This post has been corrected.

When the Rana Plaza garment factory collapsed two years ago today and killed more than 1,130 people outside Dhaka, Bangladesh, a harsh global spotlight suddenly shone on the country’s garment industry, which had quietly been making more and more of the world’s cheap clothes for years.

That spotlight showed an industry in chaos, rife with horrifically unsafe conditions, corruption, shoddy oversight, low wages, and child labor. Apparel companies including the Walt Disney Company have reacted to such disasters by pulling their business out of Bangladesh. But that does nothing to improve the lives of workers there, many of whose livelihood, meager as it is, depends on the garment business.

As the Bangladeshi journalist Zafar Sobhan wrote after an earlier catastrophe, a fire at the Tazreen Fashions garment factory outside Dhaka that killed 112 workers in 2012, “it is this dehumanizing, soul-destroying, exploitative trade that has provided employment to over 3 million impoverished Bangladeshis, the vast majority of them women, and utterly transformed the economic and social landscape of the country. In the 40 years since independence, the poverty rate has plummeted from 80 percent down to less than 30 percent today, GDP growth has averaged around 5-6 percent for over 20 years, and the garment industry has had a lot to do with it.”

Indeed, many in the international development community refer to Bangladesh as a success story, having rightfully shed its “basket case” status to excel in areas such as gender equity and healthcare, and even to outshine its much richer neighbor, India. Bangladesh’s industrial revolution, supported in large part by garment manufacturing, is fueling a social one too.

But even those who applaud the societal change that Bangladesh’s garment industry has helped bring about acknowledge that the sector’s safety regulations and protections for garment workers remain nowhere near sufficient. The thing that makes Bangladesh’s garment industry so huge is the same thing that makes it dangerous—and difficult to fix.

It’s just so cheap.

A rapid rise

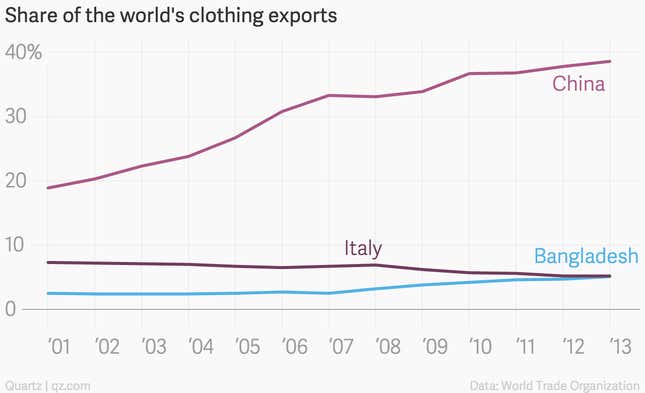

In the past decade, Bangladesh’s production share of the world’s cheap clothing has skyrocketed.

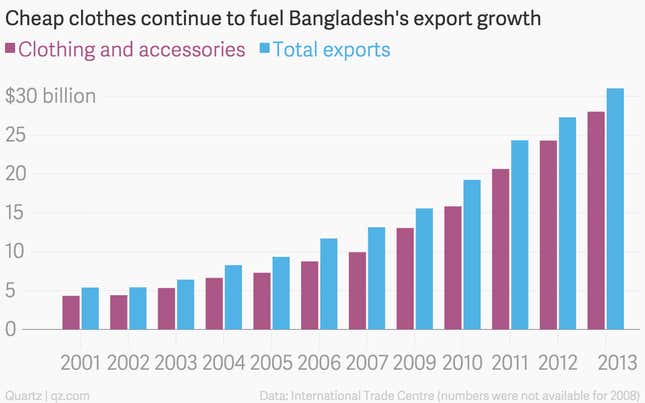

In 2013, Bangladesh exported nearly $31 billion of goods overall—nearly twice what it did just four years earlier in 2009—according to data from the International Trade Centre. About 90% of that value, some $28 billion, came from clothes. It is the world’s second-largest garment exporter, and its share of the global closet just keeps growing.

Cheaper than China

Bangladesh rose to its position largely because of its lack of regulation and the low wages it pays its garment workers, most of whom are women. Bangladesh’s minimum wage for the sector is one of the world’s lowest (pdf)—or according to some groups, the very lowest—even after the government raised it in response to fallout from the Rana Plaza disaster. As fashion brands look to cut costs, and wages continue to rise in China, Bangladesh becomes an increasingly attractive place to make clothes on the cheap.

A 2014 study done in collaboration with the United States Fashion Industry Association, for instance, found that half of the executives surveyed (pdf) said they expected to reduce sourcing from China in the next two years. At the same time, 60% of respondents expected to “somewhat increase” their sourcing in Bangladesh, and 5% expected to “strongly increase” sourcing in the country.

Lax regulations and lack of living wages

It can’t be denied that cheap labor and Bangladesh’s lax regulations—which own a large share of the blame for the Rana Plaza collapse—are part of Bangladesh’s draw. Sabina Dewan, executive director of the Just Jobs Network, says Bangladesh’s government has “very publicly” pitched its garment industry in that light as a way to attract investment.

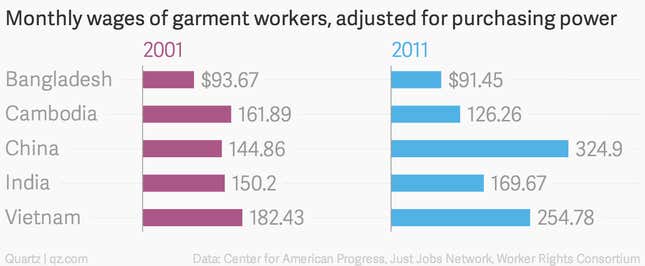

Her organization released a report just days before the Rana Plaza collapse looking at how real wages, which account for inflation and purchasing power, have changed in the garment sectors of various countries.

From 2001 to 2011, Bangladesh’s garment workers actually saw their incomes decrease in terms of purchasing power, while China’s wages more than doubled in the same terms. The drop occurred even though worker productivity increased in Bangladesh.

Equally troubling, the report found that the typical wage in Bangladesh was just 14% of a living wage that would provide for the basic needs of a worker’s family.

Although the data is from 2011, Dewan says nothing has changed significantly, even with post-Rana Plaza minimum wage raises.

Is this progress?

“As appalling as they are, these sweatshops are signs of a kind of advancement,” Zafar Sobhan explained. “In 2012, few Bangladeshi starve to death any more. This wasn’t the case a generation ago when 80 percent of the country subsisted on agriculture, survival being by no means guaranteed.”

Of course, as Sobhan points out, “burning to death is not an improvement over starving to death.” In the US, New York’s Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, which killed 146 workers in 1911, was a pivotal moment in establishing labor codes and safety measures for US workers. Rana Plaza, Tazreen Fashions, and the many other disasters that have killed thousands of Bangladeshi garment workers in the last decade could inspire a similar clarion call.

But will they? In the wake of the catastrophe at Rana Plaza, Western clothing brands formed groups to inspect factories and provide safety oversight—and some funding for improvements—to the factories they worked with. But regulating—or even finding—factories and subcontracting shops in the vast informal network that makes up Bangladesh’s garment industry has proved easier said than done.

It’s a quandary, and solving it will require cooperation among Bangladesh’s government, its private sector, its population, and the numerous foreign companies with an interest in keeping Bangladesh’s wages low.

Well-meaning Western shoppers have dubbed today, the anniversary of the Rana Plaza tragedy, “Fashion Revolution Day,” and are tweeting selfies to promote awareness of their clothing’s origins, and endorse ”ethical” sourcing. But as international brands increasingly depend upon Bangladesh’s garment industry to produce the clothes that fill our collective global closet, consumers are left with little clear direction on how best to effectively press for real change.

Correction (April 29, 2015): An earlier version of this post said the Walt Disney Company pulled its business out of Bangladesh in reaction to the Rana Plaza collapse. The company says it pulled its business a month prior to the disaster, in March of 2013.