This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

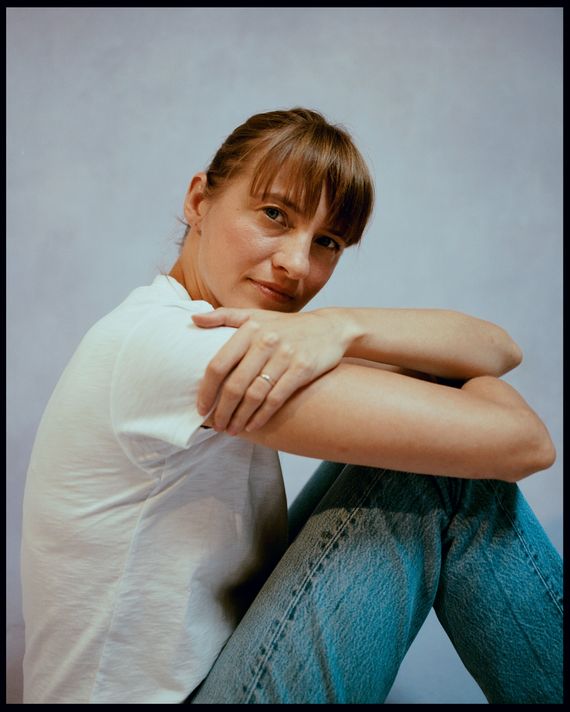

It’s a cold December day and Sara Ziff is sitting in her bright, airy kitchen in Bed-Stuy, sipping chamomile tea. It is perhaps the most relaxed I have ever seen the 41-year-old, an intense and cerebral native New Yorker and advocate for the rights of fashion models — of which she was one for more than a decade. Ziff usually interacts with reporters at rallies and press conferences, where she favors a uniform of a tan suit and low ponytail. But today she is in work-from-home mode, wearing loose-fitting mom jeans and a hoodie bearing the logo for her nonprofit, the Model Alliance. Around her are the colorful giveaways of a toddler in the house: scribbled drawings, scattered toys, a craft table in disarray. On her couch, her rotund rescue dog, Tillie, snores softly. The family has only recently moved here from a smaller apartment a block away, and Ziff tells me they were just able to host Thanksgiving: For the first time since moving in together, she and her husband have a full-size oven.

Despite the casual setting, Ziff is overprepared, pulling up a list of notes as we talk about the Adult Survivors Act — a bill the Model Alliance helped pass in 2022, which opened up a yearlong “look-back window” for sexual-assault survivors to file civil lawsuits outside the statute of limitations. The look-back window has just closed, bringing with it claims against prominent figures like Donald Trump, Eric Adams, Sean “Diddy” Combs, and Russell Brand, as well as a lawsuit from Ziff herself, accusing former Harvey Weinstein associate Fabrizio Lombardo of raping her in 2001. In all, more than 3,000 suits were filed under the act.

When I ask Ziff how it feels to have helped usher in this tidal wave, she pauses, then says, “It does feel affirming.” This is the closest to celebrating Ziff gets. After more than a decade of trying — and often failing — to reform the intractable fashion industry, she’s developed a pessimistic stance on society’s willingness to change. “It shouldn’t be so hard to just win the things that we’ve done so far,” she told me earlier this year, when we talked outside the Greenwich Village apartment where she grew up. “It’s like barely scratching the surface.”

That day in May was a difficult one for her. We had just attended a press conference outside a hearing for E. Jean Carroll’s sexual-abuse suit against Trump — perhaps the most-well-known case filed under the ASA. Ziff and other advocates had gathered to support Carroll and encourage other survivors to file before the November 23 deadline, and Ziff planned to talk about filing her case for the first time publicly. But before she could start, a man ambled by, screaming obscenities about the Me Too movement. Ziff tried to talk over him, but the man was so loud that she could not be heard over his rant. Instead, she stepped back from the podium, silent, and started to cry.

Ziff has a lot to be angry about: that man, her alleged assault, the career she lost and the enemies she gained in her long fight for reform in the fashion industry. For more than a decade, her anger has been her weapon, the driving force behind her relentless activism. But in her kitchen, talking about the ASA, the Me Too movement, and her own case, she displayed something new: an inkling of hope.

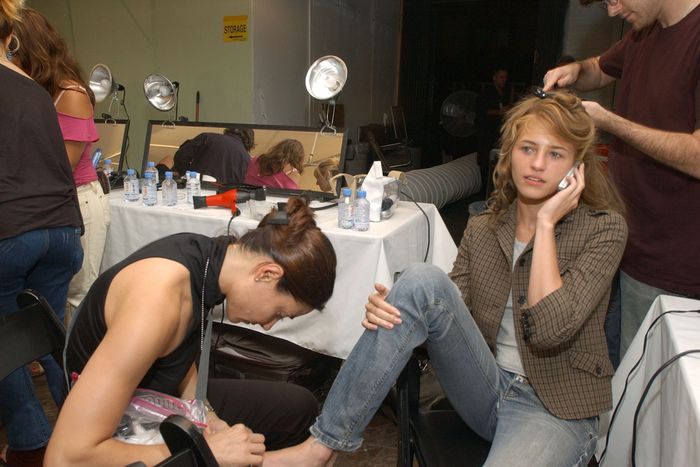

Ziff began modeling at 14, after being scouted on the street by a fashion photographer. “I definitely did not have stage parents,” she told me. Her lawyer mom and NYU professor dad were furious when she told them she wanted to pursue the opportunity. (“I just figured it was better than babysitting,” she jokes now.) She signed with Next Models and started booking serious gigs that same year — Seventeen magazine, the Delia’s catalogue — and decided to take a gap year after high school to model full time. She wound up taking six.

Ziff’s career took off quickly: She booked shoots for Tommy Hilfiger and Kenneth Cole; walked the runway for Prada, Chanel, and Dior; and once appeared on two billboards for two different brands on the same corner in Soho. By 20, she had saved up enough to buy a “sweet loft” in Tribeca. But she was also deeply unhappy. She had virtually no control over her schedule, which was decided, often at the last minute, entirely by her agency. She was frequently paid late or less than she expected and felt pressure to pose nude from a young age. Despite traveling the globe and posing for major magazines, she had never felt more powerless. Looking up at those two billboards in Soho, she’d thought, “If this is what it feels like to be at the top of your game, there must be something wrong with me, because I feel so empty and so depressed.”

Something else happened when Ziff was 19 that made her feel even more helpless. According to her suit, her agency at the time connected her with Lombardo — the former head of Miramax in Italy — in the hopes of landing her some entry-level acting roles. The executive allegedly invited Ziff to a movie screening, then to a hotel, where he said she could meet Weinstein and his brother, Bob. Instead, she claims, he took her to an empty hotel room, forced her onto her back, and raped her. (Lombardo could not be reached for comment.)

Ziff cannot talk about the case in detail because the suit is still pending. But she says she can see the threads of it winding through the next 20-plus years of her life, quietly guiding what she chose to do next and where she wound up today. “Nobody wants to be a victim,” she told me. “It’s just shitty and it’s also something that can take up years of your life — and, like, do you want to dwell on the past or do you wanna just move on?” Still, she added, “Looking back, it’s the elephant in the room.”

Increasingly disillusioned with modeling, Ziff enrolled at Columbia University in 2006 and started taking classes on labor rights and community organizing. “I really was desperate to get out of the industry,” she told me. “I felt like it had already sucked up way too much of my life.” But despite herself, she couldn’t help connecting what she learned to her time as a model. “I remember sitting in class and saying, ‘I know we’re not coal miners, but we’re workers,’ and even being a little embarrassed to say it,” she recalled. “It was just very clear to me that my community, and huge swaths of different worker communities, were cut out of labor law. And I just had a fire in my belly.”

Ziff was still modeling part time, paying her own way through school, and her boyfriend convinced her to start filming her life behind the scenes for a documentary. As she continued her studies and grew more radicalized, the film became less of a voyeuristic ride-along and more of an exposé of the working conditions models endured. When the documentary, Picture Me, debuted during New York Fashion Week in 2010, critics hailed it as an “honest story” about the “ugly side of the modeling biz.” Her agents were less happy. “The film was sort of the first step toward self-annihilation,” Ziff jokes now.

Ziff was also taking classes at Columbia with community organizer Dorian Warren, who introduced her to the idea of workers’ centers — a kind of community group for low-wage workers who aren’t unionized to improve their labor conditions and pay. The idea of organizing models in a workers’ center became Ziff’s senior thesis, then, when it came time to graduate, the basis of her nonprofit. She launched the Model Alliance in 2012, eight months after graduating, with a ritzy, celeb-studded launch at the Standard Hotel. The goal, she said in a statement at the time, was to “give models in the U.S. a voice in their workplace.”

The Alliance earned accolades from major fashion-industry players — designer Nicole Miller and model Coco Rocha praised it to the New York Times — and an invite to the Obama White House. It also helped write and pass a New York law extending child-labor protections to models under age 18. But behind the scenes, the fashion industry bristled. Executives criticized the Alliance’s tactics; agents warned their models not to work with it or risk losing jobs. Ziff herself lost enough work that she had to sell her Tribeca loft and take out loans to get by. When I ask her if she was scared, she responds immediately: “Totally.”

The organization also went through some internal growing pains. In 2014, for reasons no one I spoke with would explain to me on the record, three people on the Alliance’s board of directors abruptly quit. “I had to make some tough decisions,” Ziff told me. With no staff and too little funding to pay herself a salary, she enrolled in a master’s program in public administration at the Harvard Kennedy School, hoping to learn how to continue her work “in a sustainable way.” By the time she graduated in 2016, she was considering winding down the Model Alliance altogether.

Then the Harvey Weinstein story broke. Suddenly, Ziff was invited to speak at conferences and reporters wanted to hear the stories she’d been desperately trying to share. A support line the Alliance had set up years earlier to help models having workplace issues was flooded with calls from models saying they had experienced similar abuse. “I remember answering calls in the early hours — one, two in the morning,” she said. “It was just like the floodgates had opened.” Ziff jumped back into the work full time, helping survivors file police reports, connecting them with attorneys and reporters, and “eating Cheerios for every meal,” she recalls. Although she was exhausted, it felt like she was finally breaking through. “I think it was the first time that anyone really took the work seriously,” she said.

The Me Too movement brought out Ziff’s greatest strength and weakness: her stubbornness. In 2018, the Alliance launched the RESPECT Program—an initiative meant to curb sexual abuse in the fashion industry. The program demanded agencies and fashion brands create a formal sexual-harassment-reporting system and submit to outside investigations of every complaint. The Alliance issued scathing open letters to convince companies to sign on and hosted protests outside the Victoria’s Secret flagship store. Ziff also met privately with leaders from Victoria’s Secret, Condé Nast, and Elite Models about adopting the program. Once, on the eve of releasing an open letter signed by more than 100 models, Ziff says a representative from L Brands, Victoria’s Secret’s former parent company, called her and begged her not to publish it. She declined. (“Our procedures are continuously revisited and updated and reflect elements of the RESPECT Program and beyond,” a spokesperson for Victoria’s Secret said. “We’re proud of this work and remain committed to continuous improvement.”)

In 2021, the CFDA gave Ziff its inaugural Positive Social Influence Award to celebrate her work on sexual abuse. Ziff spent the bulk of her acceptance speech calling out Elite — a major modeling agency under fire for allegations against a former executive — for refusing to sign onto RESPECT. Steven Kolb, CEO of the CFDA, found the speech stirring. “I think she saw it as an opportunity to step into the Establishment and raise her voice, and she did,” he told me. Others felt differently. “People were very upset that Sara got up at the awards and demanded Elite join the RESPECT Program,” one attendee told me. “It was probably not the time or the place.”

This is a common gripe with Ziff: She is fearless and committed but uncompromising. A former employee of Condé Nast told me the publisher seriously considered working with RESPECT but that conversations stalled — and ultimately ended — because the Alliance offered no room for negotiation. “I think Sara had so much conviction in the program she envisioned that it made it hard to work with others,” this person told me. Models, too, told me they were nervous about working with the Alliance because of its aggressive stance. “A lot of us who were still modeling were like, ‘I don’t want to hate on my agent, I don’t want to hate on my agency — they’re freaking paying my rent,” a former leadership-council member told me. This person told me she left the organization because she didn’t feel like it was gaining traction with enough working models.

Ziff told me she understands the impulse to be conciliatory but that she finds it ineffective. “You want to work cooperatively, and you don’t want to seem oppositional, and you want to believe that if only people understood the problem, of course they would want to fix it,” she told me. “But that’s not how companies work. It’s incredibly naïve to think that that’s how you make change.” In a follow-up phone call, she expanded on her hard-line stance: “There’s no meeting in the middle when they’re fighting against their models having even the most basic rights and protections.”

In late 2019, Ziff met a group of advocates who shared her belief in confrontation. The Alliance’s public-affairs consultant introduced her to a coalition advocating for the Adult Survivors Act — a bill that, at the time, was seen as a long-shot. Ziff thought about the dozens of survivors who had called the hotline about assaults that occurred outside the statute of limitations and about how she’d had nowhere to send them. “I was very aware that this was something that would serve our community,” she told me. Ziff, pregnant with her daughter, started driving up to Albany with other advocates to lobby lawmakers and speaking at press conferences with other models. Once, after her daughter was born, she brought the infant to watch a press conference at the capitol. Her husband, a professional photographer, took photos. Alison Turkos, an activist who worked on the bill, told me that Ziff or Sydney Giordano, the Alliance’s only other employee, attended “truly every single coalition meeting.” Turkos added, “The ASA was transformed by her, and she was transformative in the passing of it.”

Where Ziff had felt ostracized by the fashion industry and many of her peers for her work with the Alliance, with the ASA, she felt for the first time like she had an army on her side. “Running the Model Alliance amongst so many people who are scared and didn’t want to stick their necks out was pretty demoralizing,” she told me. “It is pretty demoralizing.” With the ASA coalition, she said, “there was a real sense of determination and mutual recognition … There was a sense of sadness and trauma, but there wasn’t the same sense of fear.”

Which is not to say the work was easy. Lawmakers were clearly uncomfortable with the idea of survivors being able to pursue justice decades later. Ziff recalled attending a vote on the bill in Albany and overhearing two older, white male legislators discussing it. “They were saying, ‘Well, if this passes, how far will things go? What about people who were injured in a car accident? Should there be no statute of limitations?’” she said. “And I was like, ‘Well, there’s no stigma to getting hit by a car, dude.’”

Ziff insists that she rarely thought about how the bill might impact her personally. She was more focused on preventing abuse than seeking justice— so much so, she admits, that she sometimes tried to work references to the RESPECT Program into her ASA speeches. “Before I got involved with the ASA I was singularly focused on prevention — so much so that I think it didn’t even really occur to me until so much later to pursue my own case,” she told me. “I was thinking about everything systemically.”

It wasn’t until the day of the bill signing, a celebratory event at the capitol in May 2022 that she attended with her fellow advocates, that Ziff seriously considered pursuing her own case. Everyone was talking about how to get survivors to file cases during the look-back window, and all of a sudden, Ziff says, “it felt really real — like, this was not just a pie in the sky idea.” The victory gave her the brief reprieve she needed to step back from the work and consider herself. “I realized that I’d been talking about the community’s needs, but I wasn’t really grappling with my own needs,” she told me. “And that’s when it occurred to me to explore my options.”

Ziff filed her case against Lombardo in New York State Supreme Court on April 6 — an event significant enough to earn its own article in the Times. The case is still pending, and the companies that Ziff is suing for negligence — Disney Enterprises, the Walt Disney Company, Miramax, and Buena Vista — recently petitioned to have it dismissed. If the parties don’t settle and the judge allows the case to continue, it will move to discovery and then to trial. It’s a process that could take years and already has taken a toll on Ziff. It unnerves her that an article about rape is the first thing anyone, including the parents she sees at preschool drop-off, will see when they look her up online. “I don’t want everyone who I encounter to know about this fucking awful event,” she said. “For the rest of my life, this will define me whether I like it or not.” She paused, then added, “The process — I wouldn’t try to equate it as being just as bad as the event, but it doesn’t make it better.”

But working on the ASA has had undeniably positive impacts on her work. Days before I visited her home, the Alliance received its first three-year grant — something Ziff thinks was aided by the success of the ASA. Her trips to Albany also connected her to the bill’s sponsor, State Senator Brad Hoylman-Sigal, with whom she drafted a piece of legislation called the Fashion Workers Act. The bill, which would impose basic regulations on modeling agencies, has become the Alliance’s raison d’être — a way, Ziff believes, to force the industry into offering models some rights. The bill passed the New York State Senate this spring but has yet to pass the Assembly, and the Alliance is gearing up for another round of lobbying next year, aided by the same lobbyist who led the fight for the ASA.

Ziff believes the ASA was not perfect and that there is more work to be done to prevent future abuses. She is working with the bill’s sponsors and other advocates on more permanent solutions, like eliminating the statutes of limitations for civil child-sex-abuse cases and extending it for sex-trafficking cases. She also told me she knew several survivors that worked on the bill who never filed a civil case because their alleged abusers had little money to sue for. “It has been really important both personally and for the organization and for beyond our industry, but it hasn’t actually helped everyone who I thought it might,” she said.

But sitting in her kitchen, talking about the legacy of the act, the survivors it helped, and the impact it had on her personally, Ziff started to cry. “Before you came over I was like, “I am not crying,” she said with a smile, harking back to the ill-fated press conference in May. This time, though, she was crying happy tears. “There’s the overused MLK saying about the moral arc of the universe,” she told me, referring to the famous quote about the arc being long but bending toward justice. “I feel like I can see the arc now. It feels like it’s taking shape.” She brightened a little. “Maybe that’s some sort of a silver lining, being able to see the progress,” she said, though she couldn’t help adding, “but it shouldn’t take this long.”