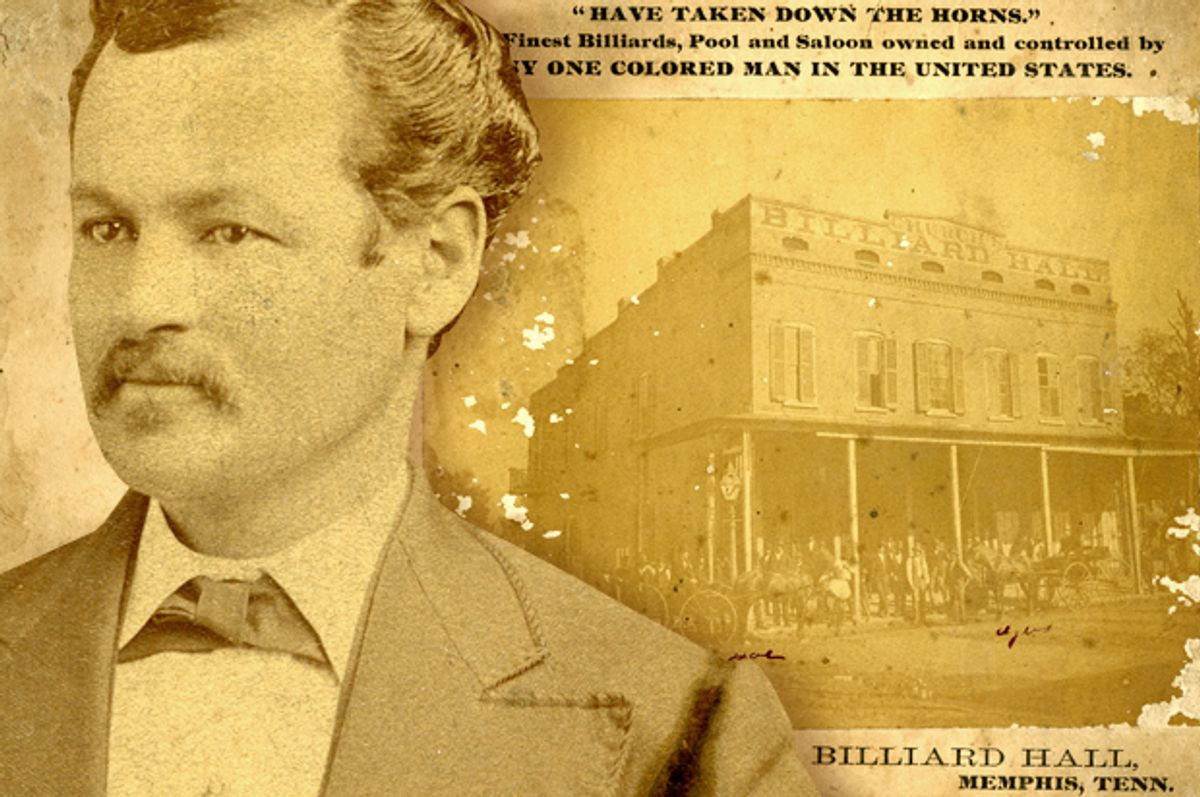

Depending on which critic or fan you ask, Fox TV’s "Empire" is somewhere between Shakespeare’s drama "King Lear" and Norman Lear's campy "Good Times." Less apparent to the show’s legions of viewers is how the story of Lucious Lyon and Empire Entertainment echoes the original black empire, a real-life dynasty of vice, virtue, and power, built in the heart of the old Confederacy just after the Civil War by a former slave who became monarch, Robert Church.

Like Lucious Lyon, who must plan for the future of his empire after being diagnosed with a crippling, often fatal, ailment, Bob Church had plenty of reasons to consider his legacy. It wasn’t so much that a specific death sentence loomed over Church—he just happened to find himself in life threatening situations, often. By his early 30s, Church had survived two gunshot wounds to his head, a steamboat disaster, a Civil War naval battle that he escaped by swimming the Mississippi River and an assassination attempt that backfired when a shotgun aimed at him exploded toward the shooter. Had Bob Church not been the combination of tough and lucky that saved him in these fateful scrapes, legendary Beale Street in Memphis, Tennessee, might be just another strip of concrete. Instead, it gained such an extraordinary reputation that Memphis entertainer Rufus Thomas would crack, “If you could be black on Beale Street one Saturday night, you’d never want to be white no more.”

Beale Street’s birth as an alternate universe for black America, a center of political clout and cultural fertility that changed America, all began with Church.

Again, a major similarity to Lucious Lyon—while Lucious financed his Empire with drug money before branching into music, Bob Church started off running saloons and pool halls. And just as a woman took the fall for Lucious when he hit it big, women took the fall for Church—he built his empire with brothels. Red-light district development was a daring scheme anyway, especially for a former slave, even more so because the staff were white. This, while black men around the South were lynched for looking at white women.

The Memphis underworld during the prim Victorian Age had a helpful ally who happened be the most powerful man in the city. White businessman David “Pappy” Hadden not only held Memphis’s top political office (“president” of the Shelby County taxing district during a Yellow Fever epidemic in 1878-9 when Memphis surrendered its city charter and abolished the office of mayor), he also presided over criminal court. When two beautiful blonde prostitutes were arrested for parading the streets on horseback, scantily clad, Pappy Hadden set the moral tone of the city in court. “You girls are probably ignorant of our rules here, but you won’t be in a moment, for I’ll state ’em: You must stay in the house at night. In the day time you can go ridin’ if you conduct yourself so people can’t tell you’re different from other ladies, but when you violate the rules, you must suffer the penalty of iniquity and divide the wages of sin with the city.” In other words, they weren’t fined for anything more than calling attention to themselves. Memphis as a whole was run on a “dividing the wages of sin” basis. Thus could a black man, with white customers and white support from the city’s highest offices, run the local sex trade.

A more lowdown, wide-open place could scarcely be imagined. In the spirit of Rufus Thomas’s remark about how one Saturday night on Beale could make a person change their color, a protégé of the Church dynasty spent 10 years collecting whorehouse rents for the boss and rolling dice in his gambling halls, before being exposed as a white man of prominent heritage.

But Bob Church too began dividing the wages of sin.

In 1886, an upstart black journalist named Ida B. Wells had reluctantly moved from Memphis, where she’d started a promising career in journalism, to a remote town in California where her family relocated and she took a teaching job. Wells yearned to be back on Beale, where she’d written for two of the local black-owned papers, and seen her byline picked up in similar sheets across the country. Her reputation as a crusader for her race was on the rise. Her life in California offered no such excitement or opportunity to make a difference. But she couldn’t afford the train fare back to Memphis.

She desperately turned to the one person she hoped could help. Wells scribbled in her diary, “Wrote a letter to Mr. C asking the loan of one hundred dollars.” She had never met Mr. C but “told him that I wrote to him because he was the only man of my race . . . who could lend me that much money and wait for me to repay it.”

In her newspaper writing, Wells had drawn attention to many of the issues facing her people, criticizing them for not being up to certain challenges. No one was safe from her pen. She had pointedly asked her readers to ponder, “What benefit is a ‘leader’ if he does not devote his time, talent, and wealth to the alleviation of his people’s poverty and misery and to their elevation?”

On her way to work the first Thursday of September 1886, Wells received an envelope: inside was a check from Bob Church for one hundred dollars. Mr. C had come through.

In Memphis again, Wells went to thank Church. She offered him collateral and said she’d repay his loan with interest. He refused. Toward the end of her long career, she recalled, “My gratitude for his kindly act and his trust in a girl he knew only by reputation warms my heart today when I think of it.”

Thanks to a little well-placed prodding from Wells, Church diverted dollars from his whorehouses into a range of more virtuous ventures. He built a park for black citizens that outshone anything white people segregated them from. He built the first black-owned bank, and he supported the arts—from piano pounders in lowdown saloons to upscale dance orchestras.

Understanding the uncertainty of the vice-lord life in a hell-roaring river town, Church knew he must cultivate an heir. His eldest son Thomas lived in New York, passing for white, some have said. Thomas wouldn’t do. Eldest daughter Mary had become a steadfast leader in her own right, the first black woman on Washington, D.C.’s board of education and a founder of the NAACP. She could not be compromised. As with Lucious Lyon’s three sons, there was some competition among the Church children—they all would have liked to keep his money—but unlike "Empire’s" twisted succession plot, old man Church had no doubt who to choose: his youngest son, Robert Jr.

In the beginning, Bob Church Jr. partnered with the heir to Pappy Hadden’s legacy, a man who gained great notoriety as a political-machine mastermind: “Boss” Ed Crump. The rise of Boss Crump and that of a landmark cultural contribution of Beale Street and the Church dynasty were intertwined, thanks to a black songwriter named W.C. Handy. Handy came to Beale as an orchestra and marching band leader, but became intoxicated with the raw music of Memphis. As a composer, he sampled the underground soundtrack of Beale saloons, red-light parlors and streetcorner poetry, quilting a new style together and, most importantly, publishing it in sheet music. His breakthrough hit began as a campaign tune for Mr. Crump and changed popular music as “Memphis Blues,” the sound of the world Bob Church made, a key cultural contribution of the Beale Street dynasty.

The dynasty saw its moment of greatest importance—and vulnerability—under Bob Church Jr.’s control. Unlike his father, the son aspired to a more public leadership role, and found his calling in politics. Fifty years before the civil rights movement swept the South, Church organized mass registration of black voters, beginning on Beale Street, and reaching across Tennessee before branching into border-states and the Midwest. Most shockingly, Church helped win Tennessee in the 1920 presidential election, for the then-liberal Republicans, the first time a former Confederate state had gone for the party of Lincoln since the 1870s. Imagine Alabama going Democrat today, to get a sense of this coup.

Afterwards, the party chair wrote to President-elect Warren Harding, “He is in a class by himself, in the colored race of this country, as to matters political. . . . the fact is that the one outstanding man out of all the colored people in the quality of unselfish and efficient work done is Robert R. Church. He goes about largely at his own expense on political errands, never taking a salary, and he is a very exceptional individual.”

Church established what one political writer of the day called a hotline from Beale Street to Pennsylvania Avenue. But his national prominence came at a cost to his local fortune. Church recognized that he could not run whorehouses as a black politician, and got out of the lucrative vice trade.

We’ll have to wait and see if Lucious’s heir takes Empire Entertainment in as bold a direction as Bob Church Jr. took the Beale Street dynasty. No matter what, Empire Entertainment should beware the lessons of the son, who found out that his chief assets and most damaging liabilities were the same, just as his mightiest allies were also his greatest rivals.

Shares