One solitary record changed Bill Harrison’s life. He was a 15-year-old lad from Liverpool, walking down to his local sports centre, when he heard a bewitching sound coming from someone’s window.

“I sat on the wall to listen,” he says, “and this chap came out in a beautiful midnight blue suit and a pair of oxblood slip-on shoes with a brass bull’s head on the top. I thought, ‘This fellow’s a film star!’”

He wasn’t a film star, though. He was a seaman – one of the famed Cunard Yanks, whose journeys took them around the world, giving them access to the records and clothes you could only buy in the US. The song that had transfixed Harrison was Settin’ the Woods on Fire by Hank Williams, which the mystery seaman explained he had found in Texas. He promised Harrison that such treasures awaited him, too, should he choose to join the merchant navy.

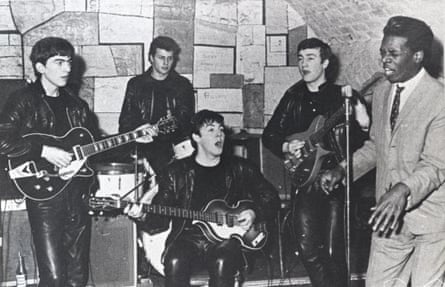

And so began a long career at sea in which Harrison and his colleagues performed dual roles: their day jobs (in Harrison’s case, working his way up the ship’s kitchens); and the arguably more vital role of bringing back American imports with which to wow the locals. These imports included everything from fridge freezers to Wrangler jeans, but it was the early rock’n’roll, soul and blues records that would really go on to change the course of history. Sam Cooke, Fats Domino, Buddy Holly, Roy Hamilton, Billy Eckstine: all these sounds were soaked up by the local musicians who would go on to form Merseybeat bands such as the Searchers, Gerry and the Pacemakers and – of course – the Beatles.

“Liverpool in the early 50s was a dark, bombed place recovering from the war,” remembers Harrison, of the decade before Merseybeat arrived. “The men were in army demob suits and old army overcoats. So going over to America was like Dorothy in the Wizard of Oz – black and white into Technicolor.”

It wasn’t hard to find the records. Harrison remembers plenty of stores selling jukebox returns – discs that had been out for two weeks and were already out of date in the fast-moving world of the US pop charts. It was a throwaway culture completely unlike post-war UK and the seamen bought them up, 10 at a time for around $2, to play back home in Liverpool. Did Harrison have any inkling that they were kickstarting a culture shift? “No,” he laughs, “it wasn’t on my mind at all.”

It took a couple of years before he started noticing the new music spreading across Liverpool and being absorbed into the performances of local bands who played at dancehalls such as the Grafton or Locarno. Things would soon become bigger than the local nighteries. Harrison tells a tale of bringing an album back by the Georgia-born soul singer Roy Hamilton, which opened with a cover version of a song from the Rodgers and Hammerstein musical Carousel. It eventually reached Gerry Marsden of the Pacemakers fame, who decided to perform his own version at a concert. A man collared him afterwards and asked him to record it. The man was Bill Shankly, the song was You’ll Never Walk Alone, and it would soon become the anthem for Liverpool football club, sung by the crowd before every home game. “Marsden puts very similar inflections into the song, trying to get it very similar to Roy Hamilton’s version,” says Harrison.

It wasn’t just the records that influenced the music scene. A lot of the seamen filled their time aboard by learning instruments, becoming great musicians and starting their own groups back in Liverpool, such as country group the Blue Mountain Boys. Harrison also remembers being at his friend Ivan Hayward’s house in 1961 when a knock came at the door. Outside stood a young kid – “greasy hair and black plastic clothing” – who’d heard Hayward was selling the black Gretsch Duo Jet guitar he’d picked up several years earlier in New York.

“Ivan told him he wanted £90 for it but the lad said he only had £70. So I told him to write an IOU on the back of the customs receipt – because I knew he’d need that if he ever took the guitar abroad.” He signed it “G Harrison” and the instrument became a staple of the Beatles guitarist throughout his career (you can see it on the sleeve for his album Cloud Nine). “Of course, we didn’t know who it was at the time because we hadn’t heard of the Beatles. And he never came back with the £20!”

Oh well, you can bet the receipt – which Bill Harrison still has – is worth more than £20 now.

The influence of those original rock’n’roll records is still alive today, and the Merseybeat sound has evolved and prospered in a lineage of Liverpool bands that runs through the La’s, the Zutons and the Coral. And if you were still in any doubt as to just how a simple record can change a life, then cast your mind back to the Hank Williams record and its seaman owner who came outside and convinced Harrison to go to sea.

“He came down with his girlfriend to help me get an application form,” he recalls. “And she brought her girlfriend along. We went out as a foursome afterwards and now, over 60 years later, I’m still married to her.”

Mersey me

Millstone or muse? What Liverpool’s rich musical legacy means to the city’s current crop of bands

Kieran Shudall, Circa Waves

Growing up in Liverpool, you definitely feel the presence of past fires. Every family occasion is soundtracked by the Beatles and every band wants to sound like the Coral or the Zutons. I remember putting out our track Getaway and it was reviewed on a round table show where someone said: “It doesn’t sound Liverpool enough - it doesn’t have enough harmonies.” I was like: “Fuck off mate!” Just because you’re from Liverpool doesn’t mean you’re restrained to sounding a certain way. I wanted to do something that didn’t sound like it was from Liverpool, to move away from that Merseybeat sound. In Liverpool the bar has been set really high - you’re up against the greatest rock’n’roll band that ever existed! It’s not demoralising, though, it’s encouraging. It’s like having someone really good on your football team you can always depend on.

Emily Lansley, Stealing Sheep

I was quite shy as a kid, always surrounded by lads with guitars and I think I found it hard to see how I would fit into the music scene. I ended up being drawn to the more alternative side, where there was more of a mix of men and women. The scene at the moment is really supportive and much broader. It’s not really based around a Liverpool sound any more – there are bands like Dogshow, who have a more dance/techno sound, or the Harlequin Dynamite Marching Band, who are like a New Orleans-style street band. Me and Lucy, our drummer, are from the city so we must be influenced by Liverpool’s musical history but it’s not on purpose. You hear the Beatles all your life and we looked at them recently and noticed just how unusual and surreal they are. There’s also just a real sense of music in Liverpool, the sense that it’s a musical city – there’s bands on and people busking everywhere. You do get a lot of merseybeat sounding bands but I don’t feel like people in our scene hark back to that at all.

Harry Chalmers, Hooton Tennis Club

You have little scenes in Liverpool, cosmic scouser, or Merseybeat, or whatever, but they’re more like little worlds you can look at from the outside. When we started, we felt no pressure to play a certain style. I don’t think many people do. Me and [singer] Ryan did a music degree here, which was more like a sociology/history thing, and you can’t help but get a little bored of the Beatles. You end up ignoring them for six months but then when you hear them again and you’re in the mood for it, it’s great. But that sound was never what we wanted to do. Because of the internet, your influences are no longer about what’s in the local record shop – they can be anything that’s ever been recorded. So if you had a big city like Liverpool making music that was all based around the same type of sound, it would be really scary and weird.

- 4 July is the 175th anniversary of the first transatlantic crossing in Liverpool. To mark the occasion, Liverpool City Council has organised a series of waterfront events. For more information, visit www.onemagnificentcity.co.uk