In the UK today, a young person is more likely to have a television in their bedroom than a father in their house by the end of their childhood. And even if fathers are around, their sons don’t engage with them much: boys spend 44 hours in front of a TV, smartphone or computer screen for every half hour in conversation with their fathers.

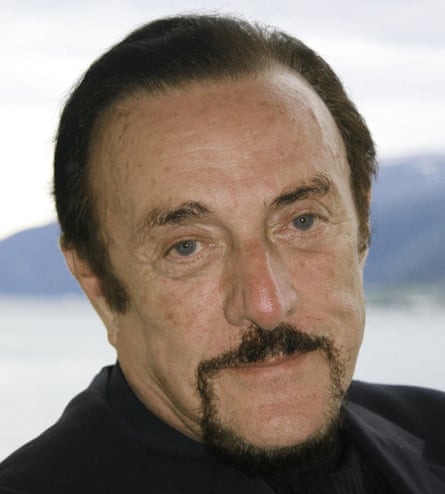

Why does any of this really matter, I ask the American psychologist Philip Zimbardo, who cites these figures in his new book Man (Dis)connected: How Technology Has Sabotaged What It Means To Be Male. Why do boys need fathers?

Zimbardo, professor emeritus at Stanford University, replies that everybody needs a mother and father because they give different kinds of love. “Mothers give love unconditionally – because you came out of her body, a mother loves you. You bring home your report card and it’s all Cs? Mom will say, ‘It’s OK. Momma loves you anyway. Try harder.’

“Fathers give love provisionally. If you want your allowance, if you don’t want me to turn off your computer, then you’ve got to perform. That’s always been the deal with fathers and sons – you don’t get a pass just because you exist, just because you got my name on your birth certificate. You’re going to do it because you want your father to love you and admire you. That central source of extrinsic motivation is gone now for almost one out of every two kids.”

The book, by Zimbardo and his co-author Nikita D Coulombe, is about why boys don’t man up as previous generations of males ostensibly did.

They argue that, while girls are increasingly succeeding in the real world, boys are retreating into cyberspace, seeking online the security and validation they can’t get anywhere else. They are bored at school, increasingly have no father figures to motivate them, don’t have the skills to form real romantic relationships, feel entitled to have things done for them (usually by their parents) and seek to avoid a looming adulthood of debt, unfulfilling work and other irksome responsibilities. As a result, they disappear into their bedrooms where, he argues, they risk becoming addicted to porn, video games and Ritalin.

No wonder, Zimbardo argues, popular culture teems with moodles (“man poodles”) or infantilised jerks (think: Jackass, Failure to Launch, Step Brothers, Hall Pass and The Hangover series), devoid of economic purpose, emotional intelligence, temperamentally unable to commit or take responsibility.

Zimbardo claims that a majority of African-American boys have been brought up in female-dominated households for generations. “Sixty, 70% grow up in a female world. I would trace a lot of that poor performance of black kids to not having a father present to make demands and not setting limits. This is now spilling out of the black community to the white community.”

In the US, about a third of boys are raised in absent-father homes, while in the UK about a quarter of children are raised by single mothers, triple what it was in 1971.

But hold on. Doesn’t the absence of fathers hit girls as much as boys? Apparently not.

“Men are opting out and women are opting in. Women are working harder at jobs, they’re working harder in school, and they are achieving – last year women had more of every single category of degree, even engineering. This is data from around the world. Now in many colleges there’s a big gap as boys are dropping out of school and college.”

Zimbardo estimates that there are, in Britain and the US, 5-10% more women than men at many colleges and universities. “So they’re going to have to have affirmative action for guys because obviously one reason you go to college is to find a guy.”

Why are boys more likely to retreat into cyberspace than girls? “Boys have never been self-reflective. Boys are focused on doing and acting, girls are more focused on being and feeling. The new video-game world encourages doing and acting and not really thinking. Video games are not so attractive to girls.”

And pornography? “The relative proportions are hard to come by. But for girls, it’s just boring. In general, sex has always been linked with romance for girls – much more than for boys. For boys it’s always been much more visual and physical. I presume boys masturbate much more than girls – there’s no good data on that.”

Zimbardo reckons that online pornography is much more appealing to boys than girls, in part because it eliminates narratives. “With the old pornography there were typically stories. There was a movie, like Deep Throat, and in the course of some interesting theme people were having sex. Now it’s only about physical sexual contact.”

Such material, he argues, is increasingly and disastrously a boy’s introduction to human sexuality. “It’s such a bad introduction because it eliminates romance and love. It’s only visual so you don’t realise what you’re missing – the touching, the kissing, the communication, the negotiation of boundaries. When you see 100,000 instances of it, it becomes the social norm. Every boy believes this is what women want, what girls want.”

Zimbardo contends that immersion in online technology means that boys never learn basic social communication skills, still less how to flirt, risk rejection or ask for a date. As a result, boys are hobbled by a new form of social shyness.

“It’s always been difficult for boys to talk to girls because you are never sure what they want or what their agenda is. And now without trying or practice it becomes more and more difficult. So it’s a reason to retreat into this virtual world.”

How all this maps on to the experience of boys who are gay is less clear – his and Coulombe’s book is overwhelmingly about the crisis for heterosexual boys.

“The one thing every boy or man fears from girls is being rejected. I don’t want you to kiss me, I don’t want sex, I don’t want you, I don’t want to date. That fear of rejection by women is eliminated in this virtual pornography world.”

There is, Zimbardo suggests, a new phrase to describe people, mostly male, who don’t need another physical person to satisfy their sexual needs – “sexual singularity”. In Japan, there is even a phrase for the kind of man no longer interested in real sex, soshoku danshi – or herbivorous men. Zimbardo’s fear is that herbivorous men are becoming a global phenomenon. He also fears that, thanks to how online pornography is becoming more interactive and immersive, real-life romantic relationships will become even less appealing.

“Pornography is being moved to the next level. You’ll put on 3D glasses and the woman or man will proposition you. And in some cases it’ll be interactive – you could say ‘Take off your clothes’. The idea of the film-maker of 3D virtual sex is to make it seem ever more real, just as video games are. Soon they’ll be able to put the face of the viewer on to the leading character. So you’ll be the man the woman wants to have sex with.”

But there is a grisly paradox, Zimbardo argues. Boys’ retreat into a putatively safe virtual world involves, in fact, a new kind of rejection. “In online porn, the men are incredibly well-endowed – they are paid precisely because they have those attributes. In addition, some of the men take penile injections so they can perform for half an hour non-stop. When you’re a 10 or 15-year-old kid, you say to yourself, ‘I will never, ever look like that or perform like that’.”

One reason porn is providing the introduction to human sexuality for boys, Zimbardo argues, is because of the dearth of meaningful sex education at school. A quarter of British pupils, his book claims, have no sex education.

Indeed, he argues that schools are increasingly ill-suited to boys’ needs – another reason for their retreat into cyberspace. In the US, he says, 90% of elementary school teachers are women, while in the UK one in five teachers is a man. “Female teachers can be wonderful but they model skills that girls are good at – fine motor tuning rather than big physical activity. They don’t like boys running around. And, with funding shortages, they’re eliminating gym classes so boys don’t have the time to do physical activity.” He cites schoolchildren being assigned to write diaries as a compositional task. “Boys don’t write diaries! The worst thing I can imagine giving a boy as a present is a diary.”

In such feminised schools, Zimbardo argues, boys are bored. “So they’re labelled as having attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and given drugs like Ritalin.” Boys, he estimates, are five to six times more likely to be diagnosed with ADHD. “These drugs are addictive, so you’ll be taking them for the rest of your life.” Which, he argues, suits the drug companies. “They’re big businesses so they are encouraging teachers to do diagnosis and encouraging kids to be sent to the medical staff to get the drugs.”

What can be done to reconnect boys with the real world? Zimbardo has lots of suggestions: more male teachers, more incentives for men to establish boys’ and men’s groups so that the former can get the masculine mentoring they otherwise lack, welfare reform to encourage fathers to remain in the family loop, crowdsourcing initiatives to fund video games that are less violent and require more co-operation, parents to talk to their sons about sex and relationships so they don’t take porn to represent real life.

My favourite suggestion is that boys learn to dance. “It’s the easiest thing in the world,” says the 82-year-old professor with the enthusiasm of an American Bruce Forsyth. “I would say if you’re a parent the most important thing you could teach your kid to do is social dancing. Because at a dance – I don’t even know if kids go to dances any more – you see girls dancing with each other. And if you were a boy and said to a girl, ‘Would you like to dance?’ you would be so popular. Most of the dance schools are for older people, but there should be dance schools for teens.”

If there were, boys might experience something they are increasingly less likely to as their lives become more and more virtual – what it is to touch and be touched by a real, live human being.

It’s a lovely dream, but one that Zimbardo doesn’t expect to be put into practice any time soon. In fact, he has little hope that any of the book’s suggestions will be realised.

“This thing with boys is really getting me down because I can’t think of a solution that is easy to entrain, that’s easy to realise. It’s painful for me because I’m an optimistic person. Boys are in a mess.”

As if to clinch the point, Zimbardo tells me about how he recently took part in a documentary about boys called The Mask You Live In. Directed by Jennifer Siebel Newsom, it’s a sequel to her film Miss Representation, about the false depictions of women in the media. In one scene, a US school teacher gives a group of boys each a circular piece of paper. On one side they write what their image is, and on the other what they are feeling. Then they scrunch up the paper and throw it to another kid. “What they said was all the same,” recalls Zimbardo. “On the outside it said: ‘Tough. Fearless. Kick your ass.’ And on the inside: ‘Lonely. Sad. Got no friends.’ Each boy was stunned that the others felt the same way. I think it’s what it’s like for boys now – they’re in a terrible state and I can’t imagine that it’s going to get better any time soon.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion