It was the moment we were waiting for and the moment we dreaded.

Stephanie Lee had been hospitalized since the day before Christmas Eve 2014, at Mount Sinai, in New York. She had a room on the palliative-care floor. The doctors who cared for her were at pains to say that they could make her more comfortable but that they could not treat her cancer. She was taking massive doses of powerful pain medications. She was eating much less and sleeping much more. When a doctor described his hopes for her in terms not of getting better but simply of getting home to Mississippi, she was at peace both with what he said and what he didn't say.

Then, not quite a week after she was admitted, everything changed. On December 29, a scientist and the oncologist who worked with him walked into her room and announced that they might have something for her. The scientist had been working a year and a half to devise a treatment for her and for her alone—a personalized treatment for Stephanie Lee—and now, finally, his lab had seen what he called "a hit." It was an interesting hit, it was a promising hit, and he came to her room with the oncologist not only to tell her about it but also to see if she remained healthy enough, alive enough, to endure the treatment it entailed.

She was alive enough. Since her hospitalization, she had gone long stretches without speaking, long stretches when she stirred only to press a pump and give herself the medication that caused her eyes to roll back in her head. But she never lost the awareness that she had honed over a lifetime—her daunting gift for seeing people and situations plain—nor the voice that always said the right thing, the true thing, the honest thing, the thing that cut to the bone. Now she heard the scientist and the oncologist out, and, with her eyes closed and her face turned to heaven, she spoke as if from the deepest well of exhaustion and relief and said, simply, "At last."

It was a development that, encountered in a work of fiction, would have stretched credulity. Without prelude, a deus ex machina had arrived upon the scene, and the race against time had begun. As it happened, the scientist needed exactly what Stephanie had left. He needed three weeks, and so what ensued was nothing less than a trial by last hope, with every day bringing the treatment closer to fruition and Stephanie closer to the end. The cancer began helping itself to the few calories she was able to stomach, and then to everything she had. She was always so dignified in her bearing, so erect in her carriage, so put together in every way; now she lay askew in her hospital bed, with the brightly colored head scarf she habitually wore toppled sideways, as if she'd gone on a bender. She could not sit up; she could not lie down; her body had accommodated her pain by settling into a permanent curve. She was a small woman of formidable presence, but the cancer had started distorting her, whittling her wrists down to filaments and inflating her legs into monumental things so swelled by fluid that they had to be moved by attendants. She suffered setback after setback and infection after infection, and yet she hung on for four more weeks in the hospital, far too sick to be discharged, until another oncologist who worked with the scientist walked into her room and told her that the treatment was ready, if she wanted it.

If she wanted it? It was all that she had wanted for so long. And now she had only to say yes, she had only to reach for it. . . .

And that was when she began to die.

She had contracted the gastrointestinal infection C. difficile early in her hospital stay. It had been treated with antibiotics and had receded; but then, as she got weaker, it came roaring back, with the advantage of being the only bacteria left in her gut. She became incontinent, and, as luck would have it, the side effect associated with the first phase of the treatment devised for her, a drug called trametinib, was incontinence. It could make her condition even worse; it could even kill her. The treatment was ready, if she wanted it . . . and if she regained control of her bowels.

It seemed an impossibility, akin to asking a person experiencing an asthma attack to breathe normally as a condition of getting an inhaler. But then a Sinai gastroenterologist introduced himself to her, as well as his specialty: fecal transplants. His name was Ari Grinspan, and he proposed delivering healthy excrement to her GI tract, thereby seeding it with flora that could fight the C. difficile infection. It was a procedure that had a dramatic success rate. The problem was in the delivery. Dr. Grinspan preferred to do fecal transplants by way of a colonoscopy, but Stephanie's colon was comprehensively blocked. That left the introduction of a nasogastric tube, which he would feed into her nostrils, snake down her esophagus, and . . . would we step outside?

We followed him out into the hall, my colleague Mark Warren and I. We took off the gowns, masks, and gloves we had to wear in her room. We listened to Dr. Grinspan detail the risks and benefits of such a procedure—the possibility of aspiration and the certainty of pain—and then ask us if we wanted him to proceed.

For an instant, I thought that he had to be talking to someone standing behind us, maybe someone with medical qualifications. But no—there was no one else. He was talking to us. We had met Stephanie as journalists, then had become her friends and advocates when she got sick. We had introduced her to scientists and doctors at Sinai and had written about Sinai's effort to make her a test case for the potential of what has come to be called personalized medicine. We had tried to do nothing less than save her life and now stood face-to-face with the responsibility required of us. The only way Stephanie Lee could get the treatment we had once written about was if we, as her health-care proxies, consented for Dr. Grinspan to push the tube up her nose and induce her to swallow it down her throat. He described himself as an aggressive doctor, a doctor who likes to err on the side of treatment. But Stephanie was so very, very sick: too sick and fogged by drugs either to give or to refuse her informed consent.

The decision was ours.

***

This is a story about decisions and their consequences. It is a story about hope and its consequences. It is a story about promises, scientific and otherwise, and about journalism and its limits. But mostly it's a love story.

Ten years ago, Mark Warren and I went down to Mississippi to write a story about the doubly devastated—about families dealing simultaneously with the depredations of the war in Iraq and the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina—and met Stephanie Lee. She was twenty-eight years old. She had lost her husband, Terrance, to an IED outside Baghdad shortly before our visit, when she was seven months pregnant. She had given birth to her daughter Marchelle three days after Katrina swept through the Gulf Coast, and the measures she had taken to make sure Marchelle was born in safety and security formed the basis of our story. She was small, strong, smart, proud, fierce, forthright, direct, and utterly clear-eyed about herself and her situation. What I remember most was the conclusion that Mark and I drew after meeting her—that she and her daughters, Kamri and Marchelle, were going to survive, were going to be fine.

Two years ago, Stephanie wrote to Mark on Facebook. Now thirty-six, she had colon cancer. A few weeks later, she wrote him again with the news that the cancer had spread to her liver—and that her oncologist estimated she had up to twenty-eight months to live if she tolerated chemotherapy and six months if she didn't. She asked Mark only to pray for her.

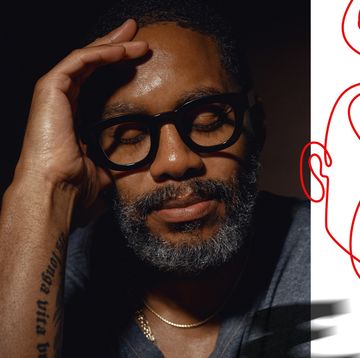

I remember when Mark told me about Stephanie because I was on my way to see another person I had previously written about. His name was Eric Schadt, and he was an evangelical Christian turned mathematician turned biologist turned genomicist who had become one of the evangelical forces behind the "Big Data" revolution. When I first met him, he was working at a small company in Menlo Park, California, and trying to leverage both his Silicon Valley connections and the exponential increase in computing power accessible from cloud services to change the way health care is practiced in this country. Now he had come to Mount Sinai's medical school in New York to open a lab dedicated to using genomic sequencing to invent new treatments for diseases that had proven resistant to conventional therapy, particularly cancer. I had been planning to talk to Eric for a story I was writing about Google. Instead, I told him about Stephanie Lee, and he said immediately, "That's exactly the kind of patient we take."

That's how the story began. But it's not how it ended. Mark began talking to Stephanie, as friend and confidant. He talked to her nearly every day, and shortly after Eric Schadt promised to do what he could for her—shortly after it became clear that Stephanie Lee was going to go from being cancer patient to experimental subject—she asked Mark, "Will you take this walk with me?"

Mark and I had a lot of ambitions for the story of Stephanie Lee, not all of them journalistic. We wanted to live it rather than simply write it. We wanted to connect the disparate worlds of Eric Schadt and Stephanie Lee—of New York and Mississippi—for the benefit of both of them. We wanted to give Stephanie access to the cutting-edge medicine generally available only to rich people. We wanted to see what happened when a powerful medical institution like Mount Sinai devoted the full weight of its financial and intellectual resources to saving one patient, even one with an incurable form of cancer. And all those things happened, pretty much. But only Mark and Stephanie took the walk all the way to the end.

A lot of people try to help Stephanie in this story. A few even try to be heroes. But they are all human, and so they do only what they can. It is left to Mark and Stephanie to give everything they have.

***

People always ask what was different about her—what it was about Stephanie Lee that inspired the devotion of so many that she met. It's a hard question to answer without relying on a list of adjectives, without saying that she was beautiful, and brave, and willful, and strong. She was all those things, but those things in themselves don't inspire scientists to devote month after month searching for ways to treat her, or hospitals like Mount Sinai to spend hundreds of thousands of dollars caring for her, or people she'd just met to keep daily vigils in her hospital room, or musicians like Ben Harper to dedicate songs to her, or for two journalists to become involved with every aspect of her life. Mark says it's because she never asked for anything, except a supply of Dr. Pepper that had to be continually replenished, no matter what time of day or night. But that's not true. She asked for everything, because she asked for love. So many people had failed her in the course of her life that she was naturally distrustful. But if you loved her—if you showed her you loved her by giving her exactly what she asked for, nothing more and nothing less—she gave you her trust in return, and by the softening in her ever-vigilant eyes let you know it was the only gift she had to give, purchased dear.

It's what makes this story so hard. She trusted us. She trusted Sinai. She trusted Eric Schadt and the promise of personalized medicine. It wasn't that she rested all her hopes on a cure—she was too smart for that, too much of a realist. But she liked the personalized part of personalized medicine. She liked that people she knew and respected were working for her, and for her alone. It made her feel less like a number. It made her feel less isolated. It made her feel important, special, and, yes, loved. She suffered terribly. But she was willing to suffer if it meant something—if she meant something in the grand scheme of things and wasn't just another person dying of cancer.

***

Here is a moment—just a moment—in the life of Stephanie Lee:

It came in Palm Beach, Florida, and in many ways, it was her moment—as good as it ever got, a fulfillment of a promise though not, alas, of promises. It was February 19, 2014, eight months after she received her terminal diagnosis. She was, for one thing, alive. She was, for another, as healthy as she would ever be—she had responded to the conventional chemotherapy and liver resectioning that constitutes the standard of care for metastatic colon cancer, and her CT scans and blood markers showed her to be nearly cancer-free. And she was happy, for she had started to enjoy the life she had gained as the "Patient Zero" of the article Mark and I published in the December 2013 issue of Esquire. The week before, she had been flown to a party in Austin, and there she'd met Lance Armstrong, whom she and many other cancer patients still greatly revere. Now she was staying at a historic Palm Beach hotel, in a room that was practically her own villa, with a walled patio. She was eating in a restaurant bearing the name of a famous New York chef, and—as if to prove her standing as the one natural aristocrat in a room full of rich people—was turning up her nose, with a literal crinkle and tiny pursed-lip shake of the head, at most of a $500 meal. . . .

She was on Sinai's tab. She was Sinai's guest—as were we—as a participant in a fundraising event scheduled for the next afternoon, a panel discussion intended to inspire an audience of heavy hitters to help bankroll Sinai's aggressive investment in personalized medicine. And so in the morning, after breakfast on her patio, she put on a pink blouse printed with the image of a butterfly and talked to a film crew Sinai had commissioned for the occasion about all Sinai had done for her. It was a lot. Since first receiving Stephanie's blood and tissue samples, Eric Schadt had successfully sequenced the genome both of her tumor and her germ line, which is to say the genes she was born with. He had identified the genetic mutations driving her cancer, and another scientist, Ross Cagan, had used those mutations to create a simulacrum of her tumor in a fruit fly for the purpose of testing a wide variety of treatments against it. Ross called his fly model the "Stephanie Fly." There had also been the "Stephanie Event," which was the meeting during which Sinai oncologists formally recognized the clinical potential of Schadt's and Cagan's brand of personalized medicine. There was also "Team Stephanie," which is what Sinai called Schadt, Cagan, and the oncologists who had started consulting on her case. There was, however, an absence—an omission—that troubled Stephanie, and when she got on camera, she asked about it.

"What I want to know is what I need to do to get treated," she said. "What I want to know is what I need to do to get in."

***

The practice of personalized medicine has a way of getting personal. It calls for patients to be treated in accord with their own specific genetic fingerprints and signature; for patient A to be treated somewhat differently from patient B; for patient A's and patient B's colon cancer to be treated rather than colon cancer itself. Because under the assumptions of personalized medicine, there is no such thing as a "typical" disease, there is also no such thing as a typical patient. Doctors have to get to know their patients' genetic information from scientists, and scientists have to get to know patients in a way that often goes well beyond the level of intimacy—and distance—afforded by the lab.

As the dean of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, Dr. Dennis Charney had to make a commitment to personalized medicine without knowing who might benefit from it. It was his job not only to see the future but to make sure that Mount Sinai had a place in it, and to that end he has built what he calls an "entire infrastructure" devoted to making good on personalized medicine's promise. "We've invested an enormous amount in genetics. I don't know what the exact number is, but it's well north of $100 million." He has put Sinai's money not only into a supercomputer and into an independent gene-sequencing facility; long before he heard anything about Stephanie Lee, he hired Eric Schadt and Ross Cagan.

Charney never met Stephanie. Nor did he ever meet Mark Beeninga, who was the first patient treated by a combination of compounds screened by Ross Cagan's fly model, or a young Italian girl whose treatment for glioblastoma was predicated on Eric Schadt's genomic analysis. But he was aware of them, and aware that "many of the investments we made came to bear" in trying to help them. Then, last year, he found out exactly how personal personalized medicine could be. It wasn't just that Mark Beeninga and the little girl from Italy died. It wasn't just that Stephanie kept getting sicker. It was that both the promise and the limitations of personalized medicine came home.

"During the fall, I had a granddaughter who was born with a very serious genetic deficit," he told me when I visited his office. "I'll show you her picture." He handed me a framed photograph of a dark-haired baby girl with a limpid gaze. "So this was my granddaughter," he said. "She didn't make it. She did not make it. She was born with a surfactant deficiency—very rare, one in a million. She was born in Mass General. So I started thinking—'This is my granddaughter. How am I going to help?' So I asked Eric—Eric Schadt. I said, 'What do you think? Look at the pathways and maybe you'll find some unexpected treatment.' There was no real treatment, only supportive treatment. So we did a little bit of what we did for Stephanie. Eric came up with a long list of possible genes active in the pathways. I had the doctor at Mass General who was treating her get involved with Eric, get involved with some drug companies. I was desperately searching for a new treatment. But we ran out of time. I knew what we were going through trying to help patients like Stephanie, and I saw the potential personally, but we ran out of time."

That Charney remains undeterred by his loss, and by the losses of patients who stood as emblems of personalized medicine's early potential—that, indeed, he continues to make personalized medicine his personal mission—says something about his deep grounding as a research psychiatrist and his understanding that all scientific progress rests on a foundation of setbacks and failures. But it also says something about the money and brainpower already devoted to personalized medicine, which has emerged as a combination of new faith and gold rush for a data-driven age. Calling it precision medicine, President Obama extolled its potential in his 2015 State of the Union Address and then ten days later announced a $215 million Precision Medicine Initiative, with its goal of sequencing a million American volunteers through the auspices of the National Institutes of Health. Google, Apple, and IBM all have their own initiatives, based on the idea that no data is more essential or valuable than the data generated by the human body. There is indeed a sense of inevitability to personalized medicine's rise, a proud sense that machines have finally gotten smart enough to understand how complicated each one of us is, how endlessly and fascinatingly and irreducibly complex.

But Stephanie Lee was one of the first. You have to understand that if you want to understand what she went through, the hopes and promises she had to endure. She was the second cancer patient in the world whose tumor was sequenced and then re-created in a fly. She was not part of any existing treatment protocol; she did not join others in a clinical trial; anything that Eric Schadt and Ross Cagan did with her they learned how to do through her. Team Stephanie? She taught Team Stephanie, and what she taught them, most of all, is that the standard of care—surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation—is not going to give way to personalized medicine without a fight.

***

"What do I need to do to get treated?" Stephanie had asked in Palm Beach, and it was a question she never stopped asking, because the answer never made any sense to her. For her to be treated, she had to suffer a recurrence. She had to get cancer again. She hated the standard of care: hated the FOLFOX chemotherapy treatments she received every other week and feared the despondency and fatigue they unleashed in her. They made her want to cry, and worse. But they'd worked. Her numbers were way down. Maybe the chemotherapy worked too well, because now the standard of care had to fail before Sinai could treat her. She had to start dying for them to be able to make her well.

That's what Team Stephanie had said, anyway, almost from the beginning, almost as they began consulting on her case. They'd even had a big meeting about it, all the oncologists who wanted to start working more closely with Eric Schadt and Ross Cagan. That was the Stephanie Event. They wanted to start using the treatments indicated by the sequencing done in Eric's lab and the modeling done in Ross's, but those treatments were still experimental, with no data and no statistics to back them up. The doctors all wanted to replace the standard of care. But as primitive and cruel as the standard of care is, at least it was proven to extend patients' lives, within certain predictable parameters. It was predicted to allow Stephanie to live almost another two years. They couldn't ask her to give that up for what could turn out to be a dangerous fantasy.

It felt as though they were asking her to take a test that she had to fail in order to pass. But they were all so confident. When she went to Palm Beach to appear at the fundraiser, she approached a member of Team Stephanie after the event, Dan Labow. He was the head of surgical oncology at Sinai, and she'd always liked him. He was always attentive to her. He was a compact man who'd operated on hundreds of cancer patients but still had the bright face of a boy, with an undimmed light in his eyes. She asked him if she could take a break from chemotherapy for a while, because of what it did to her. He'd surprised her by saying sure—"If the cancer comes back, it will present itself, and at least we'll know what we're dealing with." And Ross Cagan had said they were ready—they were ready for her when the cancer returned.

And then it did. It returned three weeks after Palm Beach, in the form of lesions on her liver. She decided to forgo chemotherapy and go back to Charles Conway, the surgeon at Ochsner Medical Center in New Orleans who had resectioned her liver in the fall. It turned out to be a fateful decision, because the chemotherapy she was receiving before the operation turned out to be the last round of chemotherapy she would ever be able to complete. The surgery went well, but the recovery didn't. She began experiencing abdominal pain. She began dealing with a devilment of a sensation, the feeling that she never successfully completed a bowel movement. She began bending over as she walked, like an old woman. So she went back to the hospital at Keesler Air Force Base, in Biloxi, where her cancer had been diagnosed, where the tumor on her colon had been surgically excised, and where she'd gone for chemotherapy. And she remained in the care of her first oncologist, Major Owen Roberts.

It was always the flaw in Sinai's approach to Stephanie's care—the fact that the members of Team Stephanie didn't actually care for her. The scientists devised treatments for her, and the physicians were apprised of what was going on in the e-mails that Mark and I sent them, offering occasional consultation in return. But while Team Stephanie was in New York, waiting for the standard of care to fail, Stephanie was in Mississippi, enduring its failure. The disconnect was fundamental and devastating. Team Stephanie was made up of scientific and medical minds who were trying to do nothing less than reinvent cancer care. Team Keesler was rooted in a troubled system of military hospitals investigated last year by the Department of Defense, with Keesler's own mortality ratios deemed "worse than expected" in the DOD's report. Stephanie found herself in Team Keesler's hands.

We called it the Death Factory, Mark and I. Not Keesler, but traditional oncology in general. And not because we suspected that anyone wanted Stephanie to die or worked out of malign intent, but rather because we knew that they believed that dying was what you did if you were as sick as Stephanie was—that everybody died, and that cancer always won. In March, we began sending e-mails to Dr. Randy Holcombe, the presiding clinician on Team Stephanie and an oncologist of unquestioned eminence in the field of colorectal cancer, pleading with him to become Stephanie's admitting physician rather than simply an interested onlooker. From the beginning, that was the plan as described to us by Eric Schadt—Randy Holcombe would be her "accepting physician"—and now we urged the doctors at Sinai to make good on that plan and that promise. We even began trying to convince her military insurance company to agree to pay for her treatment at Sinai if she were to be admitted. And we began to sound a little desperate, because even as we were asking Randy Holcombe to take over her care, she was being cared for by Keesler, where she was in terrible pain; where she was being told that her problem was nothing more than scar tissue or simple constipation; where night after night she was desperately checking into Keesler's emergency room and being sent home with nothing but laxatives.

She was not simply sick. Her CEA count—the most useful blood marker for colon cancer—had dropped to nineteen when she visited Palm Beach. By the end of April 2014, it had climbed back to eighty-six. A scan revealed a blockage in her descending colon, which Dr. Roberts proposed to treat with radiation and as much chemotherapy as she could tolerate. She feared the chemotherapy. But Dr. Roberts assured her that the radiation would have minimal side effects and help with her pain. Without delay, he scheduled five consecutive treatments for her with only a weekend's respite, and after the first one, Stephanie told Mark that it wasn't so bad: "You just lie down in a darkened room with a ceiling illuminated like the night sky, and the stars are so pretty."

She completed the radiation therapy on May 13, but the pain didn't go away or relent. It intensified. It began to crumple her and torture her and reduce her at night to a shuddering heap, curled in the fetal position on the bathroom floor. Her daughters, Kamri and Marchelle, would find her in the morning. She went to the hospital; she tried to go to the hospital, night after night, only to be sent home. Once, she was admitted only to be discharged by a resident who scolded her that she wasn't "sick enough."

"I'm dying of cancer, and he tells me I'm not sick enough," she told Mark. "I can't eat for the pain, and he tells me I'm not sick enough. Kamri is fussing at me that I have to take the appetite stimulants because I'm losing weight. 'You need to take those pills because I can see your spine,' she told me. But I'm not sick enough for that man."

***

On May 27, Mark and I both traveled to Ocean Springs for Kamri's high school graduation. She was a junior, but when she'd learned of Stephanie's illness, she had intensified her course load so that her mother could see her graduate. It had been one of the occasions Stephanie used to keep herself going and to see her way, somehow, into the future. Now it had arrived, and in all the photographs there is Kamri, in every way a match for her mother, in her slight stature, her strength, her determination, her vigilance, and her capacity for a sort of warrior's joy; and there is Stephanie, wincing, in her sleeveless floral dress and her sheen of glamour, and looking off to the side, as if she'd just noticed a beckoning shadow away from the lens, a few steps out of the frame.

She was contending not simply with the pain but with her knowledge of what the pain signified, and before Mark returned to New York, she asked him to take away her handgun and deliver it to the sheriff. I stayed in Ocean Springs and accompanied her when she visited Dr. Roberts at Keesler. She had never quite trusted him, ever since he'd delivered her original prognosis in what she regarded as a heartless way and ever since he'd refused to let her see her first CT scan. On this day, however, he was tremendously solicitous of her while at the same time adopting a posture of laid-back intimacy, leaning back in his chair and crossing his sneakered feet, pleased to see her, yes, but also apparently pleased that she had come to see him.

"Do you still have thoughts of hurting yourself?" he asked.

"Of course I do, with what I've been through," Stephanie said. "But I would never take my own life. I couldn't do that." Then she told him about the night the resident sent her home, and began to cry.

He handed her tissues and apologized for the resident's behavior—"What he said wasn't appropriate. In fact, it really pisses me off." But when Stephanie asked if the standard of care had failed, he came forward in his chair and reproved her with a sudden snap of authority. "You're still well within the standard of care. In fact, the only times the cancer has progressed are the times when you've gone off the standard of care to pursue a cure." He put air quotes around the last word, in case she'd missed his skepticism about the entire idea. "Well, the surgery you had only has a 15 percent cure rate. And now the cancer's back. So you probably won't be getting surgery again."

He recommended a new and aggressive course of chemotherapy, including Avastin. The previous summer, he'd put her on Avastin when she was having her period, and she had to be hospitalized because of blood loss. Now she told him that she wanted to go to New York and visit Sinai, and he said, "If you want to go up there and see what ideas they have now, fine. But it's not worth delaying your treatment. The last time you went to New York was easy. You're a lot sicker now. It's in your liver. It's in your lungs. And they don't have anything for you. They don't even have a clinical trial."

Stephanie had always thought that Dr. Roberts—who declined comment for this story—resented her relationship with Mount Sinai. She believed that, above all, he wanted to keep her at Keesler, and get the chance to prove himself to her. Now he spoke as if he had been right about her prospects all along, and it's difficult to admit, even now, that in fact he was.

***

A week later, a friend of Stephanie's (and a fellow cancer patient) left her doctor's appointment at Ocean Springs Hospital and thought of Stephanie. Stephanie, Kamri, and Marchelle's rented house was nearby, and the friend figured she'd drop by to see how they were all doing. She arrived to find the girls in tears and Stephanie curled up on the bathroom floor, bleeding from the nose and mouth. She'd broken out in a rash before she'd resumed chemotherapy. It had manifested itself on the palms of her hands, and she'd shown it to Dr. Roberts, worried that the chemotherapy would exacerbate it. The rash turned out to be a dangerous case of erythema multiforme. Within a day of her treatment, it began spreading into her mouth and nose, until at last she couldn't eat, couldn't drink, couldn't stand, could barely speak. Her friend called Mark and put Stephanie on the phone with him. He told her that she had to go back to Keesler, and she begged him not to make her go back there.

"They'll just send me back home!" she cried. Stephanie had gone to Keesler the night before, and they had once again sent her home in acute distress. The friend took the phone and told Mark about her own oncologist, Brian Persing, at Ocean Springs Hospital. "Take her to the emergency room at Ocean Springs," he said. It was the end of Stephanie's relationship with Owen Roberts and Keesler, and the first medical decision Mark had made on her behalf.

***

Three weeks earlier, on Tuesday, May 6, just after seven in the morning, Mark Warren had sent an e-mail to Dr. Randy Holcombe at Mount Sinai, copied to each member of Team Stephanie. It contained the news that Dr. Roberts had found "a new mass growing in her descending colon" and had "scheduled her to begin radiation at 9:00 a.m. this morning, Biloxi time." A few hours later, he wrote to Eric Schadt with a message for Drs. Holcombe and Labow: "Please advise Dan, Randy, and the team that the doctors at Keesler did the mapping for her radiation today, and that the actual radiation therapy starts tomorrow. The plan is for five consecutive days of radiation, followed by a two-day break and then a resumption of chemotherapy. Stephanie would very much appreciate any thoughts or second opinion Randy might have about this proposed course of action." A few days later, on a Friday, he corresponded directly with Dr. Holcombe and told him that Stephanie had received "radiation daily" throughout the week and that after a weekend break, she was "scheduled to finish her first five radiation treatments on Tuesday." Dr. Holcombe wrote back: "Are five radiation treatments all that are planned at this time?"

It seemed an unremarkable few days of correspondence, part of the back-and-forth that had evolved between Mark and members of Team Stephanie as Mark had evolved into Stephanie's official advocate, with a signed health-care proxy. We didn't know that it was anything but unremarkable until, at the end of June, Stephanie traveled to New York to be evaluated by the members of her team. Mark and I accompanied her and were surprised to hear from Ross Cagan that Randy Holcombe had strongly disapproved of Dr. Roberts's decision to irradiate Stephanie's abdomen and was, in fact, "ranting" about it. We were surprised when we visited Dr. Holcombe to hear him tell Stephanie that "radiation to the abdomen is pretty toxic," and he believed that "a lot of your symptoms are related to the radiation." Radiation inflames, radiation scars, radiation creates adhesions, radiation damages nerves and blood vessels, radiation wreaks such havoc on abdominal tissues that it works best when shrinking tissues due to be excised surgically. Not only does radiation rarely offer a benefit commensurate with its potential for damage, worst of all, it's irreversible. Indeed, the American Society of Clinical Oncology has said that radiation is "rarely used" for the treatment of colon cancer, although there are "specific situations when a doctor may recommend it." And there, that afternoon at Sinai, Dr. Holcombe said, "I haven't given radiation for colon cancer in years. It's not something I normally do. Because this is what happens. People get really sick."

Since Stephanie Lee had first met Eric Schadt and Ross Cagan, she'd had high-level scientists working on her behalf at Mount Sinai. What she needed, quite simply, was a doctor—and in that regard she could have hardly done better than Randy Holcombe. But he was also a doctor navigating his own transition from the standard of care to personalized medicine, and so was the soul of caution. "He is the most negative person I know here," Ross Cagan said at the time. "His first reaction is No. But that's a good thing. Because if we can convince Randy, we can convince anybody."

Holcombe's reserve extended not only to the innovations of personalized medicine but to every aspect of his relationship with Stephanie and to the very face he projected to the world. He wore a simultaneous air of absolute confidence and absolute weariness. He had seen a lot of death as an oncologist—"I have more patients die in a week than the average GP does in an entire career," he told us several months later—and his eyes viewed the world from a certain remove, under gray-blond hair parted carefully to the side. And so he stayed involved with Stephanie's case but not with Stephanie; he never failed to answer our e-mails but did so tersely and without elaboration; and he did not intervene even when Stephanie's doctors in Mississippi proposed a treatment he thought calamitous.

Indeed, Stephanie had traveled from Mississippi to New York with the hope that Holcombe would become her doctor and that she would become his responsibility. But now, at the end of her visit to his office, he said, "Stephanie, I'm going to give you a few suggestions. You can take them or leave them, because I'm just a consultant."

His suggestions were, as always, sound and provided a clear path forward. Stephanie would resume chemotherapy, with Brian Persing; Dr. Holcombe would consult with Persing and tell him when Sinai had a treatment for her. "And if Stephanie comes up here for treatment, will you be her admitting physician?" I asked. There was a silence, and then Randy Holcombe said, "We'll sort it out when the time comes."

***

E-mail from Mark Warren to Team Stephanie, dated July 30, 2014:

"Hello all. This evening, Tom and I write with an update on Stephanie, and with an urgent plea.

"It has been a month since Stephanie was last at Mount Sinai, and we need to tell you that her condition is now dire.

"For the past couple of months, and since her visit here, she has been experiencing episodes of intense abdominal pain. Managing the pain has required a doubling or trebling of her medications. A CT scan taken a few weeks ago (that Drs. Holcombe and Labow received last week, and can speak to better than we can) shows that the source of the pain is some sort of blockage in her colon, caused either by scarring from this spring's radiation or by cancer. . . .

"Her CEA count as of ten days ago stands at 197, the highest it has ever been. . . .

"And so perhaps not surprisingly, her CT scan—and a brand-new scan taken Sunday—also shows that her cancer has spread, with more spots on her liver and several in her lungs, including one which yesterday was described to her by the surgical oncologist at Ocean Springs Hospital as 'large. . . .'

"When Stephanie came to New York a month ago, she expressed her fervent desire to be treated at Mount Sinai, and to make the transition from the standard of care to the alternative therapies being researched for her at Sinai. It was generally agreed on at that time that after an assessment of her condition, some kind of appropriate near-term chemotherapy was in order to combat the cancer while the alternative possibilities were refined by Ross's team through the screening process with the fly model (Stephanie Fly 2.0). At the time, Dr. Holcombe estimated a two- to three-month time frame for this process to play out. The aforementioned blockage has made any chemotherapy treatment impossible in the intervening weeks, and so assuming that she gets some measure of relief from the blockage this week, some form of treatment will be urgently needed while the screening process continues. Yesterday, we visited Ross's lab and were apprised of their progress and their projections. They are working on Stephanie Fly 3.0, and it will take at least two months for the drug screening to be concluded. We understand that the biological processes of their work simply cannot move any faster. We also understand—and hope you understand—that Stephanie is running out of time. . . ."

***

When Kamri had trouble with her homework, Mark did it with her. When she had trouble with school administrators, he talked to them. When Stephanie brought her truck to a car dealer for routine servicing and was talked into trading it in for a brand-new car and a seventy-two-month loan that she couldn't afford, he called the owner of the dealership, explained her situation, and by the time they were done, the man paid off the loan and gave her the car. When she overextended herself on her credit cards, he called the credit-card companies and asked them to forgive the debt. When Stephanie's landlord sold her house out from under her, he shamed her into giving Stephanie extra time to move. There was simply nothing he wouldn't do for her or her daughters, no fight he wouldn't take on, no errand he wouldn't perform, no e-mail he wouldn't write, no phone call he wouldn't answer, no matter what time of day or night. It is hard to judge anyone else who appears in this story, because his devotion represents some kind of absolute, but it is also hard to judge him, because there's no accounting for absolutes—because his devotion seemed at times like both an obliteration and a completion of himself, a process that, once started, had to be seen through. And so when he visited Stephanie in August, to be with her after a surgeon at Ochsner installed a metal stent in her intestine in order to resolve her blockage, and he found her in her house nearly passed out with pain, he couldn't know what had happened—he couldn't know that the stent had failed and was pinched at the top—but he helped her to his rental car and drove from Ocean Springs to the hospital in New Orleans at one hundred miles an hour, singing to Stephanie Lee the whole time.

***

Ross Cagan never had a problem with commitment or with confidence. Indeed, his confidence was like his clothes, something that set him apart—a scientist who dressed as though going out for a night of hipster bowling. He was tall, narrow, goateed, ironically polyestered, and he spoke of his intelligence in frank terms; as such he offered an eternal counterweight to the endlessly collaborative Eric Schadt, who was squat, spit-curled, bustling, and wore a uniform of khaki shorts and a white polo shirt no matter what the weather or the occasion. Cagan would be the first to tell you some things about himself—that he had worked in the lab of a Nobel Prize winner who had named some of the signaling pathways fundamental to the malign transformation of healthy cells—and when he sat down with Schadt, Stephanie, Dan Labow, and Sinai president Ken Davis at the Palm Beach fundraiser, he announced that he thought he might have "broken" colon cancer. A few minutes later, when the conversation turned to his guitar playing, I asked him to name his heroes. "I'm too arrogant for heroes," he said.

And yet, by last summer, he had been humbled by both Stephanie and her cancer. He and his lab had built a series of fly models for her, each of increasing complexity and specificity, each loaded with more of her mutations than the previous iteration, each Stephanie Fly closer to the essence of what was tearing Stephanie apart. Stephanie Fly 1.0; Stephanie Fly 2.0; Stephanie Fly 3.0: What they all had in common were the tumors that Ross Cagan had given them, and their dim prospects. "The tumors kill the fly," he explained later. "What was killing Stephanie killed the fly. Having a big tumor in the gut kills the fly."

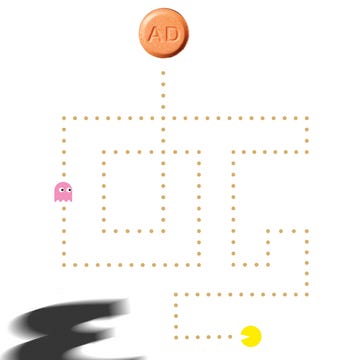

Cagan's idea, however, was not to kill flies—it was to save them by seeing how they responded to a vast library of FDA-approved treatments. He wasn't looking only at drugs that had already been indicated for use against colon cancer; he was looking at everything in order to find anything at all that worked, especially in combination. The drugs he tested, as he would later write, had been "approved for diseases across most classes, including cancer, neurological diseases, cardiovascular diseases, infection, inflammation, diabetes, endocrine diseases, respiratory problems, and even digestive issues. By themselves many of these drugs may not have shown much activity against cancer, but we are hoping to find cocktails with unique activities." Although intended to embrace complexity, his screening process was also ruthlessly empirical: "We feed the fly the drug, and after six days we look, and if something is alive, that's a hit."

A hit: how he, and Stephanie, would come to live for that word. He thought he had one with an early version of the Stephanie Fly, but that fly model was too simple—everything worked, and then when he added another mutation, nothing did. Then he found a drug that seemed promising until the company that made it stopped making it. And then with Stephanie Fly 2.0, he had what he calls "a weak hit that didn't really hold up. It was a crappy hit, and that was when we thought of abandoning the whole thing."

That he didn't is testament not only to his commitment to his fly model but also to Stephanie: his awareness of her intensifying agonies. He had thought she, and he, had time. Eight months earlier, the clinicians gathered for the Stephanie Event had given him a guardedly optimistic prognosis, based on the expected outcome of her first liver surgery and her response to the standard of care. Now Mark was sending him e-mail after e-mail recording her nearly daily decline, and Cagan realized that the timeline, as he called it, had collapsed: "This woman went from, 'No problem, she has three to five years,' to, 'She's desperate, can you help us?' "

He proceeded with his screening, weak hit and all, and when Mark visited his lab in late July, he learned that it would be at least two months before the Stephanie Fly 2.0 would yield a result. Then we began hearing that he was working on Stephanie Fly 3.0 because the hit from Stephanie Fly 2.0 "didn't validate"—because he'd modeled the tumor based on information from Schadt's lab derived from a tissue sample of insufficient purity. He had to start over again, and on September 10, I received an e-mail from Eric Schadt:

"Tom, talked to Ross. The news not so great. The straight answer is that they carried out the rapid screen on a focused set of compounds and they got no hits on the Stephanie fly 3.0. Ross characterizes Stephanie's tumor as a 'tough combo.' He has started a more expansive screen, but unfortunately that is not a fast process given it is a much broader set of compounds (6 weeks)."

By this time, Stephanie's CEA count had risen to eight hundred. By this time, she had tried to resume chemotherapy, but the initial round had left her so weak that Brian Persing, her doctor, was switching treatment protocols. By this time, Mark and I began to fear that Stephanie was going to die without ever being treated by Mount Sinai and began asking Team Stephanie to put us in touch with doctors conducting clinical trials relevant to Stephanie's cancer.

A year had passed since Sinai had sequenced Stephanie Lee's tumor, and we had nothing—Stephanie had nothing, and we had to start from scratch. Back in July, Schadt's lab had issued a report with findings and recommendations based on its genomic analysis of Stephanie's tumor, and we had barely noticed it in our fervor to push Ross Cagan to finish his work with the fly. The report had recommended that Stephanie explore her eligibility for clinical trials investigating a class of drugs known as MEK inhibitors—but for all we knew of MEK inhibitors it might as well have urged us to look into the efficacy of baby aspirin. Now the report was all we had, and when Eric urged Mark and me to "shop it around," we did so, dutifully calling investigators at MD Anderson and Johns Hopkins who with all due respect let us know they were accustomed to talking to physicians, or at least people who had some idea of what they were talking about.

It was early October when Mark received a call from Marshall Posner, an oncologist from Mount Sinai, checking in on Stephanie's condition. Posner was working with Ross Cagan, and he wanted to know if Stephanie was still healthy enough to tolerate treatment.

A fly had lived.

Ross had a hit.

***

It is one thing to endure pain. It is another to have hope. But the fear that Stephanie was enduring pain because she had hope—because we had given her hope, had insisted on hope—made us reconsider what we were doing. "You don't have to do this for us," Mark and I both eventually told Stephanie. "You don't have to keep on fighting because you think you owe us something. You don't owe us anything. We owe you." Pain and hope had become hopelessly entangled, and there was a level of horror, and terrible consequence, to the prospect of telling Stephanie to hold on because help was on the way.

Text from Stephanie, two days before Thanksgiving:

Sinai's not going to hurry are they Mark?

Text from Stephanie, Thanksgiving morning:

I can't do this anymore I can't take this pain. I'm sorry, Mark.

She wasn't even texting him from home. She was texting from Ochsner, in New Orleans, where she lay in bed, alone. Her stent had failed again; more precisely, her tumor had claimed it, wrapping its greedy fingers around its metal throat. She was scheduled for another surgery. Back in August, when Dr. Persing had first sent her to Ochsner, he had sent her for a surgical bypass, also known as a colostomy, and to have the tumor "debulked," or cut away, to make a passage and restore function to her GI system. The attending surgeon had installed the stent instead. Now Persing was trying again to get her an ostomy, in the hope that it might win her some comfort, though she'd have to wear a bag for her waste.

On the day after Thanksgiving, Mark flew down to New Orleans so that Stephanie wouldn't be alone in the hospital for the weekend. She underwent surgery that afternoon and woke up not with an ostomy but with a second stent. Back in Ocean Springs, Dr. Persing had been sensitive to her pain and had given her doses of Dilaudid that might have killed her had she not developed a tolerance for it. He had sent her dosage information to the doctors at Ochsner. But they had either not read what he wrote or not believed it, for they looked at the eighty-five pounds of Stephanie Lee in their care and decided that no woman so small could survive so large a dose of opiates. They treated her pain as if to wean her from her pain medications, as if there were a moral component to pain management. Mark, at her bedside, had never seen another human being in such pain, for it was not just pain with no end, it was pain with no limit. She writhed with silent screaming, and he became the haunted figure roaming the empty hallways, looking for someone to offer Stephanie relief.

Text from Mark Warren, the Saturday after Thanksgiving, middle of the night:

These fuckers do not learn and they never act as with any urgency. Her nurse is terrible, so I went to the charge nurse and demanded to talk to the doctor. Just finally talked to the fucking doctor after waiting forever, and got him to agree to bump her dosages. And THAT was 20 minutes ago, and nothing. I am about to start breaking shit.

She asked the doctor, Do you guys think I'm a pill head or something? Why won't you treat my pain?

And yet even as Stephanie underwent her holiday-season ordeal, I was corresponding with Ross Cagan about the prospects of her receiving treatment. He had written on Thanksgiving Day about not only the technical challenges he was facing as he screened his flies but also about the funeral he'd attended for Mark Beeninga. He had screened flies for Mark; he had come up with a treatment for Mark; he had given Mark hope. And so he had gone to the service "wondering whether our failure to cure Mark would make the funeral awkward." It had not; indeed, Beeninga's wife had told him to keep going, to keep pushing, to keep moving forward.

"We are screening Stephanie's avatar until we hear otherwise," he concluded, and I wrote him back telling him that Stephanie was planning to come up to New York for Christmas. "When [Dr. Posner] first inquired into Stephanie's health eight weeks ago, Mark and I thought there might be reason for hope. We pray there still is—hope that Stephanie might still be connected to your great ongoing enterprise at Sinai. . . ."

But if hope and pain were intermingled in the person of Stephanie Lee, so were faith and science. She was raised in the Pentecostal church and could recall with tearful immediacy the strictures it placed upon her: "I wanted to be a sprinter in high school, because I was fast. But they wouldn't let me. They wouldn't let me wear shorts. I had to wear a dress. . . ." She was no longer a churchgoer. But she loved her Lord, and she loved her Bible, and she often called upon the first and remembered the second when her pain rose to its greatest intensity. Her faith never took the place of her trust in what was being done on her behalf at Sinai; rather, it intensified it, and gave her belief in science a religious dimension. And yet when her pain immobilized her at Ochsner, it was the sight of the pastor of her mother's Pentecostal church that lifted her. He slipped in the room with his wife, and before Mark Warren knew who he was or what was happening, Stephanie recognized him and rose to her knees, there on her hospital bed. Her arms were as thin as dowels, and laced with all manner of tubes and hoses, but she threw them at him, over her bed's protective railings, and accepted the blessing he offered with silent tears.

***

"I've never been to a Broadway show. I think I'd like to go to a Broadway show."

She said this in September, when the sickness was spreading through her body, but before the shattering began. Mark had suggested she come to New York, with the girls, and the trip became one of her goals, one of the things that pushed her through the pain. But she had gotten sicker and sicker, until nobody thought it was a good idea for her to make the trip and nobody had the heart to tell her not to. She and Kamri and Marchelle arrived at LaGuardia on December 18, and of course Mark didn't just have three tickets for Cinderella for the next night. He had called the producers and made arrangements for Stephanie and her daughters to come backstage after the show and meet the star, Keke Palmer, in her dressing room.

They stayed with Mark's family—his wife, Jess, and his children, Zeke and Oona—in Harlem. But the trip had depleted Stephanie, and she took to Oona's bed and stayed there. The next morning, Mark brought her to meet Dan Labow, a member of Team Stephanie, at Sinai. He sent me this text before leaving: Just now, Stephanie, weeping, took my hand, and put it to her belly, like an expectant mother might do. I felt a fearsome lump, Tom. A terrifying presence.

Labow knew exactly how sick she was, and tenderly he took her ankles—already starting to swell—in his hands. "Am I going to die?" she asked. He answered that he didn't know, but held both her hands and said, "Whatever happens, we'll be with you every step of the way." She began to cry and to tell Mark, as if in apology, "I can't go, I can't go tonight, I can't go."

The girls went to Cinderella with Oona instead and met Keke Palmer backstage. On Sunday, December 21, I went to Mark's apartment with my family and my dog for Stephanie's thirty-eighth birthday. She stayed in her bedroom most of the time, and when she emerged it was as a woman much older than her years, with not only the tiny steps of the aged but the admixture of fragility and ferocity, the air of containment that both protected and demanded all that she had left. And yet still she saw everything happening in the room, particularly what lay out of the line of sight: "He never takes his eyes off you, Tom," she said of my dog, and when I gave her the standard answer—"He's a good boy"—she corrected me. "Oh, Tom," she said. "He your son."

The next morning, wearing the necklace that Mark and Jess had bought her for her birthday, she went back to Sinai for an appointment with a palliative-care specialist who changed her medications and began extending her the mercy of viewing her pain—and not her cancer—as her primary malady. When the appointment ended, Mark pushed her in her wheelchair to a car he had hired to take her home and then asked, "Are you up for not going home right away?"

He folded the wheelchair and put it in the trunk, then asked the driver to lower the windows and drive the car as slowly as he possibly could all the way down Fifth Avenue, which was to Stephanie's delight dressed up beautifully for Christmas. And they didn't stop until they reached the one place she most wanted to see, the 9/11 Memorial that she so closely identified with her husband Terrance's sacrifice.

The next day, she stepped out of the bathroom in Mark's apartment with her arms extended and her palms wide open. Twice she had tried to resume chemotherapy, and twice the demon of erythema multiforme had punished her for it, taking advantage of her hobbled immune system to invade her nose, her lips, her gums, her tongue, her throat. Now Mark sat at his dining-room table and saw that it had returned, with spots of it etched in the center of her palms like nails.

"I have to go home, Mark," she said.

***

She didn't go home. Not then. Mount Sinai admitted her on December 23, and she stayed five and a half weeks.

You could write the story of Stephanie's time in the hospital by all the things that went wrong with her and all the things that Sinai's palliative-care specialists, cancer specialists, kidney specialists, heart specialists, infectious-disease specialists, and gastrointestinal specialists did to help her.

You could write it by tracking the steady increase in the pain medications she required, the astonishing doses that she ended up taking.

You could write it by naming everybody who came to visit her and by saying that Mark's assistant at Esquire, Natasha Zarinsky, and her friend Vicky Jordan came to visit her every day, combing her hair, massaging her feet, holding her hand, helping her walk to the bathroom.

And of course you could tell it by telling the story of Mark. You could tell it by totaling the hours he stayed with her and the days he missed from work and the holiday celebrations he missed with his family. You could tell it by naming the reality-TV programs he watched with her or by listing the foods he brought her from all corners of New York City—the fried catfish and panfried chicken and chicken wings from Harlem, the chicken nuggets from McDonald's and the burgers from Burger King and the tiramisu from Mezzaluna. You could tell it by saying that if the bags of oatmeal cookies he bought didn't fit her increasingly particularized and fanatical standards, he kept buying them until he found the right oatmeal cookie, and then endured without complaint her accusations when he ate what she wouldn't—"Mark eating my cookies!" You could tell it by saying that, in the end, Mark's wife, Jessica, contracted C. difficile from her visits to Stephanie and had to go to the hospital herself.

You could tell it by repeating all the things that Stephanie said in her sleep and in her delirium, and that before she got her nephrostomy, she moaned, "I'm doing this for my kids! I'm doing this for my kids!"

You could tell it by painting the picture of Stephanie sitting at the edge of her bed, her feet dangling over the side, her hospital gown open, the tattoo on her lower back still declaring, in some Gothic font, GOD BLESS.

But really, it needs to be told in terms of the question that Stephanie asked almost a year earlier and kept asking, in one way or another, during the entirety of her stay at Sinai. What do I need to do? She never lost faith that her question would be answered, for she never lost faith in science or the scientists working on her behalf. But she would learn that faith in science is not so different from the faith she grew up in, dependent on forces bound by necessity and ultimately indifferent to the human need for miracles. So when, on January 21 of this year, she finally got an answer, it was no less befuddling than what she had heard back in Palm Beach. A doctor by the name of Krzysztof Misiukiewicz came to her room because he was in charge of the protocol by which the results of Ross Cagan's research with fruit flies found their way into patients. He was a wary, finicky man of saturnine countenance, but he believed he had a treatment with the potential to extend Stephanie's life. He even had the medicine from the drug company. But he couldn't give it to her, because she had been battling a kidney infection since the beginning of January, and she was simply too sick. "Not today, not tomorrow," Dr. Misiukiewicz told her. "Maybe the next day."

She had once been given to understand that in order to receive her treatment, she had to get sick. Now she had to get better, and three nights later she asked Mark to sit by her bed. She could barely speak, but he could understand her words clearly enough. "Mark," she asked, "have I been kicked out of the study?"

***

Back in September, we lost our faith in Ross Cagan's ability to find a new treatment for Stephanie with his fly model, and tried to find a clinical trial for her based on Eric Schadt's genomic analysis and its recommendation that MEK inhibitors might prove efficacious against her cancer. A month later, we regained our faith in Cagan and forgot about Schadt's analysis and MEK inhibitors altogether. After all, Cagan seemed to be doing something extraordinary in his lab, something heroic—he was never giving up. He had come as close as anyone ever had in seeing Stephanie's cancer face-to-face, and he understood, as he wrote to us, that it was driven by "a palate of mutations . . . somewhat unusual and particularly aggressive, a point that seems to be borne out by the growth of Stephanie's tumor."

He did not think that a MEK inhibitor would work against her cancer. "Stephanie had a ras mutation," he said recently. "It's one of the main drivers of cancer. She had ras, they all have ras. You turn on ras, you're going to transform cells." Since there are no drugs currently available that block the malign signaling of a mutant ras gene, many researchers have tried to target other points in the ras pathway, the MEK enzyme being one of them. "Basically, ras equals MEK inhibitors. If that worked, I wouldn't have to open my center"—that is, the Center for Personalized Cancer Therapeutics, which Cagan started at Sinai in 2013. "The whole purpose is to go beyond MEK inhibitors. Or if you're going to use them, use them in combination with other drugs, for synergistic effect."

In the end, he says, "we screened a hundred thousand flies against twelve hundred different compounds." And yet as late as Christmas Eve 2014, with Stephanie already admitted to Sinai, he sent an e-mail detailing what he had found for Stephanie in his lab: "Nothing." He was working with his labmates to make one of the fly models "more sensitive to rescue," but after that, he said, "we are out of fly tricks."

It is what made the events of December 29 so remarkable, and feel so nearly miraculous. When Cagan and Dr. Marshall Posner—the oncologist in charge of cancer clinical trials for Sinai—walked into Stephanie's hospital room, they might as well have materialized out of thin air. No one was expecting them, least of all Stephanie, and no one could have possibly anticipated Posner announcing that there had been a "very promising result" in Cagan's lab. Suddenly, hope had made its fraught entrance, causing one of Stephanie's oncologists to exclaim brightly, "Those fruit flies have been working so hard for you!" Cagan blanched at her comment, out of fear, as he said, of "overpromising." Later, Cagan met with Stephanie in private, and Stephanie reported to Mark afterward that Cagan had told her that he had found a combination of two drugs, the first of which reduced the size of the tumor in the flies and the second of which provided "a powerful one-two punch." Then on January 14, Cagan met with a panel of experienced clinicians who determined a protocol for administering the treatment to Stephanie. Since there were two drugs, she would take them in stepwise fashion, moving on to the second only if she tolerated the first.

The second was axitinib, used in the treatment of renal cancer.

The first was trametinib, a MEK inhibitor.

Ross Cagan has since described the "hit" that led to Stephanie's treatment protocol as very weak, "the best of a sorry lot." But the discrepancy between the excitement that attended its creation and the realization that it was never anything more than a long shot tells the story not just of Stephanie Lee in particular but personalized medicine in general. It is easy to get excited about personalized medicine, easy to accept its triumph as inevitable, easy to anticipate the miracles to come—all those big brains, all those Schadts and Cagans reinventing medicine on the fly, almost on a case-by-case basis, for the benefit of individuals like Stephanie, or Mark Beeninga, or the granddaughter of Dennis Charney: How can such an effort inspire anything but, well, belief? But personalized medicine is also nascent medicine, and if anything, its embrace of complexity has shown just how galactically complex the forces driving disease really are.

Personalized medicine even turns out to be ethically complex, as Ross Cagan found out on January 26, when Sinai's internal-review board conducted an ethics review of his participation in Stephanie's case. He was a scientist, not a doctor, and yet he was having contact with patients. He had to convince the board that he was not conducting a clinical trial it hadn't yet approved. He did, but when he left that meeting, it was with the understanding that Sinai had drawn a line against even the perception that scientists might be urging the results of their research upon Sinai's patients. Stephanie was still in the hospital and had, in fact, begun to die. But on the next day, Cagan wrote to Mark that "for Stephanie's sake, I am stepping away." An hour later, he materialized again in her room and told Stephanie's friend Vicky Jordan, "I shouldn't even be here." But that didn't stop him from hugging her, for the very last time.

***

The day that Cagan went for the ethics review happened to be the day that Mark and I stood outside Stephanie's hospital room and had to decide whether to approve the fecal transplant that might have resolved theC. difficile infection. We were aware that by now we were open to our own ethics review—we had already written a story touting the prospects of Stephanie's treatment and now had to make a decision on which Stephanie's prospects for treatment rested. As Cagan described himself as "all in on Stephanie," we could describe ourselves as all in on Cagan. We had believed, and Stephanie believed, and now, as we spoke to Dr. Grinspan—the expert in clearing C. difficile infections with fecal transplants—we could see into her room from our vantage in the hallway, fully aware of her presence just out of our sight. She was tiny, spindly, jagged, disheveled, lost amidst her bedding, wearing diapers. But she was still Stephanie. By God, she would always be Stephanie, forever the hopeful realist, and so she would always want the treatment she deserved. But in order to get that treatment, she would have to be pierced again, this time by the snake of a nasogastric tube that without anesthesia would deliver a parcel of possibly nausea-inducing fecal matter to her stomach. . . .

She had been tortured enough.

Two days later, we attended a meeting in her room that more closely resembled a religious service, all of us ringed about her bed, the palliative-care team, the oncologists, the residents, the chaplain, the social worker, Krzysztof Misiukiewicz, and yes, Eric Schadt, to hear Stephanie declare, in a voice softened and deepened by pain and exhaustion, her final intention:

"I need to go home to be a mother to my baby."

And that night, Mark sent me a text she had written a week earlier, after he'd texted her with the words, "Let's get you home, okay?"

They had been fighting, Mark and Stephanie. They were, in Mark's words, like an old married couple, and Mark offered the only outlet for her recriminations and accusations and obliterating torrents of despair. But now she wrote him back, as she wrote everything back then, slowly, against the steep gravity of illness, sometimes slumping into sleep between characters, and she wrote him this:

I miss my Marchelle and I miss hom. Thank you for the Love yours has shown to us. I love.

***

Death is the supreme ironist. It specializes in the long haul and is unblinkingly alert to what the long haul makes of human endeavors. We tried to save Stephanie Lee. We tried to inspire and challenge and prod and browbeat others into doing the same, and wound up taking our place in the ranks of those who devoted themselves to her, who worked ceaselessly for her, who did what they thought was best for her and came so close to success that they—we—each wound up doing our part in an annihilating failure.

There was some very important science committed in her name, an endeavor that gave purpose to her suffering and made her feel special, and much was learned from this failure that may well be turned to the benefit of sick people who come after her. For everyone who tried to be heroic for Stephanie, she herself was the hero. And there is no procedure that will take place in the name of personalized medicine at Mount Sinai that will not in some way bear her imprint.

When she finally went home, Stephanie was herself days away from receiving personalized, or targeted, therapy at Sinai. "A year later, everything might have turned out differently," Ross Cagan would say. With more time, Stephanie would have been one of the 150 patients Cagan says he expects to have soon in clinical trials at the Center for Personalized Cancer Therapeutics. But she didn't have more time, and so wound up the central figure in a drama that took eighteen agonizing months to unfold. In the end, the ironies were all that were left:

That the doctor in Mississippi who treated her with radiation and two devastating rounds of chemotherapy with Avastin was more accurate in his prognosis than the doctors in New York.That for all the brilliant scientists at her beck and call, what she needed at the most crucial junctures of her illness was the firm hand of a doctor.

That Sinai never treated her cancer but, when it was too late, threw every resource it had at her case without asking for a penny.

That the only miracles available to her turned out to be the human and ancient ones—friendship, loyalty, and love.

The ironies accrue like compound interest; the more one contemplates them, the more they keep propagating themselves, and if sometimes they are brutal, sometimes they represent a kind of justice, the sound of the universe clanging into place. "That's exactly the kind of patient we take," Eric Schadt had said when he first heard about Stephanie Lee, and so it was Eric Schadt, at the end, who signed the promissory note that allowed an air ambulance to fly Stephanie home to Mississippi, on January 29 of this year, five weeks and two days after she got too sick to make those Christmas memories with her girls and entered the hospital for what we all thought would be a short stay.

She was not alone, of course. She was with Mark Warren, at the end of his walk with her. He climbed into the Learjet with her, and sang to her, and spoke to her, and took her picture, wrapped as she was in sheets white as the Pietà, her face aged, ageless, whittled down to the beauty of her bones.

And when they touched down at the airport in Gulfport, Mississippi, there was an ambulance on the runway with its lights already whirling, as if waiting for the arrival of a dignitary. The ambulance would run its sirens all the way to Ocean Springs, and the traffic would part for her.

"You're home, Miss Stephanie," Mark said to her.

"We changing planes?"

"No, you're home. In Mississippi."

She looked out the window, to the light pouring in.

"For real?" she asked.

Stephanie Amanda Lee died on February 4, 2015, at Ocean Springs Hospital, in Ocean Springs, Mississippi.

Published in the August 2015 issue.