allegory about Jesus, or maybe it was just about the cartoon. “This is a joke,” a woman in front of me said to her friend. “Right?”

It was 1985, a club called the Beach near the University of Texas at Austin, and Daniel Johnston was opening for a local band called Glass Eye. I had heard about him, this kid who was handing out homemade tapes with strange cartoons on the covers to anyone who would take them, telling people that he had had a nervous breakdown and that he was going to be famous. Well, everyone in the Austin music scene in 1985 thought he or she was going to be famous.

His third song was called “The Marching Guitars,” which soared over a repeating circle of chords:

No one can stop them / The marching guitars.

The city was full of combustible guitar bands intent on conquering America, and this sounded like an anthem. At least it did to me and the other songwriters, musicians, and scenesters who had come to hear Daniel play. To everyone else, it sounded like he was quite possibly retarded. When he was done with his eight-minute set, he ran from the stage, through the crowd, and back into the closet, pulling the door shut like a coffin.

It wasn’t long after that show, only the third of his career, that Daniel would get the fame he wanted so desperately: MTV, big shows in front of adoring fans, a major-label deal, his artwork hung in galleries in London and Berlin. He would become an underground hero, his songs covered by dozens of fringe indie bands and musicians with names like Wimp Factor 14 and Weird Paul Petroskey but also by some of the biggest bands in alternative rock, such as Yo La Tengo, Pearl Jam, Death Cab for Cutie, and Sparklehorse. The musicians were attracted to the songs themselves, wide-eyed ballads like “True Love Will Find You in the End,” vows of hope in the face of despair like “Living Life,” and desperate songs of fear like “Don’t Play Cards With Satan.” But they were also intrigued by the romance of his mental illness. Daniel is a manic-depressive, and with his stardom have come extended stays in mental hospitals as well as violent psychotic explosions in which he has almost killed himself and others, including his father. Most romantic of all, for the past fourteen years one of the voices of his generation—the generation whose lead singer, Kurt Cobain, blew his brains out more than a decade ago—has been living at home with his parents.

I went to visit him in November. The Johnstons live in a nice ranch house on three acres in the small town of Waller, about thirty miles northwest of Houston. This is conservative country, and the mailbox of the songwriter for the alternative nation had a Bush ’04 sticker on it. Daniel met me at the door, twice as big as the last time I’d seen him and with silver hair cut in no particular style and dark eyebrows. He looked at least 10 years older than his 44 years, and his face seemed pinched in pain or fatigue. We shook hands and he introduced me to his parents, who are both fundamentalist Christians, members of the Church of Christ. Mabel, 81, is sweet and frail and suffers from Parkinson’s. Bill, 82, is no-nonsense but friendly. He is now Daniel’s manager, the only rock and roll handler to ever fly fighter planes against the Japanese in World War II and then accompany his son on tour in Japan 55 years later.

We stood in the living room, where, above the TV, was some of Daniel’s high school artwork—color drawings of Casper and Ratzoid, one of Daniel’s rodent-faced creations, as well as one that read “Artist of the World.” On the walls were photos of him performing at various shows in the nineties. There was also a large, maybe thirty- by twenty-inch photo in a thick gold frame of two boys standing in the shallow water of a lake, one, about three, holding a fishing pole, the line of which had hooked a small toy boat, and the other, about nine, smiling and pointing at the boat. It was the very portrait of childhood innocence and was hung under two track lights, which made it seem like something in a gallery. It was Daniel and his older brother, Dick, on their grandfather’s West Virginia farm, in 1964.

As we talked in the living room, Daniel nervously ran his hand over his stomach. He was dressed in warm-up pants and a thin, well-worn T-shirt that clung to his belly like a balloon; there was a faint gray stain over his chest. He told his parents how he had opened for my band once at the Beach in 1985. We talked about how little money we’d made but how much fun it had been. He said that he had talked his way onto MTV and that he had run around telling everyone he was going to be famous. His parents stood politely by, thin smiles on their faces. Finally the talk stopped, and there was a long pause. “Yeah,” said Daniel, smiling at me, “those were the good old days.” His mother, who had been quiet the whole time, stepped toward the large photo of her two sons, pointing. “Those,” she said, “were the good old days.”

Before the fame and the madness. For Daniel, they have always been connected, something his parents know all too well. And they know that now the fame is coming around again. In September a tribute album was released with artists like Beck and Tom Waits covering their son’s songs. In January a highly touted, million-dollar documentary on Daniel’s life, The Devil and Daniel Johnston, premiered at the Sundance Film Festival. His first album in two years will be out in the summer. And in December a Houston theater company is presenting a rock opera based on his songs. Once again, Daniel’s wishes are coming true, and once again, his weary parents are standing politely by, holding their breath.

Like a Monkey in a Zoo

Daniel was born January 22, 1961, in Sacramento, an unexpected fifth child; the family moved to Utah and then to Chester, a small town in West Virginia’s northern panhandle. His first love was comics, especially the Marvel Comics superheroes like Captain America and the Incredible Hulk. By age eight he was already drawing his own comics, with a cast of characters and a mythology to guide them, a world of good versus evil, informed as much by superheroes as by the dualistic teachings of the Church of Christ. Captain America was there. So were Jesus, Satan, King Kong, and Casper the Friendly Ghost. “I’ve always identified with Casper,” Daniel told me. “I try to be the good guy, and pure.” His comics included his own characters too, playful creatures who would eventually pop up on his cassette covers.

In high school Daniel was a loner and an underachiever who spent more time playing piano and drawing in the basement than hanging out with others. He was depressed a lot of the time, but his parents thought he was just being a typical self-absorbed teenager. Still living at home after he graduated, he enrolled in classes at the East Liverpool branch of Kent State, across the Ohio River. There, almost by accident, he became a songwriter. “What really happened,” he told me, “is I met this girl who was engaged to an undertaker. But she was very beautiful, and I made up some songs just to please her. And she liked them. And I just flipped out. I was at the piano banging away every day, writing songs. And I turned into a maniac and I never gave up, and that’s what really happened to me.” The woman, Laurie, eventually married the undertaker. But Daniel had his muse. His albums are filled with songs to Laurie and to true love. He would sit at the piano, turn on a cheap tape recorder, and play songs about unrequited love, the misery of being a loner, and following your crazy dreams. Then he’d draw. Then he’d go back and record. His friend David Thornberry, who would go down into the basement and draw too, remembers, “He was an obsessive creator, drawing and writing all the time.” Daniel announced that his ambition was to be as big as the Beatles. He was fixated on fame, says Thornberry: “It wasn’t about ‘if I get famous’ but ‘when I get famous.’ He assumed that if he put in the time, tried to be in the right place at the right time, met the right people, it would happen.”

Daniel began putting together tapes of his music; Songs of Pain was the first, and Don’t Be Scared followed. They were strange, low-fi collections, with Daniel banging haphazardly on the piano. Most young songwriters try to be tough, cynical, or something they aren’t. These songs could only have come from Daniel; they were naked and honest, full of longing and need, sung in a high twang that sounded as though his heart were breaking. It was as if he were exposing himself. They were funny too, with titles like “I Save Cigarette Butts.” The melodies were sunny one song and aching the next, the kind of pure pop concoctions that Lennon and McCartney wrote.

With the songs he would also record TV evangelists and conversations with friends. On one, Daniel, in a fake veejay voice, says, “Ah, that was Dan Johnston on MTV . . . Coming up a little bit later, we have some concert news on Dan Johnston.” And he recorded his mother, upstairs and not knowing she was being taped, berating her son. “We just produced a great big lazy bum!” Mabel yells on one, sounding truly anguished. “And you have no shame. You like it that way!” He recorded civil conversations with her too. “I don’t really mean to be depressing in my songs,” he says to her on another tape, in an apologetic tone. “Sometimes they just turn out that way.” Daniel fought often with his parents, who were bewildered by his drawings and his music and thought he was immature and manipulative. He was torn between their path—God’s path—and the one he was just beginning to figure out—the artist’s. He wouldn’t get a job. He had “grandiose ideas” about wanting to be a famous songwriter, Mabel would later write to a psychiatrist. During this time Daniel had periods of elation, when he would obsessively write and draw, followed by descents into a pit of despair. His parents didn’t know it, but his teenage angst was crossing the line into manic depression.

Daniel dropped out of Kent State in 1982 and the next year moved to Houston to live with his brother, Dick. There, using a toy chord organ and a Smurf ukulele, he recorded his next tape, Yip/Jump Music, in Dick’s garage. After a series of disagreements with Dick’s wife, Daniel moved to San Marcos to live with his sister Margy, where he delivered pizzas, recorded Hi, How Are You, and had a nervous breakdown. When he saw a letter from his mother to his sister that he thought suggested putting him in an institution, he fled town with a carnival, quitting when it stopped in Austin and talking a UT-area church into letting him stay in a back room. It was 1984, and he got a job at a McDonald’s, passing out his tapes to anyone he’d meet there or on Guadalupe Street, the campus drag. “Hi, how are you?” he’d say. “I’m Daniel Johnston, and I’m gonna be famous.”

He found numerous proselytizers in the local music scene, started playing shows, and even got a manager. He also talked his way onto an August 1985 episode of the MTV show The Cutting Edge, which was doing a feature on the Austin music scene. He introduced himself to the world at large by awkwardly holding up his latest tape and saying, in his thin, wavering voice, “My name is Daniel Johnston, and this is the name of my tape. It’s Hi, How Are You. And I—I was having a nervous breakdown when I recorded it.” You can see him, like one of his superheroes, putting on the mask, assuming the character, mythologizing himself. The nervous wreck. The carnival. The breakdown. The cartoons. The woman he loved who would never love him, who had married an undertaker. The songs of terrible beauty, sung terribly. It was all real and it was all a beautiful put-on.

See Satan Die

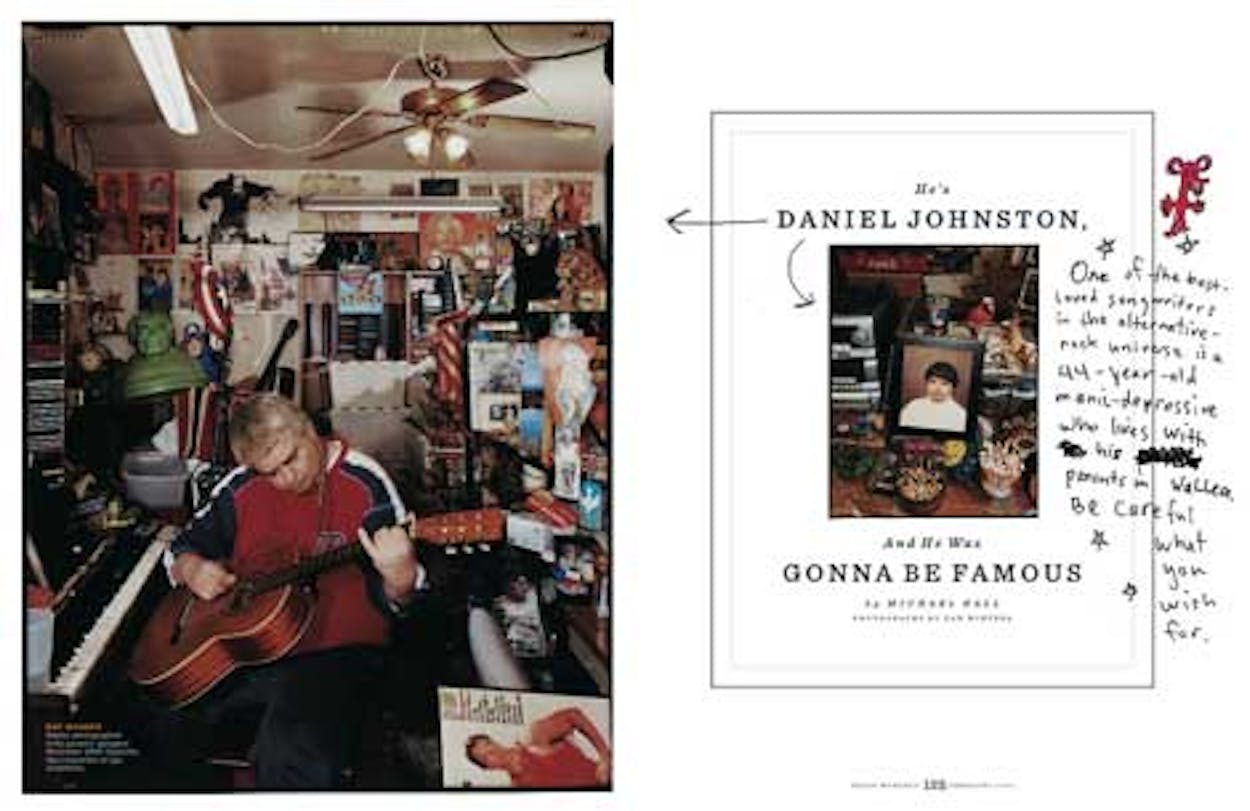

The Johnstons have a two-car garage. On one side is the family car and on the other is Daniel’s studio. The walls are covered with photos, paintings, and clippings: the Beatles, Star Wars, King Kong, Godzilla, Batman, the Monkees, Captain America, anonymous fifties pinup girls, Marilyn Monroe. There’s a photo of Bill and Mabel in there, as well as some of Daniel’s album art. Shelves hold armies of toy dinosaurs, little dolls, little Beatles. There’s an old piano against the wall and a table on which sit a boom box, a turntable, an ashtray, and a couple of cups of fresh cola, with no ice. On a shelf are more than a dozen notebooks filled with songs; on the piano are cluttered heaps of cheap cassettes. There’s also a microphone on a stand and a little Marshall amp. There’s a rhyming dictionary and a Bible. The rug on the floor is moist with grime.

The garage, his friend David Thornberry says, is a modern-day version of what Daniel had in his West Virginia basement. This is where he goes every day to write music and listen to it and to dream of recording some of the hundreds of songs he has lying around. One afternoon, the two of us sat in his studio and Daniel played me some of his unreleased songs on his stereo. The first was from an album he’s been working on with producer Brian Beattie, who was in Glass Eye and who has been recording Daniel for more than a decade. “Wishing You Well” is a tale of obsession and love, with Daniel singing a beautiful, straining melody to Laurie, whom he hasn’t seen in eighteen years: “And I love you, you’re my wife.” His once boyish voice sounds tired now. As Daniel listened, eyes closed, he held a menthol Kool 100 in his mouth with the fingers of his right hand, moving it barely in and out for a minute or so directly under his nose, the ember occasionally flashing orange as he inhaled. The ash fell directly onto the stain on his chest and sat there.

Daniel searched through a pile of tapes and played a song from a session with a band he has with some local guys, Danny and the Nightmares. It’s a rock song with buzzing guitars and Daniel singing verse after verse about obsession and love.

I became a monster in my mind

Suddenly I wasn’t kind.

“This is a great song, I think,” Daniel said.

“What’s it called?” I asked.

“‘See Satan Die,’” he said and chuckled. Then the chorus finally came, repeated over and over:

Love is all there really is

See Satan die!

When the song was done, he dropped the cigarette into a bowl and lit another. He played a third song, with him singing in a high falsetto a tale of obsession and love. The chorus went:

I feel like Lucifer tonight

What have I done?

“I’m guessing you haven’t played this for your parents,” I said.

He laughed. “I guess not. ‘Hey, Mom! Listen to this!’ Yeah, I’ve got to be careful what I play for my parents.”

Daniel’s garage studio is the perfect teenage-boy clubhouse for an imperfect middle-aged teenager, one who sits around all day listening to records and CDs, still thinks of women as girls, and still looks at love the way a teenager looks at his first love, as the one person who will finally understand him. But Daniel has plenty of 44-year-old smarts too. He’s lucid and funny. He has a great memory for historical detail, even if he can’t remember to take his medicine. He knows his reputation and what people think of him (he once wrote a song called “Daniel the Idiot Savant Rock Star”). He’s aware of how strange it is that he still lives with his parents, but he’s also aware of how much trouble he gets in when he leaves their care. And he was certainly aware that I was watching his every move and inhalation, recording them in my notebook. He’s used to that by now.

Devil Town

The trouble for Daniel began with the drugs. A devout Church of Christ member when he arrived in Austin, Daniel didn’t even drink, much less get high (he told a prospective girlfriend that he couldn’t have sex before marriage). But for whatever reason, either because he was swept away in the general enthusiasm of the time or to impress a girl or to break further from his parents, he began smoking pot and then taking LSD. His fragile mind began to slip. Daniel took a panicked bus trip to Abilene to visit his sister Sally and had a terrible vision on the way back of skulls and blood and Satan lying in wait. “The devil has Texas!” he wrote about the trip in “Spirit World Rising.” Back in Austin, Daniel was consumed with fear. He thought his manager, Randy Kemper, was possessed by the devil and hit him over the head with a pipe, putting him in the hospital. A few nights later, after taking acid, Daniel wound up in a creek near UT, singing hymns and calling to Jesus, trying to wash his sins away. The police came and took him to the Austin State Hospital; it was his first stay in a mental institution. Jeff Tartakov, a friend who had helped Daniel set up a publishing company for his songs, went to visit and was told by the staff that Daniel was suffering from two delusions: that there was going to be a military takeover on Christmas Day and that he had to get out of the hospital by Sunday because he was going to be on MTV that night. “I said, ‘Well, I don’t know about the first,’” Tartakov told me, “‘but the second is true.’” It was Daniel’s second appearance on the music network. At a court hearing in the hospital, Daniel said he’d made a terrible mistake taking LSD and promised that he’d never take it again. He was released.

Afterward, thinking that his tapes and drawings were evil, he threw them into a Dumpster. Tartakov fished them out and called Daniel’s father, fearing that Daniel might commit suicide. Bill flew down in his private plane and took his son back to West Virginia and put him in a hospital, where he was diagnosed with schizophrenia. Daniel spent a year in bed, taking the heavy-duty antipsychotic Haldol, ballooning to more than two hundred pounds, and thinking he was going to hell. In April 1988 he stopped taking his medication and headed for New York, where he hung out with indie rock stars in Sonic Youth and Galaxie 500 and recorded some of the songs he had been writing, such as “Spirit World Rising,” “Don’t Play Cards With Satan,” and “Devil Town.” He also spent time in a homeless shelter in the Bowery, was arrested for drawing Christian fish symbols on the base of the Statue of Liberty, and spent a night in Bellevue after a street altercation. Eventually he got a bus ticket and returned home, where his parents put him back in the local mental hospital. They didn’t know what to do with their son. “We were dumb enough to think he was just spoiled,” says Bill. But they took him to new doctors, and Daniel was finally diagnosed with manic depression, an affliction that causes sufferers to experience wild, high moods followed by dark, low ones. It is caused by a chemical imbalance in the brain, and it can’t be cured, only treated with different medications to try and restore the proper balance. So Daniel got some new meds.

Meanwhile, the notoriety had helped make him a hipster darling. In 1988, after a recording project in Maryland, Daniel returned to Chester in the middle of the night, stopping within sight of the funeral home owned by Laurie’s husband, where he began shouting. An elderly woman yelled out of her second-floor apartment and told him to shut up, and Daniel, thinking she was possessed by Satan, broke into her apartment. The terrified woman fell out of the window trying to get away from him, breaking both her legs. In the aftermath, Daniel, back in the hospital, wrote a fifty-page letter to Tartakov in which he said that he was going to be bigger than Vincent van Gogh. He eventually felt well enough to play at the 1990 Austin Music Awards. It was to be a comeback, a homecoming, and Bill flew Daniel down in his plane. Daniel, though, had once again quit taking his medication and was nervous. The devil, he thought, was waiting for him in Texas. Though the show went well, the return flight to West Virginia was a disaster.

One afternoon, while Daniel was off shopping, Bill, the decorated fighter pilot, sat in his La-Z-Boy recliner in the living room and told me the story of that flight as if he were telling a tale of one of his sorties against the Japanese. “We were in the air just south of Little Rock, 6,500 feet up, and Dan said, ‘Dad, I’m gonna be sick.’ He reached over and turned the engine off. I turned the key back on. Then he threw a can of pop out of the window. I said, ‘Dan, you can’t do that.’ He saw a lake off to the right and told me, ‘Land there!’ I said we couldn’t land on water. He had been reading a Casper comic, and on the cover was Casper in a parachute, and he yelled, ‘Let’s bail out!’ The next thing I knew, he had turned off the ignition and thrown the keys out the window. So now I got a dead engine. He grabbed the controls, and we started going down. I tried to grab them back, and we wrestled with it and ended in a tailspin, going straight down. I could see the tall pines through the window.”

Mabel, sitting on the couch, interjected: “Bill yelled, ‘You’ll kill us!’ and Dan yelled back, ‘I can’t die!’ That was his delusion.” Her son, perhaps convinced that he was Captain America, was trying to prevent his father, who may or may not have been under Satan’s orders, from killing him.

“At the last minute,” Bill continued, “he let go, and I was able to level out above the trees. I headed for a clearing but came up about one hundred yards short. We crashed into the tops of the trees and stopped sixty feet up and then fell straight down. After we got out of the wreckage, a farmer came running up to help, and Dan threatened him. I said, ‘Leave him alone. He’s out of his mind.’”

“You want to see a grown man cry,” said Mabel, her eyes wet and her voice shaking. “Bill cried, to think a son did that. By the grace of God they were hardly touched by injuries. One of the things Bill said after the crash was, ‘We’re not going to have Dan stay with us anymore, and we will be happy.’ But I knew we wouldn’t be happy. Dan needed us. We had promised all our children we’d be there for them. And it was Bill who made arrangements to bring him home.”

The Story of an Artist

Every day, Daniel sits in his parents’ dining room and draws his old friends: Captain America, Ratzoid, the Incredible Hulk. He colors them in assembly-line fashion—red, then green, then blue, spending half a minute on each one before moving on to the next. They aren’t as carefully shaded as the older ones, and a folder of 25 will be done in a couple of days. His father and brother give Daniel $10 for each drawing, which he uses for cigarettes, soda, candy, CDs, and DVDs; they sell them on the Internet for up to $150 each. That money goes into a savings account.

With a few exceptions, Daniel has been living and working at home since 1991, when the three Johnstons moved to Waller. Bill and Mabel wanted to be near their other children—a businessman and three schoolteachers—who were starting to give them grandchildren. Once in Texas, their youngest, the odd one, the bachelor artist, began receiving attention again. He had his first one-man art show in Zurich, and the French Lyon Opera Ballet toured Europe and New York with a show based on some of his songs. In 1992 Kurt Cobain, the biggest rock star on the planet, wore a “Hi, How Are You” T-shirt at the MTV Video Music Awards—and then wore it again and again at photo shoots for the remaining eighteen months of his life. Daniel was so hip that in 1993 Tartakov, then Daniel’s de facto manager, found himself in a bidding war between two major labels, Atlantic and Elektra, for the next album. Daniel, in and out of the Austin State Hospital at the time, turned down the better deal with Elektra, fired Tartakov, and signed with Atlantic. But he was in such bad shape that he could barely play anything in the studio, and the disjointed result, Fun, was anything but. It stiffed, and Atlantic dropped him.

For the rest of the nineties, Daniel’s doctors tried various combinations of drugs, seeking to right the chemical imbalance. Some worked, some didn’t, and some had terrible side effects. In stable periods, Daniel was able to perform again. Producer Brian Beattie released Rejected Unknown on his own label in 1999, and Daniel hit the road, accompanied by Bill, who had become his manager, touring the U.S., though he still had several bad episodes. Finally, in 2002, a new doctor tried a new medicine, Topamax. It worked. “Mentally,” says Bill, “the last two years are the best he’s had since 1979.”

With the stability came, well, stability. “I’m trying to be inspired,” Daniel told me. “I just don’t want to suffer to be inspired.” What, I asked, inspires him? “Girls. That inspires me—to have a girlfriend. Marilyn Monroe. Comic books and movies and records and CDs and DVDs.” On the dining room wall is a drawing of Captain America, Casper, Joe the Boxer, Sassy Fras the Cat, and a couple of other characters from Daniel’s life. “I drew that in the mental hospital,” says the artist. “Some say my art was better when I was crazy. Well, I don’t miss being depressed at all. The depression would be so severe it was just like pain in my brain. Constant pain and depression. It was horrible. It would go away and then I’d be manic—out-of-my-brains happy.” Daniel doesn’t blame the devil much anymore. In fact, Daniel doesn’t even like to talk about him. He blames the drugs and the manic depression for all the trouble: “It was just a chemical imbalance in my brain. But the new medicine has really helped a lot. They finally figured out how to stabilize me, and I just behave myself.” The devil doesn’t have Texas anymore, he insists. “I love Texas. It is God’s country.” Daniel’s faith runs deep; he reads the Bible and goes to church with his parents. And so does his fear of Satan. He’s still fascinated with the dark side of the world, especially the Beast in the book of Revelation: “I’ve always believed the Beast was real.” I asked him how Casper would do in a showdown with the Beast. “I don’t think Casper would stand a chance against the Beast. Nothing can stop the Beast.”

It’s hard to tell if he’s happy; his moods have certainly been leavened by medication, his physical needs met. He depends on his parents for almost everything, even as he bristles at their control—but he’s always done that. He’s lonely—but he’s always been lonely. Daniel talked about his parents’ plans to build him a house on their property, which everyone is excited about. Daniel would like some privacy. Mabel would like to have her dining room table back. And Bill, who does the lion’s share of taking care of Daniel, is just worn out. “It’s sapped our strength,” he told me. “We’re reaching our limit. We’re in our eighties now, and he doesn’t cooperate. Sometimes he acts like he’s ten years old.” Daniel spends too much money on candy and comics. He won’t take his medicine—fifteen pills a day, five with each meal, for manic depression as well as for his diabetes, gout, and a thyroid condition—unless Bill stands over him. “I have to hand them to him and watch him take them,” says Bill. “If I don’t, if he goes to get a glass of water, later I’ll find the pills on the counter.” The day before, Bill had tested Daniel and found his sugar level too high and gone into the studio to ferret out a couple of bags of candy. Bill has other things to worry about too: For some patients, drugs like Topamax lose their potency. “If it starts not to work,“ Bill said wearily, “he’ll have to go back to the hospital.”

But for now, Bill chooses to be upbeat about the documentary, which took three years to make, and about the upcoming rock opera and his son’s ability to cope with the inescapable attention. Daniel’s home now, and he’s medicated. “If it clicks,” Bill says of the next round of notoriety, “maybe we’ll get enough money in the bank so we can hire someone to take care of him. Because we won’t be around forever.”

True Love Will Find You in the End

I drove out to visit Daniel again in December and brought along David Thornberry, who now lives in Austin. Daniel doesn’t get many visitors who are not taking his picture or interviewing him (two weeks later a Dutch public television documentary crew would spend a weekend with him) and was obviously pleased to see his old friend. At lunch they talked about the days in the basement, and after a while Thornberry said, “You seem more like your old self than you ever have.” Daniel replied, “Having you around makes me feel like my old self.” We talked about some of my favorite songs of his. “True Love Will Find You in the End,” he said, was his attempt to write something like Paul McCartney’s “Yesterday.” He said he wrote “Living Life” when his mother wouldn’t let him play the piano on his nineteenth birthday (“You must have been playing in the middle of the night,” said Thornberry). But my favorite is probably the whimsical “Walking the Cow,” with its carnival organ, descending melody, and inscrutable words, written right after he left home:

Try and point my finger

But the wind just blows me around

In circles, circles

Lucky stars in your eyes

I am walking the cow.

Over enchiladas and chips, I sang him the chorus and asked what the words meant. “That was from the little girl walking the cow on the Borden ice cream label,” Daniel explained. “Walking a responsibility is what it means. Everybody has to do it—walk your responsibility, your cow.” And the “lucky stars in your eyes”? “Everybody has that part of the day too. You’re dreaming and you’re feeling pretty good. If it lasted forever, you’d be bored by it. Somebody who dreamed all the time might become sort of, uh, satanic. They’d think they were superior. But a little bit of this and a little bit of that, it’s all right.”

I went home and listened to the song again; Daniel, singing in his little boy’s voice while he bangs on a toy chord organ and sounds like he’s careering down a cliff without brakes.

I really don’t know how I came here

I really don’t know why I’m staying here.

It’s one of those songs that makes you feel happy and sad at the same time.