Apr 2, 2024 12:59 PM

Saxophonist, Sonic Explorer Casey Benjamin Dies at 45

Casey Benjamin, the alto saxophonist, vocalist, keyboardist and producer who stamped his distinctive sounds on the…

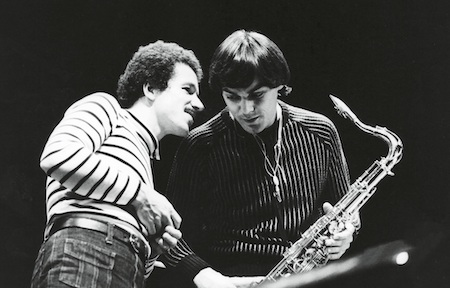

Two ECM reissues of historic albums by saxophonist Jan Garbarek, shown here with pianist Keith Jarrett, celebrate his 50 years on the label.

(Photo: Courtesy ECM Records)

It has become standard practice for jazz labels of any substance and historical depth to revisit, remaster and re-issue gems from their vaults. The natural process becomes ever more significant when the label is one of widely acknowledged and unique artistic importance as well as having attained the elite glow of milestone longevity. Both conditions aptly describe ECM Records. The label that founding producer Manfred Eicher built — and continues building — officially turned 50 in 2019, and its reissuing program of titles from a half century and more ago takes on new cultural meaning with age, and ageless, relevance.

ECM’s latest archival forum comes in the form of two important albums, both from the early 1970s featuring iconic Norwegian tenor saxophonist Jan Garbarek, being issued on vinyl with the original embossed sleeves and fitted with new liner notes. Between the acclaimed and surprisingly sometimes rough-edged Garbarek quartet (guitarist Terje Rypdal, bassist Arild Andersen and drummer Jon Christensen) album debut Afric Pepperbird from 1971 and Keith Jarrett’s Garbarek-featured chamber jazz venture Luminessence, from 1974, the pair of albums nicely demonstrate the range of even the young Garbarek’s musicality. He roamed freely and easily from fervent John Coltrane-esque intensity to clarion lyrical flights suitable for classical-tinged contexts.

By the time of the release of Luminessence, Jarrett’s alliances with both classical composition and orchestration and a kinship with Garbarek were well-established. Garbarek was a key player in Jarrett’s “European Quartet” in the 1970s, along with bassist Palle Danielsson and Christensen (contrasting Jarret’s “American” quartet with tenor saxophonist Dewey Redman, bassist Charlie Haden and drummer Paul Motian). Jarrett had also previously blended jazz and classical machinations on the album In The Light and would continue in 1976 with the renowned Abour Zena, also showcasing the soloing voice of Garbarek, as well as Haden.

(A broad overview of Jarrett’s vast discography reflects his passionate engagement with classical music, both of his own devising and as interpreter of existing repertoire. The newest entry in Jarrett’s discography, for instance, is a luminous recording of keyboard music by C.P.E. Bach, translated from harpsichord to piano and originally recorded in Jarrett’s home “Cavelight” studio in 1994, finally issued in 2023.)

Despite Jarrett’s earlier orchestrated projects in the ’70s, Luminessence — released the same year as the well-known “European Quartet’s” debut Belonging — showed a deeper engagement with Jarrett’s chamber orchestral palette (with the strings from the Südfunk Symphony Orchestra Stuttgart Orchestra). Here, Garbarek was featured as the album’s more prominent and improvisational protagonist atop the string textures. Jarrett’s three pieces on the album form loosely form a suite, evolving from the pensive and lightly dissonant opening “Numinor” through the drone-like brood of “Windsong” and capped off with the joyful pulse and themes of the title piece. Throughout, Garbarek’s signature saxophonic voice soars with a kind of tender heroism.

In his five-star DownBeat review of the album, Ian Carr asserted, “The melodies that Jarrett writes sound like Garbarek improvisations, so great is the rapport between the two men.”

Heard a half century later, Luminessence suggests that it could be an influential seedbed of the impulse for classical-jazz hybridization currently being explored by many musicians seeking to unhinge stubborn genre constraints. By contrast, Garbarek conveys a wilder side of his musical persona on Afric Pepperbird, recorded in the tender early years of ECM’s existence and before any Jarrett link was made manifest. The music contained — and sometimes barely contained — on this quartet debut blends touches of the coloristic and impressionistic qualities to come in his career, but also unleashes an edgy, cathartic intensity evocative of later-period Coltrane’s abandon and the exploratory license of free-jazz and electric Miles Davis voodoo (as on “Blow Away Zone” and the title track).

In a 1971 DownBeat review, Joe Klee lavishly lauded Garbarek’s arrival on the jazz scene, especially in its special case European orbit, noting that his “playing is full of jagged edges and beautiful surprises, Coltrane-influenced but his own. Garbarek should be heard. I would venture that not since Django Reinhardt has there been a European jazz musician so original and forward-looking as this young Norwegian.”

While Garbarek was unavailable for an interview for this article, we checked in with veteran Norwegian bassist Andersen, whose own long and fruitful association with ECM Records as sideman and as leader had its launch on Afric Pepperbird. He would go on to work and record expansively with fellow Norwegians Garbarek, Rypdal and Christensen, but this formative quartet had a particular importance, and expressive firepower. Andersen confirms that the 1970 album “started our early-’70 ties. Manfred and I became good friends and he invited me to several recordings at that time. It has been natural for me to keep the relation with ECM.”

Asked if listening back to the 1970 recording sparked nostalgic or visceral reaction these many years later, Andersen commented, “I think it is just a memory of some starting point for me being part of a quartet — playing freely yet structured and with interplay as a strong guideline, rather than a soloist with a rhythm section. The openness and quartet sound was just in my musical direction and also in the way it was recorded, it made the bass as an equal voice to the sax and guitar. The band was very democratic.”

On Afric Pepperbird, the democratic ideals laid out in top-down fashion from leader Garbarek resulted in opening up select moments to feature each player. Andersen steps forward, as a solo voice, on the tunes “Mah-Jong” and “MYB.” By his recollection, Anderson notes that “‘Mah-Jong’ happened there and then. Jan and Manfred had been downstairs for a cup of coffee and Terje, Jon and I were just jamming when they came back and Manfred said, ‘That sounds great, let’s record it.’ So we improvised a bit and it was included on the record. For ‘MYB’ it came about because I just had practiced harmonics at the end of the fingerboard and this little melody came up. Jan and I did a version of it.”

Touching on more pragmatic memories of the sessions, he recalled, “Most of the music was recorded the second evening. We recorded in the evening when the elevator in the building was less in use — the elevator had to stop when we recorded.”

In terms of musical and attitudinal guideposts for the album’s distinctive mix of muscle, freedom and impressionistic yearning, Andersen pointed out that the bandleader and influential musical theoretician George Russell “was living in Oslo at the time and both Jan and I had been to his lecture ‘The Lydian Chromatic Concept of Tonal Organization.’ We also played in his sextet at the time. The lecture had a great impact on me.”

In its more livewire and raucous passages, the music on Afric Pepperbird runs counter to any stereotyped descriptor of a certain more refined and introspective “ECM sound.” “I don’t think any of us thought about this,” Anderson says on the subject. “First of all, what you could call a stereotyped ECM music had not happened yet,” he says with a soft laugh. “This was just how we played live at that time.”

ECM is a label that prides itself on pristine sonic content and elegant packaging, and has only reluctantly yielded to advancing technological formats, whether the switch from vinyl to CDs in the ’80s or giving in to the digital streaming revolution. With elegantly preserved vintage reissues such as these projects from the Garbarek annals, audiophiles and other purists are invited to savor these landmark albums in the form first presented to the world, in clean, vinyl format.

Count Andersen as one of the true believers in analog technology and other old-school values in recorded music.

“The digital world has made an impact on all record companies,” he admits, but adds, “I like the older version better.” DB

Benjamin possessed a fluid, round sound on the alto saxophone, and he was often most recognizable by the layers of electronic effects that he put onto the instrument.

Apr 2, 2024 12:59 PM

Casey Benjamin, the alto saxophonist, vocalist, keyboardist and producer who stamped his distinctive sounds on the…

Albert “Tootie” Heath (1935–2024) followed in the tradition of drummer Kenny Clarke, his idol.

Apr 5, 2024 10:28 AM

Albert “Tootie” Heath, a drummer of impeccable taste and time who was the youngest of three jazz-legend brothers…

“Both of us are quite grounded in the craft, the tradition and the harmonic sense,” Rosenwinkel said of his experience playing with Allen. “Yet I felt we shared something mystical as well.”

Mar 12, 2024 11:42 AM

“There are a few musicians you hear where, as somebody once said, the molecules in the room change. Geri was one of…

Henry Threadgill performs with Zooid at Big Ears in Knoxville, Tennessee.

Apr 9, 2024 11:30 AM

Big Ears, the annual four-day music celebration that first took place in 2009 in Knoxville, Tennessee, could well be…

“I’m also at a point in my life where I don’t feel like I have anything to prove, like at all,” Akinmusire says about his art.

Mar 26, 2024 12:45 PM

At the risk of oversimplifying and romanticizing the story, Ambrose Akinmusire came bursting on the jazz scene at the…