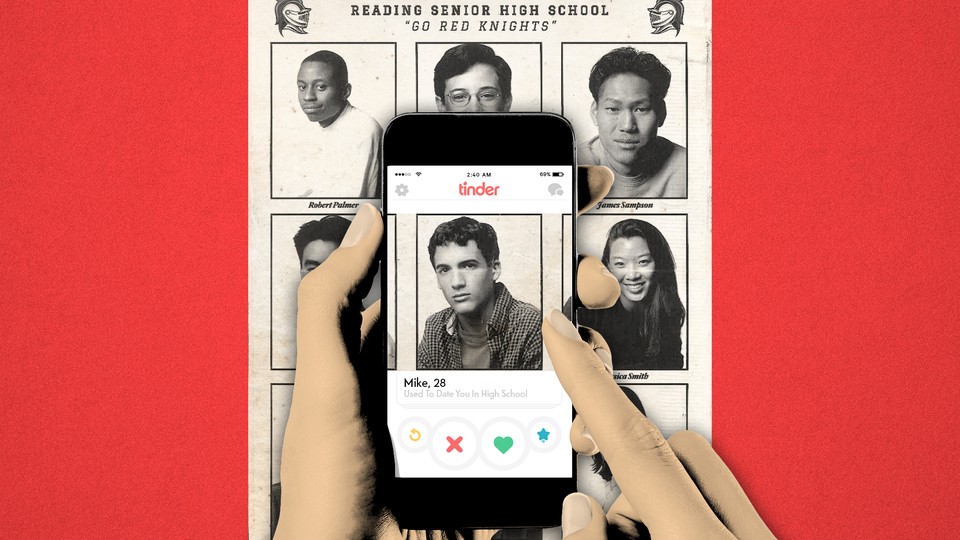

Using Tinder in Your Hometown Is Like Visiting an Alternate Reality

Surfing the app on a trip back home can be a way of regressing, or imagining what life would be like if you never left.

My parents moved out of my hometown almost as soon as I left for college, and therefore I am obsessed with the idea of other people’s hometowns. Over any major holiday or break from a work schedule, hometowns become a sort of time travel, a way for people who have made adult lives elsewhere to return to their origin story.

Going home for the holidays can act as a kind of regression. Most of us know people, whether our friends, our partner, even our own parents, who suddenly turn into their teen or pre-teen self once they step foot in the house where they grew up. My mom used to say that whenever my dad got within 50 miles of his mom’s house, he suddenly became a teenage boy. Our hometowns become a kind of permission and hideaway, a place where we don’t have to be ourselves, where our actions don’t count and we get to be briefly less visible than we are in the adult homes we’ve made for ourselves elsewhere, the places where we expect ourselves to take action and achieve things and move upward through each day. For many of us, hometowns allow the luxury of a brief period of stasis, a rare few days of doing nothing.

Of course, hometown visits can also be boring. Talking about the holidays with my friends after they’d returned from visiting family all around the U.S., boredom was as much a theme as regression. After a few days rooting through high school yearbooks and catching up with parents or siblings, people may start looking for other entertainment. I at least find that when I’m visiting my family, I turn to my phone for distraction even more often than usual. If other people do the same over the holidays, they may end up opening up dating apps. But apps like Tinder are far more novel in a place that isn’t where one actually lives, and they can end up being more than merely distracting, offering insights into one’s hometown, and a way to either regress back to a former self, or explore an alternate one.

I met my fiancé in 2013 (on the internet, but through Twitter, which is technically not a dating app), just before Tinder really took off. I have therefore only ever briefly used it myself, although I am always an overenthusiastic backseat driver on my friend’s Tinder (and Bumble and Hinge and OkCupid) expeditions when they include me. But I did once date my high school boyfriend again after reconnecting in adulthood (it went very badly), and so I understand the potential appeal of hometown Tinder. To this end, I asked some friends about whether they used dating apps while they were home over the recent holidays, what drew them to it, and how the experience differed from using the app where they normally live.

“You kind of use it just to see what will happen,” said a friend, a 31-year-old straight woman who is currently finishing up her residency in internal medicine in a large coastal city, but who grew up just outside Reading, Pennsylvania. “You know it can’t be anything serious, because you’re going home in a few days, so if you open up the app, it’s more as a game than anything else.” Hometown Tinder, as this friend rightly points put, has much lower stakes because you’re leaving soon anyway. One aspect of the app that’s either a feature or a bug depending on your personal preference, is that it turns people into a computer game, rendering living feeling humans into collectibles, like a grown-up version of Pokémon. Hometown Tinder works in somewhat the same way that Tinder works for people who use it while traveling for work—the people are available only temporarily, so it feels less like there are real people behind the avatars.

In one way, the temporariness is what’s fun about a hometown hookup if it happens. Tinder has in recent years become less of a hookup app and more of a dating-focused one, with many people seeking long term serious relationships on it. (Which is not to say that there aren’t still plenty of “U up?” messages and unsolicited penises.) But hometown Tinder returns the app to its origin story. A hookup with somebody in your hometown is likely to be just that, a hookup. One friend, a 27-year-old straight man working in finance who is from a town in upstate New York, pointed out that things are more relaxed on the app over the holidays. “Nobody thinks that anything is something other than what it is, and nobody worries that the other person doesn’t know what’s going on here—it’s definitely not going to turn into a relationship when we’re both going home in a few days.”

But this approach, of course, leaves out the uglier side of using Tinder while visiting one’s hometown. Because people aren’t Pokémon, of course, wherever you are, however briefly you’re there. People like the man quoted above fail to take into account that using the app as a novelty during a visit somewhere can be at the very least aggravating to the people who actually live there. “Oh God, I never open Tinder over the holidays,” says one friend, a 31-year old straight woman working in education who lives outside Minneapolis. “The results are so inaccurate and almost no one ever wants to meet up, and it’s impossible to tell from their location who actually lives here. Figuring out if they’re going to be gone in two days is way too much work and not worth it.” Another friend, a 30-year old straight man who lives outside of Atlanta says, “It would great to meet more people than the ones who are usually on Tinder, because it’s the same people over and over again, but during the holidays looking at it is just a lot of false hope.”

For the visitors, going home for the holidays and hooking up with someone you used to know can be another way of slipping back into your old life, or briefly testing out an alternate life where you stayed in your hometown. Many of us are drawn to the Sliding Doors fantasy of finding out what our life might have looked like if we’d made just a few different key choices. But in reality, this is something many people I know would rather avoid than seek out. “I would never open any dating app while home,” said a friend, a 26-year old straight woman who works in tech and who goes home to Boise, Idaho for the holidays. “Like, what if my high school English teacher who has three kids shows up for me to swipe on? I come from a relatively small town; a lot of people stay here after high school. I don’t want to risk seeing someone I know.”

“It’s funny, because these are all the same people from my hometown I see on Facebook,” says another friend, a 28-year old bisexual woman working in the restaurant industry, who is from a town in the San Francisco Bay Area, near where I also grew up. “But when one of them pops up on Tinder, it’s like I’m seeing their secret lives.” The nostalgia of being back home often brings up the desire to see if friends have changed, to check on the people you’ve mostly lost touch with, and see who they have become. Tinder can be a way of finding out how the people you grew up with are really doing. “Honestly, that’s way more the point of it for me than actually meeting up or hooking up with anybody” says this same friend. “It’s a good way to spy on people.”

While Tinder can be a fun holiday distraction for some, the majority of people I talked to have found it to be a fruitless pursuit, or something better ignored until they return home. “Sometimes I might look at it when I’m bored, but you really don’t expect to actually meet or even message with anybody on there,” says a 33-year old friend, a straight woman working in public health in New York, who is from outside Kansas City. She pointed out that in many smaller towns and rural areas, these apps are virtually non-existent (the dating pool being too small for them to be very useful) and still regarded very differently than they are in big cities. “In New York we think it’s weird when a couple didn’t meet on the internet, but where I’m from, that’s still something you wouldn’t want to admit out loud, definitely not to anyone over 25,” she explains. It’s easy to forget that internet dating is still considered taboo in some places.

And for some LGBTQ people, visiting their hometown might mean returning to an environment where they may not have felt safe and accepted growing up. “I didn’t want to date these people when I lived here, and I definitely don’t want to now,” said another friend, a 29-year old gay man from Wisconsin currently living in New York. “All of that stays firmly shut down in my phone when I visit my family. I don’t even check my messages. I just kind of shut down that part of my life until I go back to New York.”

I didn’t go home over the holidays or, rather, I stayed at home here in New York City, a city that prides itself on being no one’s hometown but is, in fact, just as much a hometown as anywhere else. Over the holidays, New York suddenly transforms from a place full of transplants who moved here to get away from somewhere, to a place full of people who transplanted to somewhere else, returning briefly home.

There are also, it has to be said, suddenly a lot of extremely young people on Tinder during the holidays in New York. “The results get totally weird,” says a friend, a 24-year-old gay man working in media, who often stays in New York over the holidays. “You’ve suddenly got all these kids who are home from college or maybe even boarding school just for the weekend, from, like, Upper East Side families and stuff. It’s a totally different crowd on there.” He admitted that in some ways it was even easier to find a casual hookup because “people are just looking to get away from their families, and they’re happy to travel to you.”

After the holidays, back home on familiar dating turf, a number of friends reported a similar phenomenon: There was an echo left from where they’d been, an apparent glitch in the app, in which faces from miles away, profiles with locations in the same hometown they’d just left, would appear even after they were no longer swiping from there. Tinder did not return a request for comment when I sent an inquiry asking about this occurrence, but more than one person said they thought perhaps this happened because people in their hometown had swiped on them in the time between when they’d last looked at the app and when they’d returned from their visit back home.

These echoes only persisted for a few people I talked to, and only for a few days in each of their cases, but they seemed to speak to something about the way we connect with, and disconnect from, the places we visit. Reminders of the people we could have known, and the alternate lives we could have had, return with us and stay as echoes even when we get back home, carrying around in our buzzing phones the possibilities of an alternate life elsewhere.