As the language of sports grows evermore entwined with analytics, new words and ideas are created from numbers. In baseball, ‘WAR’ (Wins Above Replacement) measures each player’s contributions to his team’s success based on data from each event on the field. In hockey, ‘Corsi’ uses shot attempts and shift data to measure how each player contributes to his team’s puck possession. These sports, as well as basketball and football, all have dozens of new concepts and acronyms inspired by ever-growing troves of statistical databases.

But in tennis, there have been few if any new words or ideas, because the numbers to inspire them have been invisible to the public.

Carl Bialik, a lead writer for ESPN’s data-driven FiveThirtyEight site, has often written about tennis – but not as often he might like to. Bialik, an avid tennis player himself, says that the sport’s unusually strong connection between watching and playing would make insightful analytics applicable to the recreational play of fans.

“I have various lists and documents that probably add up to a couple hundred stories in these different veins that are really just a wish list at this point,” said Bialik. “I don’t care if I write it or if someone else writes it; I just wish that, in general, tennis writers had access to better information, and that it was easier to answer those kinds of questions, even if they’re just the first question for a story that’s not primarily numbers driven.”

The most powerful data collecting in tennis comes from Hawk-Eye, the multi-camera visual tracking technology which was introduced to tennis for the purpose of reviewing line calls. Hawk-Eye technology tracks both the movement of the ball and the players, and the raw database generated would allow for a multitude of questions, including many of Bialik’s, to be answered.

“Is it better to chip an approach or drive an approach?” Bialik suggests. “Is it better to hit behind someone or in front of them? How do you do attacking Nadal’s forehand relative to attacking his backhand? How do players’ RPMs change over the course of a match? How does the speed of a shot affect the chance that the next shot will be an error? Just in that vein of really tactical questions that describe how the sport is played and perhaps how it should be played, there’s a lot that you can do.”

While sharing some of its insights with broadcasters for use during matches, Hawk-Eye has not opened up its massive trove of data to the public. Individual tournaments own the Hawk-Eye data from their events, but none of them have made it all available, either. With most tournaments ramping up for only a brief window of activity each year, and lacking significant year-round staff, long-range analytics facilitation are a low priority, if even on the radar at all.

The most Hawk-Eye data is generated at the BNP Paribas Open in Indian Wells, which has the technology installed on all of its match courts. Tournament director Steve Simon said there was “no reason to hide” the data, but said most of his tournament’s usage of the data would be to provide more enhancements for “second screen” experience for fans, be it on the tournament’s app or in on-site video displays.

Above the individual tournament level, data has been treated as something to monetize and profit from, rather than to share openly. Data at the Grand Slam events is branded by IBM, which focuses its most visible efforts into predictive calculations called “Keys to the Match”, theoretical goals players need to win reach to beat their opponent – for example, “Rafael Nadal needs to win 74% of points on his first serve”. The WTA has licensed its statistics to SAP, which has focused more of its efforts on displays for coaches to use, as well as some infographics that emphasize presentation over innovative insight. The ATP has much of its statistical analysis sponsored by FedEx.

Greg Sharko, director of media information for the ATP, said that the men’s tour is constantly looking for new metrics to add to their statistics leaderboards, but that opening up their raw database to the public was “something that we haven’t really thought about”.

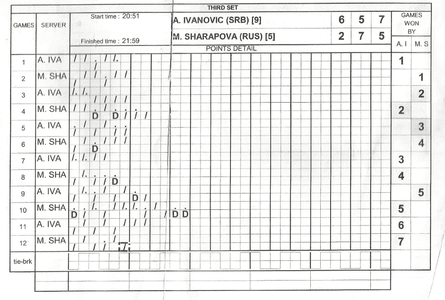

While Hawk-Eye provides the most dynamic data for select matches, even the most basic raw match data is not easily found. Scorecard data, which is generated by the chair umpire officiating each match, records in barebones fashion what just happened after each point: which player won the point, if there was a second serve, and if it was an ace or a double fault. Printed copies of these scorecards are available for each match in the media centers of tournaments, but they are not compiled or archived anywhere for the public use.

Jeff Sackmann, who has worked in baseball statistics and analytics for nearly a decade, has benefited from a tradition of record-keeping and open troves of data in that sport which date back more than a century. In tennis, however, he found nothing even remotely comparable.

“One of the big questions that researchers are asking in every sport are variations of the ‘hot hand’, of streakiness,” said Sackmann. “If you want to know if players are more likely to hit an ace just after they’ve just hit an ace, or are players more likely to break serve right after their serve has been broken. Any question that depends of one thing happening because another thing just happened, the scorecards would be huge for that.”

With no database of any kind available to start from, Sackmann started to build one himself. Trawling the websites of the ATP, WTA, ITF, and more with code used to extract and organize thousands of pages of draws and match statistics, he was able to slowly create his own compendium of data, the likes of which had never been uniformly compiled for public consumption. The project, which became his website Tennis Abstract, took two years to complete.

“The stuff is all public,” he said. “It’s just a matter of putting it all in one database so that it takes a couple of hours to get started instead of a couple of years to get started.”

To save others from having to travail similarly, Sackmann has published massive caches of data this month onto his blog Heavy Topspin, including rankings and results archives, point-by-point data from the last four years of Grand Slam events, and the raw data from over 700 matches which he and volunteers have fastidiously recorded shot-by-shot over the last two years for his Match Charting Project.

The paucity of data has made the analytical community of tennis similarly malnourished. When Sackmann was invited to speak at the Sloan Sports Analytics Conference in February, he was the sole representative of the sport.

“It was pretty lonely,” he said. “I met a few interesting people who were interested in tennis, but it’s a tiny, tiny fraction compared to the big sports, as you might imagine.”

Because tennis is controlled by several organizations instead of one unified umbrella league like most major sports, Sackmann believes such crowdsourced initiatives are the best bet for changing the face of tennis analytics, and that much of the reason for the statistical stagnation in tennis comes from simple lack of necessity from the sport’s stakeholders.

“The people who will pay for stats, the people who will drive analytics forward, are the ones who need to make multimillion dollar decisions,” he said. “If you’re the general manager of the Yankees, it’s worth millions of dollars to know if you should draft this player, or trade for this player. You need to know how much each individual player is worth on a team. That’s what a lot of analytics are about. If the Yankees won 100 games this year, how much of that can we credit to the shortstop or the center fielder or the closer?

“Whereas in tennis, if Roger Federer wins a match, you can credit 100% of that to Roger Federer, right? You don’t need somebody with a spreadsheet to tell whether that’s 70% Roger and 30% [Federer’s coach] Severin Luthi. So there’s not really demand for it.”

Without access to numbers to prove or disprove potentially incorrect notions, tennis coaches, analysts, players and journalists have had to rely more on established adages than actual evidence.

“I’m not saying this to be critical of tennis commentators, but listen to them talk for an hour and you’ll hear so many unproven assertions that the whole tennis world has taken for granted,” he said. “Maybe they’re right; I’m sure some of them are correct. Our perception that players are more likely to break after they’ve been broken, things like that. But we don’t have the proof. No one has ever looked into these things, because the data has made it so hard to do so.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion