This piece originally ran in the December 1978 issue of Esquire.

Listen to Ken Auletta discuss this story with David Brancaccio in an episode of the Esquire Classic podcast:

Don't mess with Roy Cohn.

The "21" once did. The restaurant spa of the rich and powerful used to seat Roy in Siberia, upstairs in a corner with the tourists. One day Roy called and made a reservation for four at 8:00 P.M. Purposely arriving ten minutes early, he was brusquely led to his usual far nook. Promptly at 8:00 p.m., the duke and duchess of Windsor entered the room. "Ten captains stood up," as Roy remembers it, and tried to steer the duke and duchess to a choice table. From the corner of the room, Roy waved to his dinner guests. They waved back, pulling away from the captains to join their friend. "Please, Mr. Cohn," the captains beseeched him. "Allow us to give you a more comfortable table." He wouldn't hear of it. "Roy loved it," recalls his boyhood friend William Fugazy. "He fixed them. That was his way of-showing them. Now he gets the good tables."

Today, Roy is holding court at one of his favorite "21" tables, against the wall facing the entrance. where everyone can see him. Captains hover nearby, snapping in light his thick Cuban cigar. A red phone is placed to his right. His legal clients are sprinkled throughout the wood-beamed room, Roy Cohn has reason to be pleased—he has survived more crises than Richard Nixon. In the early Fifties, he was the arrogant red-baiting counsel to Senator Joseph McCarthy, the twenty-six-year-old who threatened "to wreck the Army" if favored treatment was not granted his friend David Schine—Bonnie, Bonnie and Clyde is how Lillian Hellman referred to Cohn, Schine and McCarthy. In the Sixties, he was indicted four times (the first case ended in a mistrial) and always acquitted. He has suffered several judicial reprimands for unethical conduct, had his wrists slapped in civil cases, and been ordered to make restitution. In the Seventies, he has been indicted for violating Illinois banking laws; the Internal Revenue Service has audited his income tax returns for the last nineteen years and seized some of his assets. He has been the target of criticism and innuendo about his ethics, his finances, his personal life. He has even been accused of conspiring to murder a young man. Roy Cohn, it is said, is the personification of evil.

Actually, Roy Cohn personifies the problems of the law. Of all the attributes of a good lawyer, cynicism is certainly among the foremost. How else could one weave a defense for a client who is guilty? Like mock UN assemblies for college kids, one day you argue the Soviet Union's position; the next, the United States', What you say has little to do with what you believe. In fact, convictions can get in the way You're an advocate, not a judge. Your interest is form, not content—the process. Surprising the prosecution, entertaining the jury, flattering the judge, leaking information to the press, figuring out angles, coaching testimony, unearthing sympathetic witnesses, feigning anger or sorrow—they're all part of the game. Roy just plays the game harder, tougher, makes up his own rules. "He does what he has to to win," observes a former associate, comparing him to Richard Nixon's favorite football coach. "It's the George Allen school of law. He'll pull out some plays every now and then that aren't in the book." This has earned Roy considerable notoriety.

NO MR. NICE GUY

The notoriety hasn't hurt a bit. At fifty-one, he has seen his law firm, Saxe, Bacon & Bolan, expand rapidly. Its town house office at 39 East Sixty-Eighth Street is bursting with 42 employees, including 12 lawyers. They have just rented an additional floor at 667 Madison Avenue. His clients include Newhouse newspapers and Conde Nast magazines; the Catholic Archdiocese of New York; the Ford Model Agency; Studio 54; Potamkin Cadillac, Baron di Portanova; the biggest names in New York real estate, including Lefrak, Helmsley, Trump; Louis Wolfson, owner of Affirmed; Warren Avis, as in rent a car; Peter Widener and his sister Tootie, a Main Line Pennsylvania family with coal, rail, and racetrack interests; Jerry Finkelstein, a New York businessman; John Schlesinger, a British investor in South Africa; Carmine "Lilo" Galante, the reputed boss of bosses; "Fat Tony" Salerno; Nicholas "Cockeyed Nick" Rattenni; Thomas and Joseph Gambino, sons of the late Carlo; and a string of hoods; Nathan's Famous; Luca Buccellati, the jeweler; Congressman Mario Biaggi; Mrs. Charles Allen Jr., wife of the chairman of Allen & Company, He has counseled his friend George Steinbrenner, owner of the Yankees. As a favor to his friend Halston, Roy advised Bianca how to handle Mick. He was to be Onassis' divorce attorney against Jackie.

The more publicity Roy generates. the more clients he attracts. Just recently he exploded on the front pages, bringing a stockholder suit against Henry Ford, charging that Ford accepted bribes and siphoned company funds for his personal living expenses. He made the evening news when he appeared, without fee, as the attorney for I. Wallace LaPrade, former head of the FBI's New York office, who was fighting Justice Department charges involving his role in illegal bugging and break-ins. Unlike mast lawyers, he is not press shy. "I'm a ham." he boasts. When gossip columnist Liz Smith reported that Roy was representing Christina Ford in her divorce action against Henry, Christina issued a denial, which Smith duly printed. "Then I had a correspondence with him," says Smith, "where he said he was representing her." She believes Roy leaked the original column item to her through a friend for publicity. Cohn denies it, admitting only that he had met with Christina. He promised to produce the Liz Smith letter to disprove her claim but never did. No matter. "The more you say he's a ruthless bastard," chuckles his law partner Stanley Friedman. "the more it helps." Has publicity, much of it negative, helped? "All of this has done me a lot of good, there's no question about it," admits Cohn. "I'd be a liar if I denied it. It's given me a reputation for being tough, a reputation for being a winner." A former assistant U.S. attorney who still believes Roy should be behind bars puts it another way: "He's the only person I've ever known as a prosecutor who enjoyed being indicted. He enjoys the limelight."

The publicity almost guarantees that Roy's phone calls will be returned. "I can get attention, no question about it," says Cohn. "They know my name. The usual response is, 'What did I do?'" His standard technique is to dispatch a threatening letter on behalf of a client—"Hey. mister. This is now the eleventh hour before the monster strikes!" is how Roy puts it.

"Roy symbolizes viciousness in protecting a client or going after someone who needs viciousness to right a wrong," says Bill Fugazy. He fights his cases as if they were his own. It is war. If he feels his adversary has been unfair, it is war to the death. No white flags. No Mr. Nice Guy. Prospective clients who want to kill their husband, torture a business partner, break the government's legs, hire Roy Cohn. He is a legal executioner—the toughest, meanest, loyalest, vilest, and one of the most brilliant lawyers in America. He is not a very nice man.

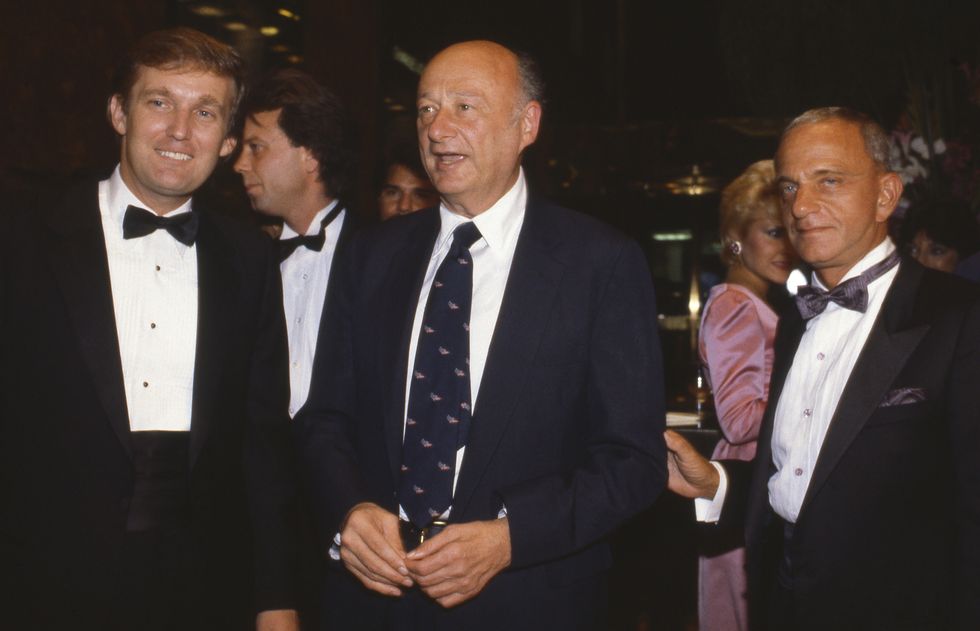

Once when a husband tried to pull a fast one and ordered two moving vans to sneak up to collect furniture at 7:00 A.M., his hysterical wife called Roy. "What should I do?" she screamed. "Sit tight," he calmed her. "I'll call the cops," He had the husband thrown in jail. "I must have had fifty men call me over the years and ask. 'We hear Roy Cohn is going to represent my wife. Would you make sure he doesn't rough us up?'" says Fugazy, "The mere sending of a letter from Roy Cohn has saved us a lot of money," says builder Donald Trump. "When people know that Roy is involved, they'd rather not get involved in the lawsuits and everything else that's involved." Publishers, TV networks, editors, are accustomed to receiving preemptory phone calls or threatening letters from Cohn and cringe at the court costs of taking him on.

POWERFUL FRIENDS

Cohn is a unique kind of bully—fearless. During the Army-McCarthy hearings in 1954, he lunged at and tried to punch his co-counsel, Robert Kennedy. Considering Cohn's lack of agility—at a recent Yankee game when everyone in the box ducked to avoid third baseman Graig Nettles chasing a foul ball, Roy stood up and got punched in the neck—he is fortunate people interceded before he could swing at Kennedy. "I know that if I were in a fight," says publicist Howard Rubenstein, who has his own collection of influential clients, "I'd want Roy Cohn in my corner. I've seen people in divorce fights say, 'Oh, my God, it's Roy Cohn.' It's like in the wild West, when one of the hired gunmen with forty notches in his gun strides into the bar and everyone ducks or says, 'better get out of here.' He's not the Lone Ranger in a white suit. His reputation as a bad guy willing to stand up and fight helps him."

To his clients, Roy is like a faith healer. "He's almost a mother's helper," says builder Sam Lefrak. "He doesn't tell you he's going to lose, like most lawyers." When the federal government was suing the Trump organization for discriminating against minorities in their housing projects, Don Trump searched for a lawyer. "They all said. 'You have a good case, but it's a sticky thing,'" remembers Trump. Then he met Cohn for the first time at a party, explained his predicament, and was thrilled when Roy instantly declared, "Oh, you'll win hands down!" Sitting beside him at "21," Republican socialite Sheila Mosier, whose divorce he is handling, exclaims, "To me, he's like a brother."

Looking at Cohn closely, one is not surprised that "2l" would shove him in a corner. Hooded, bloodshot eyes give him the appearance of a convict. A deep scar wiggles like a river down the center of a thick nose. Lines streak from either side of the nose to the mouth, which he lubricates with lizardlike strokes from his tongue. Short hair hugs his head, which is balding on top. The hairline is neatly shaved to form an arch above his ears, extending down and around the entire back of his head. Two thin, red lines curve around each of Roy's ears, the result, he admits, of cosmetic surgery to correct "bags" and "heavy lines. He looks like a killer. Except for the body and the deportment. He's only five feet eight inches tall, 144 pounds. The suit he is wearing this day is dark blue, slightly tucked at the waist, with a faint stripe. A modest paisley tie fades into a nondescript striped shirt. His mannerisms—the licking of the lips, the waving wrists—are effete.

Roy waves to Leo van Munching, the head of Heineken; Victor Potemkin; Donald Trump; and a procession of friends who flit by. He has always made powerful friends. At the age of ten he was introduced by his father, Al Cohn, a respected Bronx and then New York State supreme court judge, to FDR. Roy, who began speaking at political rallies at the age of nine, promptly informed the President he agreed with his court-packing schemes. When Roy was a teenager, Dora and Al Cohn insisted that their chubby—and only—son attend their dinner parties with Ed Flynn, Carmine DeSapio, and other movers and shakers. "It was extraordinary," recalls a Democrat who attended regularly, "to see ten grown-up couples and then sit next to a fifteen-year-old. Roy was always on the scene. He fit right in." Says Neil Walsh, a boyhood friend: "When he was sixteen, he was forty," Four of his closest childhood friends—Generoso Pope Jr., Si Newhouse Jr., Richard Berlin, and Bill Fugazy—are today, respectively, owner and publisher of the National Enquirer, chairman of the Conde' Nast publications and part owner of the Newhouse communications empire, president of the Hearst Corporation, and owner of one of the world's premier travel and limousine services. For twenty years, Roy exchanged Christmas gifts with FBI director J. Edgar Hoover. Bernard Baruch testified as a character witness at his first trial. Gossip columnists Walter Winchell and Leonard Lyons, who did not speak to each other, showered Roy with praise, as did George Sokolsky.

Hanging out at "21," The Stork Club, and the Latin Quarter, Roy met all kinds of people. In the mid-Fifties. the owner of the Latin Quarter approached him in Miami. "I have a daughter who's a great admirer of yours. She'd like to meet you," the father told him. So, together, they walked over to meet the daughter. "Barbara, I told Roy you were a great admirer of his and wanted to meet him."

"I said I would like to meet him. I didn't say I admired him," Barbara Walters admonished her father.

The conversation went downhill from there. Intrigued, Roy called her the next day for a date. On their first date, not surprisingly, Roy took her to the Bronx County Democratic dinner. Later, on the way home, Barbara broke the news: She was engaged. "So get married," Roy snapped. They did not see each other for three years. Barbara was working with William Satire in public relations for the Tex McCrary agency; Roy was practicing law. But Roy had obviously made an impression. His phone operator announced one morning. "Miss Walters from Tex McCrary is calling." As Roy recalls it, he huffed, "'Well, if Miss Walters from Tex McCrary is calling, let her talk to my secretary.' Two days later I'm playing golf with Si Newhouse, and on the tenth tee, it got to me. I said. 'God. I wonder if that was Barbara Walters?' So I ran off and called her." They started going out. The family thought they would get married, as once they thought he would marry a girl named Joan Glickman. Instead, Barbara became another one of Roy's good friends.

By parlaying his friendships and brains, Roy is today a powerful man. Even when he was considered a pariah, after returning from Washington in the Fifties, he was always seen at the Hampshire House parties of Edwin Weisl, Lyndon Johnson's attorney and a partner in Simpson Thacher & Bartlett; with the Newhouses, the Berlins. the Fugazys, the William F. Buckleys. Through innocence by association, he regained respectability. When Democratic party chief Carmine DeSapio sought the editorial support of the Newhouse newspapers for candidates in Queens or Syracuse, he'd call Roy. As salesmen drop their calling cards, Roy is always volunteering, "Anytime you need help, just call on me." The Catholic Archdiocese, led by his friend Cardinal Spellman, received Roy's free legal counsel, including his help in the school-prayer case.

The Cardinal was given Roy's yacht for a ten-day holiday in St. Thomas and for charitable boat rides. Roy also helped raise money. Every year he would buy a table or tickets to Democratic, Republican, and Conservative party dinners. Though not much of a political giver himself, he raises money through his clients. He serves, for instance, as one of eight on a New York steering committee to collect money for the city-wide Democratic party. At Roy's instigation, the late Lewis Resenstiel, founder and chairman of Schenley and a client, gave $2.5 million to Cardinal Cooke for the Cardinal Spellman Foundation and $1 million to christen the Hoover [J. Edgar] Foundation. Roy knows how to flatter friends. "I was sitting next to Rosenstiel once at the annual Al Smith dinner," recalls a New York pol. "He was just sitting there, looking around. Suddenly he stood up and saluted Roy Cohn, calling him 'field commander.' Roy stopped and saluted Rosenstiel, calling him 'supreme commander.' It was unbelievable."

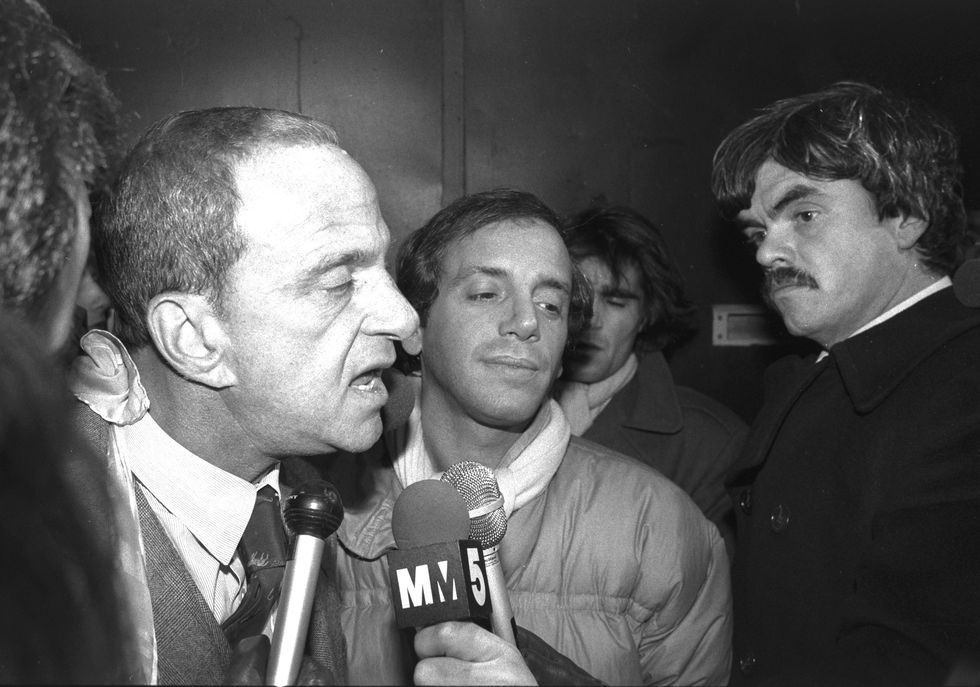

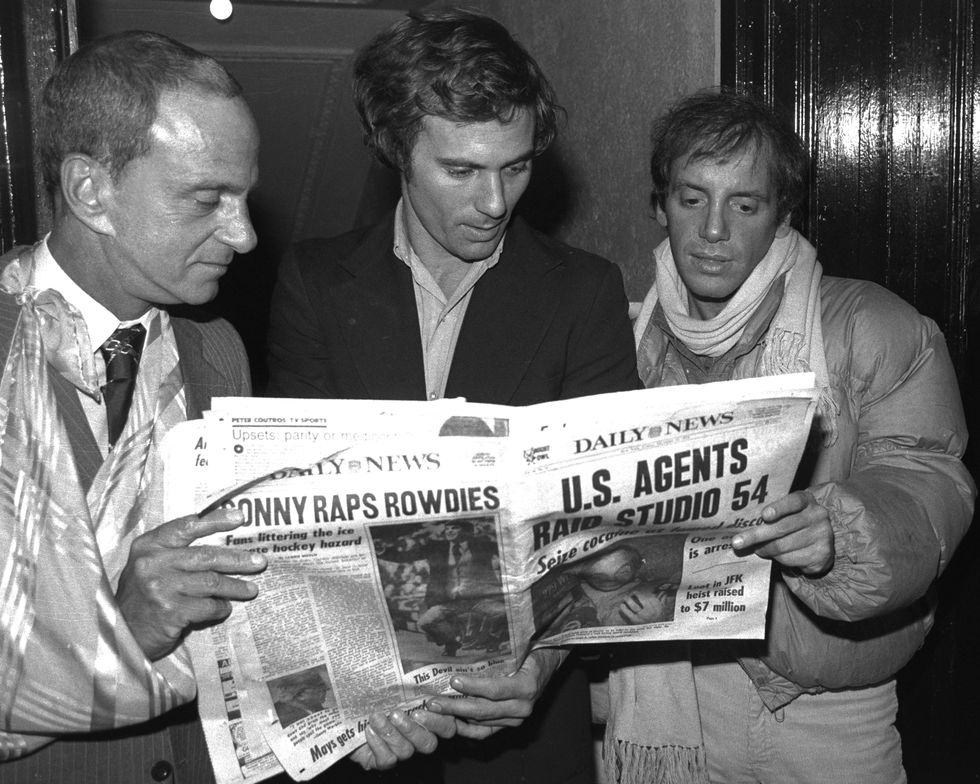

Former Mayor Beame was a friend of Al Cohn's and came to rely on his son for advice. Stanley Friedman, Roy's new law partner, was deputy mayor under Beame and with Roy's prodding sought and won the post of Bronx Democratic chairman. The Brooklyn leader, Meade Esposito, turns to him for free legal advice, sending elected officials threatened with indictment to Roy for help. He represented Manhattan Republican chairman Vincent Albano in a divorce proceeding. When you're in trouble, Roy is a comforting presence. Not only is he supremely confident; he's living proof you can escape just about anything. But don't cross him. State Liquor Authority chairman Michael Roth, leading a posse of policemen, closed the disco Studio 54, a client, one night for operating without a liquor license. Cohn didn't forget. "In the spring of 1978, when the state Conservative party was about to nominate Roth for attorney general. Roy called me and was really irate," says state chairman J. Daniel Mahoney.

The party went ahead and nominated Roth; and Roy went ahead and engineered that party's first statewide primary, supporting David Caplan. Roth, who also had the Republican nomination, was forced to divert an estimated $40,000 and precious time scouring the state to find the 114,000 registered Conservatives. Roth won, narrowly. But he's haunted by the memory of Cohn. "It was like chivalry," he says. "A personal insult must be avenged.

Parties also add to Cohn's power. Given at Studio 54, the East Sixty-eighth Street town house, or his three-and-one-half-acre estate in Greenwich, Connecticut, they attract a chorus line of judges, mayors. elected and party officials, monsignors and priests, publishers, gossip columnists, writers, models, actors, landlords, businessmen, celebrities. "I used to be wary of Roy, but then I went to one of his parties, and the people I saw there were all respectable," says builder and Association for a Better New York chairman Lewis Rudin. "He seems to know every¬body." chimes new friend, New York's deputy mayor Herman Badillo. "A good lawyer," clucks client Sam Lefrak, "must keep a line of communication open to political people. You must have a relationship. You can't just walk in. You got to know the judges. You got to know the clerks. You got to know the procedures."

A KILLER IN COURT

Steve Rubell, co-owner of Studio 54, admits he's gotten some grief because of Roy. He met and was accosted by Lillian Hellman in California: "How can you have Roy Cohn represent you? He ruined people's lives." But Steve, like many of Roy's other friends, dismisses that as ancient history; "Look, I did crazy things when I was fifteen years old." Besides, Hellman has only seen Roy Cohn the monster. His friends see something else. At Roy's spring birthday party, held at comedian Joey Adams's home, Barbara Walters, David Edelstein, chief judge of the U.S. District Court, Baron di Portanova, TV host Stanley Siegel, gossip columnists Earl Wilson and Virginia Graham, and Donald Trump all stood up and toasted Roy. "When you're down and out, you can count on him," was their refrain. Afterward. Roy got to display his gracious side. "I gave him a party at Studio 54," Rubell says. "He invited one hundred fifty people. Three thousand to four thousand showed up. Margaret Trudeau showed up. Everyone! I had a cake made of Roy with a halo around his head. This big cake was on a stand. Then Margaret Trudeau went and sat on it."

On purpose?

"No. Margaret Trudeau doesn't do anything on purpose—even think. But Roy went up to her and said, 'You weren't supposed to do that now. Do it later.' Instead of making her feel like an idiot, he made her feel comfortable. He's very gracious."

Roy was certainly gracious to Charles Allen Jr., chairman of Allen & Company. While Rubell was sprawled on a couch in the middle of Studio 54's dance floor, brooms sweeping clean the confetti and debris from the night before, a messenger appeared with a hand-delivered letter from Roy, tersely commanding "a membership card today (unlaminated OK) for Charles Allen Jr." It seems that Mr. Allen couldn't get into Studio 54 one night and thought to call his wife's divorce attorney for assistance. Roy favors his friends with parties and VIP treatment at Studio 54 and passes to Yankee games. When President Carter's inflation czar, Robert Strauss, the former Democratic national chairman, wanted his wife to see Studio 54, he arranged it through Roy. "Between Studio 54 and the Yankees, I feel like a ticket agent." says Roy, not quite complaining.

Yes, sitting here at his favorite "21" table, Roy has reason to be content, to feel mellow. But he is combative, expounding on some favorite topics: "stuffed shins" and Wall Street law firms. The bar association: "a bunch of unctuous power brokers." Welfare: "No politician has the guts to tackle welfare fraud." Andrew Young: "a racist." In many ways, Roy hasn't changed since the Fifties. He still talks of "the Iron Curtain" and worries that Russia and China will "bury the hatchet because their goal is the same; the Communization of the world," The future: "I believe there's going to be a Communist world someday." Roy swaps confidential tidbits about some of his clients, asking that the reporter keep it off the record, of course. It is titillating stuff to hear of the armistice Roy negotiated between a well-known man and his wife. They now share separate quarters of the same apartment, separate phone numbers, separate lovers, and they never. but never, talk to each other. Presumably, such morsels are the favors Roy bequeaths his gossip-columnist friends.

It is 4:00 P.M. The room is empty, save for the waiters polishing plates for dinner and reassuring Roy that he may stay as long as he wishes. It's time, however, to go to court. But first Sheldon Tannen, an owner of "21" asks if he may please steal a moment of Roy's time to discuss a personal matter.

Outside, a white Chevrolet and driver are waiting—a temporary substitute for Roy's customary black Rolls-Royce—to take him to the state supreme court's appellate division. Al Cohn's picture, like that of other past judges, adorns the wall of the courthouse, and Roy is one proud son: "He had everything I don't have. He could control his temper. He didn't hate people's guts. The funny thing is that his reputation is enhanced because of me."

The courtroom is not unlike a church. Thick stained-glass windows reach to the ceiling, which arches into a dome decorated with the names of former justices, including Al Cohn's, and peaks into a blue-and-green stained-glass centerpiece. Frescoes grace the walls. The five appellate judges sit behind a curved, elevated, and elaborately carved mahogany bench. Kneeling before them is the conference table, divided by a portable lectern, where opposing lawyers sit. Behind them and to either side are wooden benches, arranged like pews, for spectators. There is a flutter among the few spectators as Roy enters. He is a celebrity, a showman, it doesn't matter who his client is—today he is arguing an appeal for Fred Trippe, whom Roy did not represent when he was convicted of falsifying the records of his methadone-testing laboratory and bilking the city of thousands.

A legend has grown up about Roy Cohn's courtroom appearances. Judges and others marvel that he can speak for hours without notes and has total recall, including the ability to recite the page number of testimony given months before. It is said by many that he will lie, cheat, invent facts, smoke with bullying rage, or ooze with charm—whatever is required. Says one of his Columbia law school classmates who loathes hi,. "There is a feeling in the legal profession that he is a formidable adversary not because he's a brilliant lawyer but because he will stop at nothing." Dick Schaap, the WNBC sportscaster, met Cohn for the first time in a divorce proceeding with Schaap's wife, whom Roy is representing. "My wife would point at me and say, 'He's a liberal, Roy. He hates your guts!' " recalls Schaap. Which was true. He remembers walking into Cohn's office and spying a picture of Roy whispering into Senator McCarthy's ear. Schaap fumed. 'Yet he found himself surprised that Roy acted like "a stand-up comic. His timing was perfect. He was charming." What about his reputation as a killer? "It hasn't gotten that far yet," he says. "I may not be laughing long."

"His ability as a public speaker is probably the best in the business." certifies James LaRossa, who enjoys a reputation as one of the best criminal lawyers in the business. But, says a prominent attorney who has worked beside Roy in cases, "1 could make a great trial lawyer out of him. He is spread too thin. He's really not a good trial lawyer because he doesn't have time to do the homework, and it shows in his cross-examination of witnesses." Sometimes it shows in his briefs. In the Henry Ford class action suit, Roy wildly charged that a "Morris" Taubman received inside information about a Detroit land deal from his friend Henry Ford. The man's name is A. Alfred Taubman. The papers also charged that Ford gifted model-agency business to the Leslie Fargo Agency, where Kathleen DuRoss, "a person in a close personal relationship with the defendant. Ford, has an interest." The owner of the agency signed an affidavit swearing that DuRoss has never owned an interest in her business.

Cohn's fabled self-assurance is on display today. Without notes he plucks from his memory the page number of past testimony, marshals his arguments precisely, pausing only to step back, to slide his arms behind his back, and pace before the justices. When Roy is finished. Assistant D.A. Jerrold Tannenbaum, his adversary rises. "Your Honor!" he booms. voice throbbing. "There is no way this court can determine this appeal if the record is falsified." Roy sits motionless, staring straight ahead, arms folded, intently biting his cheek. As soon as his young foe pauses, Roy leaps from his chair. never once taking his eyes from the judges, nudging, almost pushing Tannenbaum from the podium. "I think he owes this court an apology!" he barks. But there is no conviction in Roy's voice. He is used to being attacked. What other lawyers would consider a blight on their integrity, Roy considers perfectly normal. When Henry Ford's attorneys documented in open court the times Ray's ethics have been questioned by judges, Roy shrugged it off. "He actually thinks it's normal to be reprimanded by a judge," says one of Ford's shocked attorneys.

What this attorney doesn't understand is that to Roy the courtroom is not a forum where gentlemanly adversaries gather. It is a battlefield: an arena where his enemies, he believes, try to kill him, The story of his trials, or at least his four New York trials, are recounted in A Fool For a Client, a book Roy wrote in 1971.

CRIMINAL INDICTMENTS

In the United Dye case, in 1964, Cohn was tried by then U.S. attorney. Robert Morgenthau with the support of Attorney General Robert Kennedy. The grand jury indictment charged that Roy sought to obstruct justice in order to prevent the indictment of four men in a stock-swindle scheme and then perjured himself by denying it. Roy retorted that Kennedy and Morgenthau were engaged in a "vendetta"—Kennedy because Roy got the job he wanted as counsel to McCarthy: Morgenthau because he resented Roy's charges that his father, the former Secretary of the Treasury. naively allowed Communists to work in and undermine his agency and the United States. The case ended in a mistrial when one juror's father died. When retried, Roy was acquitted. Cohn's second and third indictments from the Morgenthau office came within two months of each other in 1968 and early 1969. The third indictment was tried first. In the Fifth Avenue Coach Lines case, Roy was charged with bribery, conspiracy, extortion, and blackmail for allegedly bribing a city appraiser to help his client, Fifth Avenue Coach, snare a higher award in a pending condemnation trial. The trial contributed to the Cohn legend when his attorney, Joseph E. Brill, was felled by a heart attack. It tells you something about Roy's Machiavellian reputation that there are those who believe the heart attack was feigned so Roy could offer his own summation. The advantage of defending himself, however, was clear: Since Roy had not been called as a witness in the trial, he was now free to offer his own testimony without being cross-examined. For two days. without a note, Roy delivered an eloquent seven-hour summation, ending with a protestation of love for America. Tears streamed down Roy's and the jurors' cheeks. Then the jury was sequestered to deliberate.

During his first trial, when the jury sent in some questions for the judge, it looked bad for Roy, remembers his friend Neil Walsh, "But Roy insisted we all go to Luchow's for dinner. It was like a funeral. Even Roy's attorney said, 'Roy, you got to admit it looks bad.' But Roy said, - -- -it. We'll win on appeal.' " Now, as the jury gathered and Roy's clse friends huddled and bit their nails, the defendant rushed off to catch the opening-night performance of a new play, The Mundy Scheme, directed by and starring two men who once befriended Roy's beloved mother. Again, Cohn was acquitted.

The third trial came in 1971 and was a spin-off from the Fifth Avenue Coach Lines case. Cohn was accused of bribery, conspiracy, and filing false reports with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). Each of the trials featured former business associates testifying against Cohn in return for guilty pleas and their freedom. Again, Cohn was judged innocent. To this day, a former prosecutor believes he was guilty in each case. But he believes Roy is today almost immune from prosecution, the theory being three strikes and you're out.

Morgenthau and his former assistants tend to be defensive about their prosecution, with reason. Cohn was the victim of some of the same vicious techniques he once employed as a young prosecutor and aide to McCarthy. During the 1964 trial, Cohn's mail and that of his attorney was intercepted, earning Morgenthau a loud and well-deserved rebuke from the American Civil Liberties Union. Stories about Cohn were leaked to the press on the eve of the trials before jurors were selected. According to Irving Younger, former Assistant U.S. Attorney under Morgenthau who penned a confessional for Commentary magazine in 1976, Kennedy and Morgenthau personally assigned him full time to "get" Cohn.

They failed to "get" Cohn but succeeded in granting him an aura of invincibility, respectability, and even sympathy. As Sidney Zion, then a legal affairs reporter for the Times, wrote at the time:

"In liberal salons during the dear old days. the free-association game was a cinch: Say the name Roy Cohn and the response was a chorus of Joe McCarthy-witchhunt-vendetta-trial by headline."In conservative watering places these days, the free-association game is a cinch: Say the name Bob Morgenthau and the response is a chorus of Roy Cohn-witchhunt-vendetta-trial by headline."Thus do the ironies abound as time and positions change, as prosecutors become defendants, friends became informers, and informers become friends.Can it be true that in the final months of the Sixties, Roy M. Cohn is carrying the banner for civil liberties in the Southern District of New York?Is it possible that United Slates attorney Robert M. Morgenthau ... has become Joe McCarthy in order to get Roy Cohn?"

LEGAL SKIRMISHES

But there were other charges and judgments against Cohn, ones where the issue remained his, rather than the prosecutor's, behavior. In the civil case SEC v. Fifth Avenue Coach Lines, Inc. (1968), the court declared, "Cohn benefited from the use of Fifth's money to pay the loans made to him by" other directors and sought to "cover up" the participation of two directors in approving questionable schemes. The court enjoined him from violating the securities laws, a warning rap on the knuckles. Roy appealed the decision and los. Legal standards have changed. "Today, a similar warning," says SEC attorney Ted Sonde. who participated in the original case, "would be grounds for dismissal from the bar in most states." Roy remembers the decision more modestly: "They dismissed every charge against me except one; I had been negligent in failing to submit something for board of directors approval."

In January 1970, Cohn and three other men were criminally indicted by a Chicago grand jury for violating Illinois banking laws. Working through Defiance Industries Incorporated, it was charged they connived secretly to gain control of more than 15 percent of the stock of two Illinois banks. In a related civil suit, Cohn and his codefendants were also accused of using the banks for their own purposes, including the cashing of a $50,000 check by Cohn's law firm against a nonexistent checking account. Those charges, remarkably similar to a suit Roy would later lodge against Henry Ford, declared that Cohn used the banks for his own benefit in "total disregard of the well-being of Guaranty, its minority stockholders and its depositors." The criminal charges were eventually dropped.

In United States v. Johansson (1971), the federal government sought to collect back taxes from the proceeds of the third Floyd Patterson-Ingernar Johansson heavyweight championship fight, which Roy promoted as a one-third owner of Feature Sports Incorporated. The lower court held Cohn responsible for the back taxes. On appeal, the higher court found Cohn and his partner Tom Bolan guilty of ignoring the lower court: We "cannot escape a conclusion that both Bolan and Cohn were directly and personally responsible for causing Feature Sports Incorporated to violate the court's orders."

In another confrontation with Illinois banking laws, this time a civil case, in 1973, Illinois circuit court judge Daniel Covelli ordered Cohn and one of his former partners to pay $1.6 million to Louis E. Corrington, former president of the Mercantile National Bank of Chicago. When Cohn failed to appear in court, the judge ruled he had defaulted and awarded the full claim to Corringtou. "Eventually," Roy says. "the suit was dismissed."

In In re: Emilie of Rosenstiel (1976), Cohn was accused of tricking his eighty-four-year-old client, Lewis Rosenstiel, to change his will when he was dying in a Florida hospital. The will change was significant since it would have made Cohn a trustee and executor of the $75-million estate and would have elevated two of Roy's clients—Rosenstiel's granddaughter, Cathy, and her husband, James Finkelstein (son of Roy's client and friend Jerry)—to become trustees of the estate. Dade County probate judge Frank H. Dowling, in a bristling twelve-page opinion, concluded, "Roy M. Cohn misrepresented to the decedent, Lewis S. Rosenstiel, the nature, content and purpose of the document he offered to Mr. Rosenstiel for execution." Cohn, he found, misled his nearly senile client by professing the document he signed with a shaky hand would save one of his five ex-wives from prison. The court voided the amended will. Roy vowed to appeal.

Cohn blames "the local establishment" for this setback_ He also counterattacks Rosenstiel's tax lawyer, Maurice Greenbaum, who pressed the challenge against Roy. Greenbaum, he claims, sneaked into the hospital room while Rosenstiel "was in a coma and put a pen in his hand and had him sign an X to a piece of paper, which divested him of substantial assets out of his estate" (A purely diversionary tactic," says Greenbaum of Cohn's counterattack.) In other words, if Cohn was guilty, so was Greenbaum. The thrust of Roy's defense was not that his ethics were beyond reproach but that Greenbaum's were no better. It was the same tack he took when criticizing Vice-President Spiro Agnew's 1973 resignation for accepting bribes. "How could one of this decade's shrewdest leaders make a dumb mistake such as you did in quitting and accepting a criminal conviction?" read his open letter to Agnew in The Now York Times. "Alger Hiss and Daniel Ellsberg can still argue their innocence. You no longer can." That Agnew was guilty did not offend Roy. What did was that he admitted it. Despite his threat to appeal the Rosenstiel decision, Roy never did.

In still another clash with the Florida courts, SEC v. Pied Piper Yacht Charters Corp. (1976), Cohn and his law firm were charged with civil contempt for breaching their fiduciary responsibility as agents for a $210,000 escrow fund when they substituted a bond for money in the account. Judge Edmund L. Palmieri said Cohn's denial of knowledge about the terms of the escrow account were "not credible" since he had negotiated the terms himself. The judge denounced Cohn and said he was guilty "of obfuscation by hold assertions of half-truths and untruths" and that he listened to his testimony "with surprise bordering on stupefaction." The case was dismissed—"with prejudice"—when Cohn and his associates replenished the escrow account. Roy says that the judge was prejudiced: "Every time we walk into the courtroom ... I think his blood pressure goes up by about one hundred points." He also claims the SEC had granted written permission for what he did with the escrow account. Actually, attorney Michael Harris, of the SEC's New York office, did initial a letter from Roy. But the court found Harris "did not read the enclosed bond" forwarded by Cohn and "was never advised of the true nature of the bond proposed to be substituted. The Court accepts Harris' testimony that he initialed the letter as a courtesy." Besides, the judge intoned, only the court, not the SEC, was empowered to grant approval.

Roy's Florida battles are mere skirmishes when placed alongside his war with Internal Revenue. "Without question," he admits, "I hold the world's record for having been audited by the IRS." They have been auditing his returns for the last nineteen years and claim, says Roy, that he owes the government $1.4 million in back taxes. "Forget about it," says Cohn."I don't even have a bank account. Everything I get, the IRS grabs." They seized his Keogh retirement plan and even a $60 checking account. The IRS is engaged "in a vendetta," he asserts. Nevertheless, he concedes, 'I paid in the last two years a couple of hundred thousand dollars in back taxes." Actually, he paid almost $300,000.

ACCUSED OF MURDER

The IRS is not the only creditor chasing Roy Cohn. From January 1970 to December 1977, no less than twenty-eight judgments were filed against Roy in Manhattan's state supreme court. In fourteen separate cases, judges ordered him to pay the state of New York a total of $71,392.61. In three separate judgments, he was ordered to pay the city $9,328.10• Dunhill Tailors, oil credit card companies, a locksmith, a mechanic, a photo-offset company, a stationery store and office supply company, temporary office workers, travel agencies, and storage companies have all filed claims against Cohn. In seeking payment, these smaller creditors must retain attorneys or bill collectors. It gets pretty expensive, particularly since Roy relishes a fight. For a relatively small bill, it's often not worth the trouble. Rather than pursue Roy, a Manhattan button store swallowed a $60 bill. Asked about these unpaid bills, Roy says that during his nine-year legal battle in New York, monies and energy were diverted to survival, "and there was a total lack of attention to other things." Again counterpunching, he says he was, "a sitting duck" for predators and was hit "with a bunch of phony judgments." Today, however. "ninety to ninety-five percent of the legitimate obligations are all cleaned up," he says.

And, finally, the father of a dead young man thinks Roy "could have" plotted to murder his son. The charge relates to the mysterious sinking on the night of June 22. 1973, of the ninety-seven-foot Defiance, off the Florida coast. The yacht, once owned by publisher Malcolm Forbes, was leased for years by the Cohn firm from Pied Piper Yacht Charters Corporation. Though chartered and used by others, many considered it Roy's yacht.

Before the boat left the West Palm Beach Marina for New York, a number of suspicious things occurred. The local sheriff and Coast Guard had begun investigating reports that the boat was soon to be scuttled. The captain. claiming the Defiance was unseaworthy, refused to take her helm unless she was repaired. The owners refused, and he resigned. He was replaced by David Vogel, owner of a police record in three states who had served time in the federal prison at Lewisburg. A member of the four-man crew, twenty-one-year-old Charles Martensen confided to his father his foreboding that the boat was unseaworthy and might never make it to New York. Nevertheless, the boat left the marina. That night, a fire broke out, and the Defiance went to rest on the ocean's foor. Captain Vogel and two other members of the crew jumped overboard and survived. Charles Martensen did not. According to Captain Vogel, the last person to see him alive, Charles probably got trapped in the galley while trying to silence the roaring flames.

Charles's father. L.T. Martensen, accepted the sinking as an accident—until Captain Vogel called to offer condolences. In describing the events, Vogel said that Charles and he were in the galley together when they suddenly noticed the engine room's bulkhead glowing a bright red, The senior Martensen, a former Navy man and an engineer by training, thanked the captain for his call and went to bed. At 4:00 a.m., he recalls, "The lights went on. Wait a minute. Bulkheads don't glow red!" Then he began to relive the conversation, convincing himself that Vogel sounded as if he had rehearsed his eyewitness account. Alarmed, Mortensen went to the FBI and spent a good part of the next few years sleuthing the case, writing letters. talking to salvage experts, interviewing the crew. On July 11, 1973, he secretly taped this conversation with crew member Gary Tedder:

Martensen: Do you have any suspicion that the fire was not started accidentally?

Tedder: Yeah, I do. That's why I want to go up and see the FBI.... The FBI asked me if I thought the boat was sabotaged. I think it was.

In a letter to the Justice Department, Martensen wrote, "I am convinced that Vogel murdered Charles Martensen by gunshot prior to the arson of the vessel." He urged them to salvage the boat in order to inspect "the skeletal remains of Charley." Hr said it would cost about $100,000. The FBI did not salvage the boat, but it did conduct an investigation. "I must conclude." Assistant Attorney General Richard L. Thornburgh wrote Martensen on April 5, 1976, "that we have not developed such evidence as would demonstrate criminal activity with respect to either the sinking or the Yacht Defiance or the presumed death of your son, Charles Martensen."

The father, who speaks more softly but is no less tenacious than Cohn, remains unconvinced. On a recent visit to New York from his Michigan home, he calmly said, "1 do think Cohn told them to scuttle the boat, I have no question about that." Did he believe Cohn gave the order to get rid of his suspicious son? "He could have." The motive? The $200,000 insurance policy on the yacht.

"He thinks I murdered his son?" Roy exclaimed when told of Martensen's comments. "Let's look at it this way; A, I didn't own the boat; B, I didn't get the insurance; C, the statement is an outrageous falsehood; Four, how am I going to get angry at a man who lost his son? ... You got to feel terrible about it. I'm certainly not going to get into a name-calling contest or a criminal lawsuit against a father who lost his son. All I can tell you is that I understand his bitter feelings, and if he read someplace that I gave a party on the boat or it was my boat, even though I never met his son, never heard of his son, never hired his son, never saw his son in my entire life, and never had any insurance come to me, directly or indirectly, I'm still not a bit angry at a man who reacts emotionally ... Wow, when you lose a son. I couldn't be sorrier for him and for what happened."

The truth of what happened to the Defiance may or may not be under seventy-five feet of water. Certainly, there is no evidence that I know of to charge Cohn with murder or with ordering the boat scuttled. But what of the $200,000 insurance policy? It was paid to a dummy corporation set up by Pied Piper Yacht Charters, owners of the boat—the same company whose escrow account Roy manipulated. According to court papers, part of the insurance money was dispersed to pay off the yacht's mortgage; another $15,875 went to Cohn's law firm for legal fees; another $7,100 went to the law firm as reimbursement for personal property lost on the boat; and $7,950 was paid to Cohn directly for lost property, Confronted with this information, which contradicted his earlier claims, Roy says simply, "This is possible. I'm not sure whether we were paid by the insurance company or by Pied Piper."

IN THE TOWN HOUSE

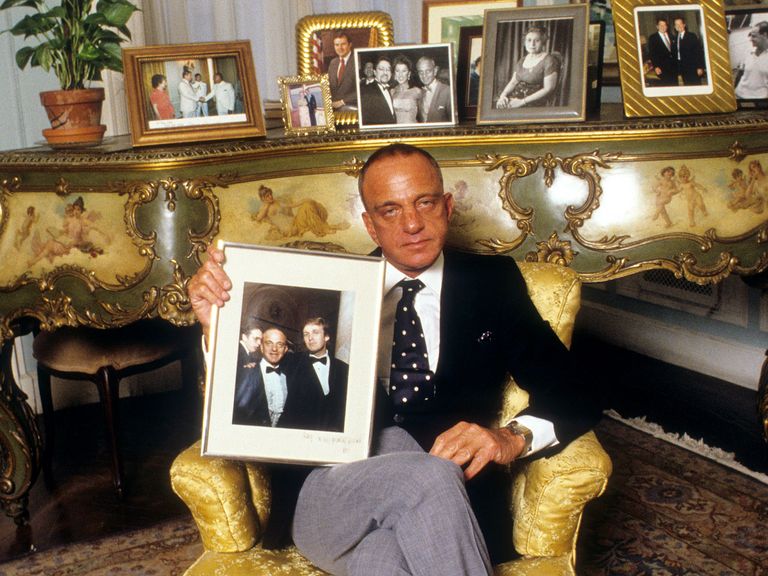

Roy lives comfortably, though one could never tell from his cramped ground floor office at Saxe, Bacon & Bolan, Its walls are littered with autographed pictures, plaques, and press clippings. The gallery includes Roy whispering to McCarthy; Roy with Reggie Jackson—"To Roy. Cosell says you're wearing a piece"; Roy with a halo on the cover of an old Esquire; Roy on the front page of the second section of the Times—"Roy Cohn, at Fifty-one, Enjoys Prosperity and Controversy," reads the headline. J Edgar Hoover, Cardinal Cooke, an American Legion plaque, and a photograph of Al Cohn are among the other items on display. Below the pictures is a small flowered couch. A desk perhaps four feet in length, its surface clean except for two piles of papers, a phone, and three flowers perched in a glass of water, is where Roy works. The desk faces a dark mirrored wall.

Cohn used to occupy the far more spacious office on the town house's 11th floor, the one with a cathedral ceiling, bar, greenhouse, where the secretary works, an outdoor patio and adjoining apartment, complete with kitchen, living room, fireplace, and loft bedroom. But Roy gave the office to Stanley Friedman when he joined the firm in early 1978. Friedman, who sports monogrammed eyeglasses is quite comfortable there. Roy—from all accounts a generous man—is perfectly content in the basement. He spends little time in the office anyway. Meetings with clients are held in the living room on the first floor. The most striking piece of furniture in the room is Dora Cohn's former grand piano, on top of which rest autographed pictures of Ronald Reagan, Cardinal Spellman and Roy together on the Defiance, William F. Buckley, former Senator Everett Dirksen, and Roy's favorite aunt, Libby Marcus. The windows face East Sixty-eighth Street. Adjoining this room is a dark sitting room that opens into a drab olive-green dining room. The table is covered with a cloth and surrounded by four chairs that rest on a stained and wrinkled green-and-blue area rug with dirty white ruffles. A stark, somber Lester Johnson painting looms over the entire room. Not very cheerful, is it? I ask Roy's handsome young administrative aide, Vincent Millard, an aspiring actor. "He's very glum," says Vincent. A swinging door opens to the kitchen. On the next floor, there is a bedroom where Roy sleeps when in town.

After changing from his blue, vested suit, Roy appears wearing a camel's hair sports jacket; bright orange-green-and-blue-striped shirt; fire engine-red knitted tie with matching red woolen socks; and tassled Gucci loafers. His outfit for the Yankees game. But first he must stop and have a drink with Altemur Kilic, Turkey's deputy representative to the United Nations. The Rolls, with cocoa-brown leather seats and the RMC license plate, waits outside the Pen & Pencil restaurant, The ambassador is a large man whose only apparent flair is a goatee and moustache. He is not a smooth man capable of genuine diplomatic charm. Nor is Roy, who is too intense. But Roy is shielded by his celebrity. He orders a glass of champagne on the rocks, a side shot of Stolichnaya vodka, and half a lemon. Popping a tiny white pill from a silver box into his cocktail, Roy commences a monologue for the attentive ambassador about America's "fantastic habit of supporting our enemies and opposing our allies .... The Panama Canal treaty was a sellout and a signal to the rest of the world that we're a bunch of patsies ... When American leaders lose confidence in the country's goodness, forget about it. Here we are screaming about human rights in South Africa--the same week we give the red-carpet treatment to the Soviet Union!" The ambassador says nothing. When Roy finishes and is about to leave, the Turk asks, "Isn't it impossible to get into Studio 54?"

"No, it's easy." Roy says, "You can go anytime you want. We represent them." The bald ambassador, who knew, blurts, "Thank you very much."

"No problem," says Roy, telling the ambassador of the time he was dining at Windows on the World with Barbara Walters and her mother, and the bouncer from Studio 54 tracked him down by phone. "We have a guy here who says he's the president of Cyprus. What should we do?" Roy asked a couple of questions, then said, "Let him in." The Turkish ambassador would never have to suffer that indignity.

JET-SETTING STYLE

As the Rolls aims for Yankee Stadium, in the Bronx, Roy is asked about his friends. "God. I have so many good friends," he answers. "I could name you fifty people." Or more. The first thing many think of when the name Roy Cohn is mentioned is McCarthy, or even evil. But ask that same question of many who know him and they answer friendship or loyalty. Carmine DeSapio may no longer be leader of Tammany Hall or the Democratic party, but he still gets invited to Roy's parties. Monsignor Gustav J. Schultheiss may no longer be secretary to a cardinal, but on his seventieth birthday, recently, Roy surprised hem with a party. When Abe Beame was denied his party's renomination for mayor and left city hall, Roy continued to invite him to parties. "I hated to see Abe Beame at Roy`s last birthday party," remembers Rubell. "'No one was talking to him. Abe was just walking around. Mary Beame was at a table by herself. Well, Roy sat down for one hour at his own party and talked to them. He even took Mary Beanie on a tour of his house. He understood their pain."

With notable exceptions—welfare mothers, for instance—Roy identifies with victims. "You'll talk to dozens of people who were on the balls of their ass and you'll find that Roy took their case gratis," says partner Friedman. "The reason is simple. He has gone through the trials and tribulations of being a victim. He knows what it is to stand alone. When he's a friend, he's a friend for life." His law firm, like his friends and clients, is part of an extended family. Tom Bolan, his partner for twenty years, allows Roy to sign his name to documents and stashes some of Roy's intemperate letters in a drawer "to cool," The firm's president, John Lang, is married to Rita, daughter of Vina Murphy, the Cohn family's former maid. The Cohns helped finance John's law school education, as Roy now provides a paralegal job with the firm for John Jr. Several of the firm's employees have been there for a quarter of a century, and Roy is fiercely loyal to them. "When I had my three trials, they were all there seven days and seven nights a week." he declares.

"To accept a client," says Roy, "I either have to like the client or feel they are getting a rough deal. The same kind of rough deal I got. I have to develop an equation, a community of interest with the client." Steve Rubell is a client Roy likes. "I speak to Roy about every day," Rubell says. "I call him. He calls me and asks, 'Is everything okay?' I think he thinks I'm a vulnerable person. He thinks I'm too soft." Roy's boyhood friends remain his adult friends. He takes pride in his seven godsons, contributing to their trust funds. "It is," says a disparaging former prosecutor, "right out of Grease. Roy never grew up. He has kept his high school friends. When we were young, there was that same intensity of friendships Roy has today."

Like his friends, Roy's weight also remains fixed. He stays a trim 144 pounds by doing 200 daily sit-ups and water-skiing every day but four over the last three months on Long Island Sound. Those little white pills in the silver box arc saccharine tablets. Food is not important, and Roy has been known to forget to order in restaurants, preferring to pick, with his hands, at the plates of friends.

His life-style is not as rooted as his friends or his weight. Roy is always jetting about the world on business. Rarely does he stay in any one place very long. He vacations each year with clients on the island of Mykonos, with the di Portanovas in Acapulco, on British investor Schlesinger's boat in the south of France. Life changed when his mother died. After returning from Washington in the mid-Fifties, he lived at 1165 Park Avenue with his parents. When Al Cohn died in 1959, Roy remained devoted to his mother, sharing the apartment and enjoying the breakfasts she made for him each morning before she died in 1967. "His life-style changed completely when his mother died," thinks Bill Fugazy. "Roy was closest to his mother. She gave stability to his life. There was a lot of entertaining at home. His father and mother were two superb human beings. Now Roy spends time in Europe. He flies over for a day." He relaxes at Studio 54, Yankee games, or luncheons with socialites.

Roy's liberal, jet-setting life-style doesn't square with his conservative politics. It is just one of many contradictions. He hates "stuffed shirts" yet befriends and represents several of that species. He can be a coldhearted executioner—and a warmhearted friend. He blasts "canaries" like Joe Valachi and John Dean who rat on their friends but has no sympathy for Dashiell Hammett, who refused to finger his Communist friends for the House Un-American Activities Committee. His heroes include such conservative icons as J. Edgar Hoover, William F. Buckley, Barry Goldwater, and Douglas MacArthur, yet his friends include such liberals as Paul O'Dwyer, Herman Badillo. and Fred Friendly, producer of the Edward R. Morrow special that did so much to defang Senator McCarthy. He abhors "Nazi-like tactics" of law enforcement officials who prosecuted him, professes support for the American Civil Liberties Union and those defendants' rights promulgated by the Warren Court—yet blindly supports FBI officials who used such tactics and violated those rights. He is a self-proclaimed "cynic" who nevertheless calls many of his cases "causes," He enjoys a near photographic memory yet has a curious propensity to forget important facts.

To discuss some of these contradictions, the afternoon after the Yankees won their game, Roy allows me to join him on the town house's patio. The "lousy weather bureau," as he calls it, had predicted rain, so he canceled water-skiing and a late swim in his heated Greenwich pool. But now the sun is shining, so he removes the camel's hair sports jacket and powder-blue LaCoste shirt, revealing solid arms and shoulders and an even bronze tan, front and back. "'Just wait a second," he asks, grabbing a deck chair and pushing it into a corner facing the sun, spinning the top of a jar of specially prepared suntan cream and rubbing liberal doses on his face, neck, and shoulders.

Just as Roy closes his eyes, the phone rings. "Tell the judge that's fine," he thanks federal judge John Cannella's Law clerk. Roy is seeking to goose along a new trial motion for formercongressman Frank Branca. who served a prison sentence for conspiring to accept payoffs from mobsters and who is a personal favorite of Brooklyn leader Meade Esposito. Roy is shepherding the case as a favor to his friend Meade, as he handled George Steinbrenner's appeal to baseball commissioner Bowie Kuhn when the Yankee owner was suspended because of a conviction. Is it true that the IRS has a lien on all his earnings? "I'm not really clear on that," he surprisingly answers. "I don't think they have a lien on any of my earnings." Handed a twenty-two-page court document—Notice of Tax Lien—from the IRS, itemizing two decades of back taxes owed by Cohn and his firm, he leafs through it and blithely declares, "This is a routine thing. Its no big deal." A big deal, he says, would be if IRS had placed him under "a jeopardy assessment, which means they grab everything you have." Is the reason they do not grab everything because he owns nothing? Not the house in Connecticut or New York, not the shirt off his back or the red-white-and-blue socks with stars he now has on his feet? Is it true that he expenses everything to his firm to avoid the tax collector?

Ridiculous, he responds. His answer is only half true. Roy says his salary ranges between $75,000 and $100,000 annually from the law firm—not a lot for a man who brings in an estimated $1.5 million in legal business each year. "We have an enormous overhead," Roy explains. "And 1 have no need for it." One reason they have a tremendous overhead is Roy's expenses. Besides owning the town house—technically owned by the 39 East Sixty-eighth Street Corporation—the firm pays part of the rent for Roy's Greenwich house, owns the three cars Roy uses—the 1957 Rolls, a deep-green 1952 Bentley with white upholstery and license plate ROY C, a 1978 white Cadillac convertible—and pays for his phones and most of his meals. Were his expenses $100,000 a year? Roy says that's way too low but refuses to provide a figure. A former associate claims they are between $300,000 and $400,000. "My life is ninety-nine percent intertwined with my clients. My social life is intertwined with my clients,'" says Roy. "My life is ninety-nine-percent business." The law firm, incorporated three years ago, also carries more than a $1 million life insurance policy on Roy and has just introduced a profit sharing plan for its members. In addition to his salary and profit sharing, Roy's arrangement with the firm permits him to retain any business "I try outside of New York and Connecticut" and any earnings from writings, including a book on divorce he hopes to finish soon. Business investments, he says, are limited to Florida real estate. As for incidentals: "I pay for my clothes. I pay for food." Isn't it true that by relying so heavily on expenses, he is slipping the IRS? "I don't know. Partly," he admits. Then why is Roy any different from Henry Ford, whom he accuses of using corporate funds for his personal benefit? "The expenses they pay for Henry Ford were his personal expenses," he says. "The only thing the company pays for me is for entertaining and retaining business," And for using the car to take him to Yankee games.

This is not chiseling in Roy's mind. He knows he is not a greedy man. Even as a boy he would plop money on a desk and anyone who wanted it could take it. He forgets to bill clients, is generous io his godchildren and law associates. Unlike many prominent men, he notices and is kind to doormen, chauffeurs, little people. But Roy feels government was and is out to screw him. They persecute him. Cost him a lot of money and heartache. Besides, it is a contest, a battle of wits. Roy pictures himself as the populist, the little guy taking on the establishment. He is incapable of making a connection between what he does and what he accused Henry Ford of because Ford is a big shot, a country club type, a guy born with a silver spoon in his mouth. Even though Roy was born to wealth—the Marcus family owned businesses that evolved into Van Huesen clothes—and benefited from connections, he sees himself as a victim. Even when he was counsel to McCarthy and compelling a fair number of people to cower, including President Eisenhower and the Republican and Democratic party establishments, Roy saw himself and McCarthy as victims. They got him and McCarthy in the Fifties. They tried to get him in the Sixties. And now he is getting back. Justice—western style.

THE CYNICAL VIEW

Roy's concept of loyalty is not unlike that of a mob chieftain. "From the standpoint of my own personal moral code, I can think of no circumstances under which I would testify against a friend," he says, pushing back the chair to stay in the sun, which is sinking behind the roof. "Life is too short."

What if the friend did something wrong?

"What, selling heroin? I wouldn't represent someone who I believe sold heroin. The moral judgment I make is that I will not handle the hard-drug case; except if the person is guilty, I will negotiate the plea whereby the person admits his guilt and goes in and pleads guilty."

Let's say you were Frank Serpico and your buddy on the police force was on the take. The Knapp Commission investigating police corruption asks you about it. What do you say?

"And this was a very good friend of mine?" says Roy. "I'd quit. I'd quit the police force."

But you can't quit the human race. What would you say to the commission?

"I'd do everything I could to avoid—er, I wouldn't lie under any circumstances. But I'd do everything I could, within the bounds of legal propriety, not to hurt someone whose friendship I had accepted."

Even if they had committed a dishonorable act?

"Well, when you get down to the question of a dishonorable act, unless it's something heinous, like the killing of a cop or an innocent person or hard drugs or something like that, I don't consider my-self a one-man ombudsman."

Isn't that a cynical attitude?

"Yes. I'm very cynical, there's no quesrion about it. That's why I was cynical about Watergate. I mean, I've seen this stuff all around in every political situation for years and years. And it's another thing that engendered a degree of sympathy on my part for a guy like Nixon, who was born in a log cabin. Because I know that the alternative political campaign costs enormous amounts of money. Cash contributions exist, I suppose. Always will, I suppose. And when you pillory a guy who never had anything and worked his way up ... you're sort of leaving the world to the Rockefellers and the Kennedys, whose acts of theft are barred by the statute of limitations. So I am a cynic."

But wasn't Nixon deficient in character?

"Not only character but deficient in judgment. I mean, that he kept those tapes, which they didn't have to make in the first place, is a little bit off. What was the deficiency in Nixon's character? You mean the fact that he didn't turn in Mitchell and Haldeman and Ehrlichman? Did President Eisenhower turn in Sherman Adams? Did Lyndon Johnson turn in Bobby Baker? Did Jack Kennedy turn in Judge Morrissey? Yes, I am a cynic.... I think Nixon's deficiencies were magnified out of proportion, particularly by comparison with the up until then accepted norm. Does Carter have deficiencies because he spent three months taking a totally indefensible position in supporting Bert Lance and coming out with nonsensical statements like, 'Everybody in America overdraws,' when you were talking about an overdraft of almost half a million dollars on a noninterest-paying basis—which anybody else would go away for five years if they did something like that? So I just don't see where Nixon's character deficiencies dwarf those of his predecessors or successors.'

Using his feet, Roy jams the chair against the doorway to catch the final moments of the sun's rays. Except for his face, shade blankets his entire body. Conceding that past Presidents employed dirty tricks and, in effect, covered for their friends, as Carter did for Lance, Roy is asked whether the American public doesn't have a right to expect higher ethical standards from its Presidents?

"It apparently doesn't work very well, does it? Because Nixon's successor is Carter. Do you see a real difference between Bert Lance and ... "

But Roy, Carter blindly defended his friend, he didn't engage in a criminal coverup, did he?

" ... It may be a matter of gradation."

It's a grubby world. Roy thinks. With the exception of his extended family of friends and associates, it's all a jungle out there. "The reason I love dogs," he says, "is that you know they're sincere." Roy's life-shaping experiences with the outside world teach that it is composed of hostile forces: the Rosenbergs and other spies when he was a young prosecutor; Communists and dupes when he was with McCarthy; the federal government when he was brought to trial in the Sixties. His life has been consumed by controversy, fights, feuds. The attacks against Roy Cohn by his enemies have sometimes been no less vicious thin his. Therefore: Everyone lies, smears, covers up, protects their friends. The rules of the game don't count as much as winning, which explains the ease Roy has in describing how he would have defended President Nixon:

"Oh, it would have been a cinch," he responds. "Get rid of the tapes. I mean, that takes exactly five minutes. You know, very simple: Did you have a legal requirement to make tapes in the first place? No, it was just my idea, you know, for historical purposes, so on and so forth. So since you weren't required to make them in the first place and there's nothing which requires you to keep them, get rid of them."

How would you answer the charge that you are destroying evidence?

"Because at that point it wasn't evidence. At that point they weren't under subpoena or anything else." Roy gave similar advice to a political client who, he says, "had done something embarrassing and kept a detailed account of it in a diary." Roy told him to "burn it." deep-six it. If the prosecutor asked about the diary? "The answer is yes," he quickly retorted, "But on advice of counsel, I got rid of it. Why'd you get rid of it? Because my counsel said I was under no legal obligation to keep the diary, and that the diary was subject to misinterpretation...."

Does he represent people he knows are guilty?

"Not really. Not really. I think I'd be the worst person in the world to represent somebody I believe was morally guilty. In other words, you can take the Salerno tax case. It was an expenditures case proving, you know, he spent this much money. Here's a fella who was a gambler. I suppose ninety-eight percent of gamblers ... don't file income taxes. Period. Tony Salerno never misfiled an income tax in his life, He paid more taxes than any President of the United States."

Do you believe he paid taxes on all his earnings?

"I don't know. But I'll tell you, frankly, no gambler knows what his exact earnings are. Knowing Tony Salerno, I would think he couldn't. I would think the best he could do is estimate. He's very heavy into sports betting and stuff like that, and I don't think he'd actually know."

But except in Las Vegas, sports betting and bookmaking are illegal.

"He, er, wasn't charged with sports betting."

You just said he was "into sports betting." It's illegal.

"So it's illegal.... You mean it's illegal for me to bet on a game?"

Most gambling in this country is controlled by organized crime. The profits from this business are poured into such activities as drugs, infiltration of legitimate businesses,shylocking.

And Tony Salerno? According to Joseph Veyvoda, chief of Organized Crime Control for the New York City Police Department, Salerno is a kingpin of organized crime: "He goes into more than gambling. He's into loan-sharking and taking over legitimate businesses. He's damn close to the top." Sure, everyone deserves a legal defense, even Tony Salerno. But Roy and our most prominent criminal lawyers, while parroting this truth, choose to ignore another: Their fees are made possible by extortion, drugs, murder.

The sun disappears, and so does Roy. Cooperative, perhaps enjoying the game, he invites me to join him for breakfast the next morning. Every day he is in New York, Cohn holds court in the town house's dining room. Elvira, his cook of fourteen years, prepares the same breakfast every day--a lump of cream cheese or farmers cheese, three strips of bacon, and an iced tea with lemon. Members of the firm appear to review office business with Roy, who is dressed informally. Usually, he dons a bright gold silk robe. On this morning, he is resplendent in a pink cotton shirt open at the neck, chocolate-brown twill slacks, and loafers. A phone with Steinbrenner on the other end, is cradled to his ear. First they discuss a legal matter. Then Ron Guidry. Everyone, including Billy Martin, is second-guessing whether manager Bob Lemon should have altered the pitching rotation to save Guidry for a possible play-off game with Boston. Roy just asks questions.

Young associates trickle in. They do not look like Wall Street lawyers. Their suits tend toward plaids; their shirts, to patterns and darker colors; their ties leap at you. Several speak with the rich accents of New York's streets and wear pinkie rings. Roy is proud that he is the only Ivy League (Columbia) lawyer in the firm. He says he won't hire any, since they "lack common sense, and the "toughness" that comes from kids who struggled and worked their way through school. They pepper Roy with questions about legal maneuvers, drafts of letters to people they are about to sue. He fields them like a shortstop, shooting back answers and flicking his hands up and down as if they were flapping fans attached to his wrists. What should be done, asks one of the attorneys, about producer Jon Peters, who did not give their client, photographer Rebecca Blake, sufficient photo credits in his movie, Eyes of Laura Mors? "What can we do to break his balls?" Roy shoots back.

Don't mess with Roy Cohn.

THE LAWYER

This is quintessential Cohn. Be tough, always attack. Don't apologize, except for what he calls "technical" mistakes—style, not substance. Like his admitted mistake of appearing "arrogant" and "smart-alecky" before the Army-McCarthy hearings in 1954, when questioned about his threat "to wreck the Army" if they did not give favored treatment to his buddy David Schine. Ditto his criticism of Spiro Agnew's resignation. Or Richard Nixon's. Or the questions raised in court about his legal ethics. Or his current defense of J. Wallace LaPrade and FBI officials who broke the law—"Nothing these men did was not well intentioned," he says. The focus is on form, not content.

But is Roy Cohn to different from other lawyers, including those who enjoy wrinkling their noses at him? In one sense he is. Roy is more extreme, less wary of overstepping moral boundaries, crasser, less refined, and more candid. But his cynicism is taught in the most respectable law schools. Lawyers arc supposed to be essentially amoral; advocates, not judges; to represent a client, not the truth; to create a reasonable doubt, even if you have none: to turn a trick for a fee—doing whatever is necessary. short of breaking the law yourself, to protect a client.

That distinguished jurist Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote, "For my own part, I often doubt whether it would not be a gain if every word of moral significance could be banished from the law altogether."

Edward Bennett Williams, whom Roy and others consider the finest trial lawyer in America, seemed to agree in Jimmy Hoffa's 1957 bribery trial. The government had a strong case, and a potent witness, John Cheasty, who testified that Hoffa offered riches if he would join a congressional investigating committee and smuggle him confidential memos. As Hoffa's defense attorney, Williams's task was to undermine Cheasty's credibility. He succeeded in black Washington, D.C.. where eight of the twelve jurors were black, by smearing Cheasty as antiblack, accusing him of trying to bust up the Alabama bus boycott. As Williams knew, even if true, the accusations were irrelevant to the trial. But as he cynically suspected, they would not be deemed irrelevant by the jurors. Nor would the surprise appearance of Joe Louis as a character witness. Hoffa was acquitted. Roy pulled similar tricks with Catholic jurors in his trials, inviting Ned Spellman, nephew of the cardinal, to be a character witness. Every time a lawyer advises his client to preface his testimony with, "To the best of my knowledge" or some other hedge, as likely as not he is being true to Holmes's accepted wisdom.

As Mr. J.P. Morgan once harrumphed, "I do not want a lawyer to tell me what I cannot do. I hire him to tell me how to do what I want to do." In China, no such questions are asked. Disgusted with lawyers who defended dynastic landlords, China has simply banned the domestic practice of law.

Whatever complaints or judgments are registered against Cohn, no bar association has ever banned him. Evil he may be, but as Roy reminds visitors, he is a member in good standing. Like an outlaw, Roy may have some notches in his gun, but no one has dared ask him to leave town.